As such, the FSR looks at questions like do Indian banks (both public and private) have enough capital to run their operations? Are the levels of bad loans (or non-performing assets) within manageable limits? Are different sectors of the economy able to get credit (or new loans) for economic activity such as starting a new business or buying a new house or car?

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

While trying to answer such questions, the FSR puts together a wealth of data and information that also allows the RBI to assess the state of the domestic economy, especially in a fast-changing global economy. Equally importantly, the FSR also allows the RBI to assess the macro-financial risks in the economy. Macro-financial risks refer to the risks that originate from the financial system but affect the wider economy as well as risks to the financial system that originate in the wider economy.

For instance, if a high percentage of loans extended by banks in the past turn “bad” (that is, they are not being repaid) — perhaps because of a lockdown or fall in demand for certain goods and services — then such banks will be unable to extend new loans to the wider economy because their profitability would have been eroded. So what starts as a bad loans problem for banks could turn into a massive roadblock for the growth of the rest of the economy.

Similarly, the RBI tries to understand how a shock in one part of the financial system — say the banks — is affecting another part of the system — say the companies that finance housing loans.

Story continues below this ad

As part of the FSR, the RBI also conducts “stress tests” to figure out what might happen to the health of the banking system if the broader economy worsens. Similarly, it also tries to assess how factors outside India — say the crude oil prices or the interest rates prevailing in other countries — might affect the domestic economy.

Each FSR also contains the results of something called the Systemic Risk Surveys.

Each FSR also contains the results of something called the Systemic Risk Surveys.

ExplainSpeaking has written about the last two FSR here and here.

A year ago, as India was still wrestling with the first Covid wave, the RBI was most worried about bad loans shooting through the roof. According to the FSR in June last year, depending on the level of stress in the economy, Gross NPAs could rise from 8.5% (of gross loans and advances) at the end of March 2020 to a two-decade high of as much 14.7% by March 2021.

Story continues below this ad

A year later, the FSR has found that the actual level of bad loans as of March 2021 is just 7.5%. However, the FSR is quick to point out that “macro-stress tests” for credit risk show that the GNPA ratio of Scheduled Commercial Banks “may increase from 7.48 per cent in March 2021 to 9.80 per cent by March 2022 under the baseline scenario and to 11.22 per cent under a severe stress scenario”.

In other words, while relief provided by the RBI in the past year — cheap credit, moratoriums and facilities to restructure existing loans — has contained the number of Indian firms that openly defaulted on their loan repayment, things could yet get worse, especially for the small firms (or MSMEs).

It all depends on factors such as the evolution of the virus (and its impact on the economy) as well as the decision of central banks the world over (especially the RBI) to raise interest rates (to contain rising inflation) and wind up their cheap money policy.

In fact, and even Governor Shaktikanta Das observes this in his foreword, a clear picture of NPAs will emerge only when the regulatory relief provided by the RBI is taken away.

Story continues below this ad

But it is not always clear when a central bank should pull back such regulatory relief.

The FSR explains the quandary: “Historical experience shows that credit losses remain elevated for several years after recessions end. Indeed, in EMEs [Emerging Market Economies], non-performing assets typically peak six to eight quarters after the onset of a severe recession. Eventually, support measures will be phased out. The longer that blanket support is continued, the higher the risk that it props up persistently unprofitable firms (‘zombies’), with adverse consequences for future economic growth”.

In other words, providing excess regulatory relief might just help firms that don’t deserve to get it because they are inherently inefficient. Moreover, helping out inefficient firms in this way is eventually a burden on the taxpayers of the country.

But there is a flip side too.

“If support measures are phased out before firms’ cash flows recover, however, banks will have to increase provisions and might tighten lending standards to preserve capital which might, in turn, undermine the recovery. Banks need sufficient buffers to absorb losses along the entire path to full recovery,” states the FSR.

Story continues below this ad

Beyond the NPAs, which have been the main concern for the RBI over the past year, the latest FSR also provides some key pointers to the state of the economy.

