By the narrowest possible margin — 7-6 — a 13-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court ruled that the “basic structure” of the Constitution is inviolable, and cannot be amended by Parliament.

Kesavananda Bharati case

The extent of Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution was the backdrop of the tussle between the executive and the judiciary in the first two decades of the republic. In its judgments in the first string of cases, the Supreme Court viewed the power to amend the Constitution as unfettered, but that view changed subsequently.

In I C Golaknath & Ors vs State Of Punjab & Anrs (Feb 27, 1967), the Supreme Court reversed its earlier verdicts and ruled that Parliament cannot amend the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Parliament responded by amending the Constitution to give itself the power to amend any part of the Constitution — and passed a law that it cannot be reviewed by the courts. This scope of the power to amend — especially when the right to property (which was a fundamental right at the time) was impacted by the land ceiling laws — was the central challenge in the Kesavananda case.

In its majority ruling, the court held that fundamental rights cannot be taken away by amending them. It said that Parliament had vast powers to amend the Constitution, and upheld the land ceiling laws — but it drew the line by observing that certain parts are so inherent and intrinsic to the Constitution that even Parliament cannot touch it. The court ruled that in spirit, the amendment would not violate the “basic structure” of the Constitution.

Strong opinions and drama

The 68-day hearing is perhaps the longest in the history of the Supreme Court. Several commentators have noted that from the beginning, the 13-judge Bench, also the largest so far, was sharply divided. Justice P Jaganmohan Reddy, one of the seven judges who would form the majority, recalled the acrimony in his autobiography, The Judiciary I Served. He cited instances of his colleagues answering questions that were put to counsel by judges on the ‘other’ side.

Story continues below this ad

The late T R Andhyarujina, a former Solicitor General of India who was jurist H M Seervai’s junior on the case, recalled in his book an incident when Justice S N Dwivedi, one of the six judges who would later form the minority, spoke in a way that was perceived to be pro-government.

“Are you prepared to say that the fundamental right to property can be amended? If so, I am prepared to procure from Parliament that all other fundamental rights can be left unamended,” Justice Dwivedi asked Nani Palkhivala, who was arguing for the petitioners. (Kesavananda Bharati Case: The Untold Story of Struggle for Supremacy by Supreme Court and Parliament)

The hearing began in early October 1972 and went on until March 1973, with breaks for New Year’s and Holi. Justice M H Beg fell ill and was hospitalised twice during the hearing, which added to the delay. The fact that then Chief Justice of India S M Sikri was due to retire on April 25, 1973, added to the pressure of closing the hearing fast.

Tensions ran high among the lawyers, even among those who were on the same side. Then Attorney General for India Niren De, who would appear for the Centre, had lost a string of cases on the right to property issue. The government wanted Seervai to argue — according to Andhyarujina’s account, Seervai agreed on the condition that he would lead the arguments instead of the AG.

Story continues below this ad

When arguments began, De occupied the first seat, and showed no indication of giving up his right for Seervai. Palkhivala had opened the arguments for the petitioners, which went on for about 30 days. Eventually, De told the court that since he would be busy at a conference overseas, Seervai would open the arguments for the government.

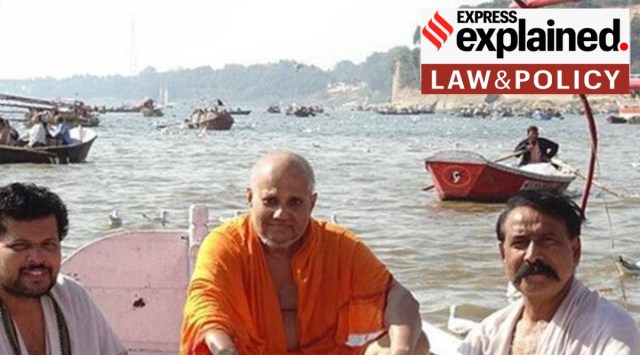

Seervai, who was briefed by the State of Kerala, opposed His Holiness Sri Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalavaru, the lead petitioner who lent his name to the title of the case. Kesavananda Bharati had been the head seer of the Edneer Mutt in Kerala’s Kasaragod district since 1961.

An aborted case review

In 1975, two years after the Kesavananda Bharati ruling, the Supreme Court sought to reconsider the verdict. On November 10, 1975, a 13-judge Bench, headed by then Chief Justice of India A N Ray, sat to review the “correctness of the basic structure doctrine”. The country was four-and-a-half months into Indira Gandhi’s Emergency at the time.

That same day — November 10, 1975 — a five judge Bench of the Supreme Court had delivered its judgment in the Indira Gandhi v Raj Narain case, popularly known as the Election Case, affirming the principles laid down in the Kesavananda ruling. The five judges on this Bench were also part of the Bench constituted to hear the Kesavananda review.

Story continues below this ad

For more than two days, the 13-judge Bench heard arguments from Palkhivala, who had represented the petitioners in Kesavananda. However, no judicial record of this review hearing exists, because it was abandoned midway. Fali Nariman referred to this as a “non-case”, and the constitutional historian Granville Austin wrote that this moment marked a definite assertion of the judiciary against the majoritarian Parliament of the time. (Working a Democratic Constitution: A History of the Indian Experience)

In his book Constitutional Law of India, Seervai, who appeared for the government in the Kesavananda case, wrote about the so-called attempt to review the basic structure doctrine. “Arguments were hurt for two days, but on 12 November 1975, as soon as the court assembled, Chief Justice Ray informed the parties that the Bench had been dissolved,” Seervai wrote.

“The sequence of events would suggest that Chief Justice Ray realised, before 10 November 1975, that his brother judges in the Election case were not likely to depart from the theory of the basic structure, and it would also suggest that the two days’ hearing before the Bench of 13 judges, satisfied him that the doctrine of the basic structure would not be considered by the present Bench,” Seervai said.