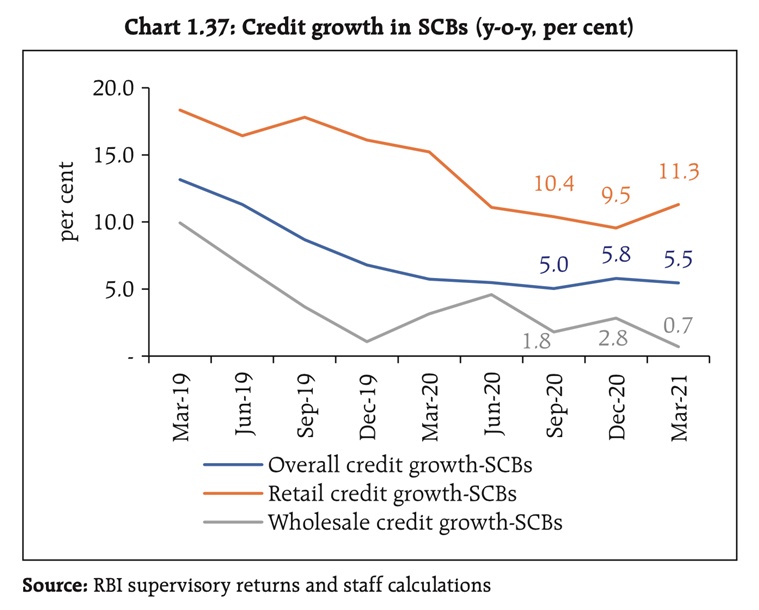

For instance, look at the chart below which shows the rate of credit growth in commercial banks. Three things stand out.

Rate of credit growth in commercial banks

Rate of credit growth in commercial banks

One, at less than 6%, the overall rate of credit growth (blue line) is quite dismal.

What is particularly worrisome is the negligible growth rate in wholesale credit (grey line). Wholesale credit refers to loans worth Rs 5 crore or more. The rate of growth for retail loans ( that is loans to individuals including housing loans, consumption loans for the purchase of durables, auto loans, credit cards and educational loans) had become much better in comparison.

Story continues below this ad

Thirdly, looking at the blue line, it is obvious how the sharp fall in credit growth happened much before the Covid pandemic hit India. This points to a considerable weakness in demand even before the pandemic and, in turn, suggests that recovery in credit growth may take longer than usual because the Indian economy had lost its growth momentum long before Covid.

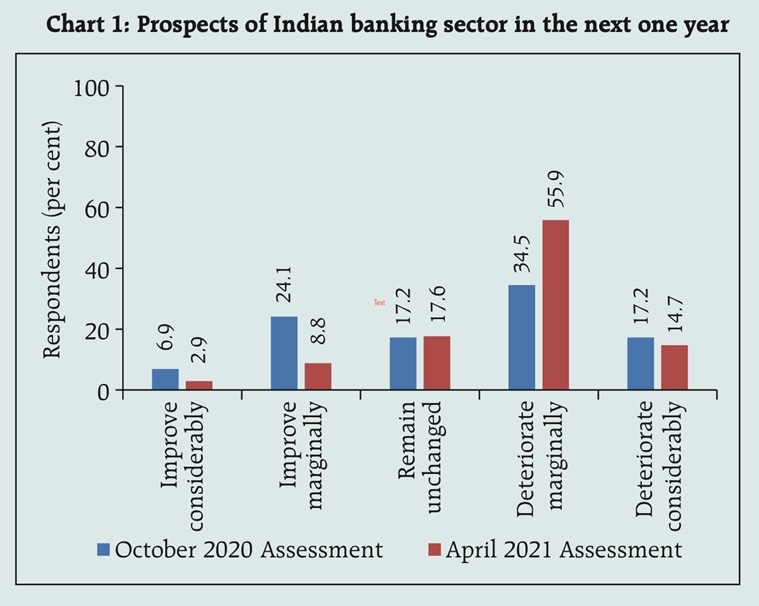

Beyond the data crunching, the FSR also published the results of the latest round (April 2021) of the Systemic Risk Survey (SRS), which looks ahead and tries to capture the perceptions of experts, including market participants, on the major risks faced by the Indian financial system. The risks are broadly classified into five categories namely global, macroeconomic, financial market, institutional and general.

Again, while the overall risk perception is “medium”, there were several factors on which experts expected a bleaker picture than the one provided in the January FSR — possibly because the SRS was done in April when the second wave had already started gripping the country.

The chart below maps the prospects of the Indian banking sector in the next year. More than 70% of the respondents felt the prospects would worsen.

Story continues below this ad

Prospects of the Indian banking sector in the next year

Prospects of the Indian banking sector in the next year

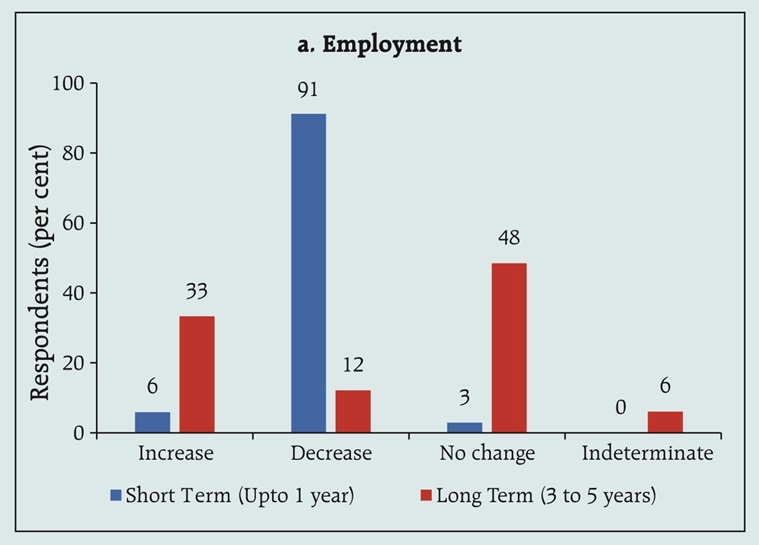

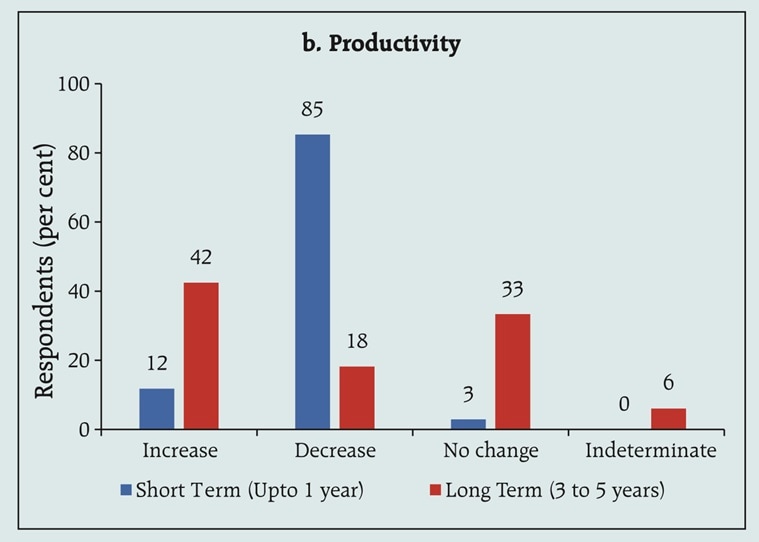

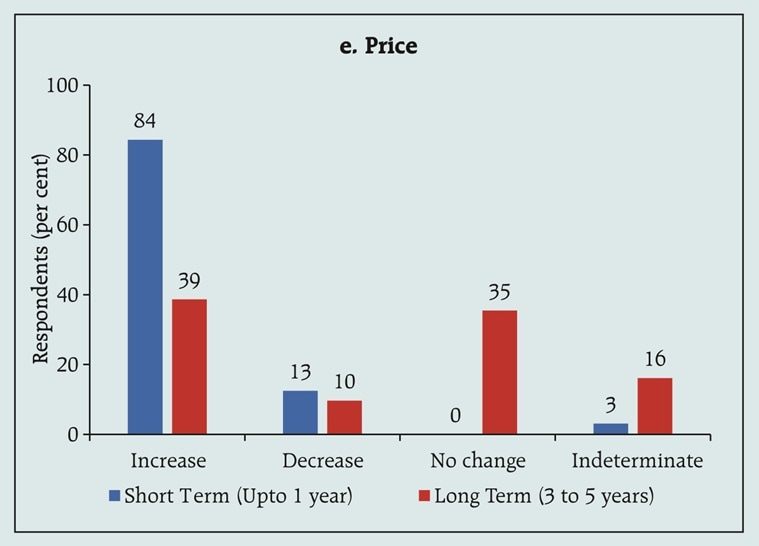

As regards the immediate impact (see blue-coloured bars) of the second Covid wave on the economy, an overwhelmingly large percentage of respondents expected employment, productivity, and wages to decline, even as they expected prices to rise. (See charts below)

Large percentage of respondents expected employment

Large percentage of respondents expected employment

Large percentage of respondents expected productivity

Large percentage of respondents expected productivity

Large percentage of respondents expected wages to decline

Large percentage of respondents expected wages to decline

Large percentage of respondents prices to rise

Large percentage of respondents prices to rise

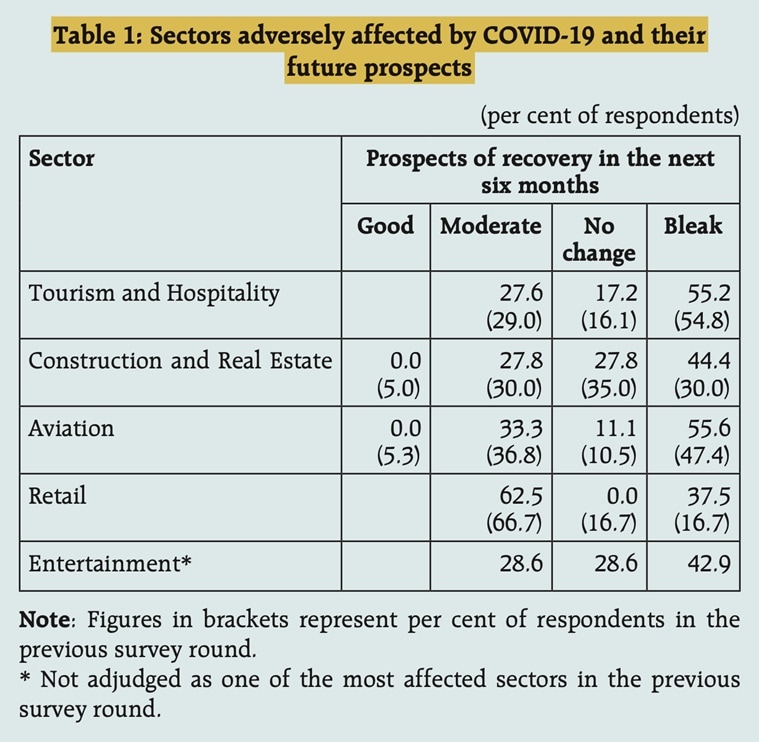

The table below names the sectors with the bleakest prospects in the first half of this year.

The table names the sectors with the bleakest prospects in the first half of this year.

The table names the sectors with the bleakest prospects in the first half of this year.

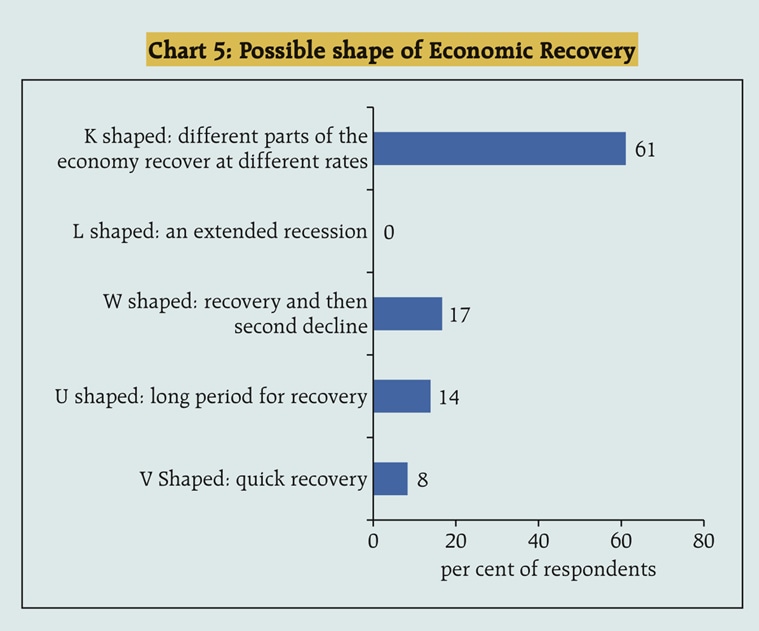

Of course, not everyone or every sector will recover at the same pace. As the chart below shows, most experts expect a K-shaped recovery from the second Covid wave. It is noteworthy that only a paltry 8% expect a “V-shaped” recovery.

Most experts expect a K-shaped recovery from the second Covid wave

Most experts expect a K-shaped recovery from the second Covid wave

Share your views and queries on udit.misra@expressindia.com

And stay safe,

Udit

Rate of credit growth in commercial banks

Rate of credit growth in commercial banks Prospects of the Indian banking sector in the next year

Prospects of the Indian banking sector in the next year Large percentage of respondents expected employment

Large percentage of respondents expected employment Large percentage of respondents expected productivity

Large percentage of respondents expected productivity Large percentage of respondents expected wages to decline

Large percentage of respondents expected wages to decline Large percentage of respondents prices to rise

Large percentage of respondents prices to rise The table names the sectors with the bleakest prospects in the first half of this year.

The table names the sectors with the bleakest prospects in the first half of this year. Most experts expect a K-shaped recovery from the second Covid wave

Most experts expect a K-shaped recovery from the second Covid wave