Expert Explains: As crucial Congress begins in China, a guide to the CCP’s structure and what to expect from meeting

The weeklong 20th National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party is widely expected to extend Xi Jinping’s paramount leadership. But there are factions within the party — here’s who might remain powerful and who might make way for others

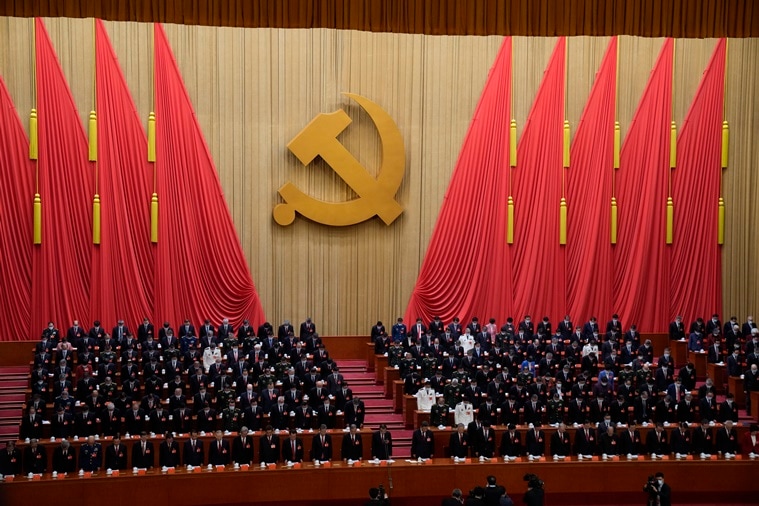

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a speech during the opening ceremony of the 20th National Congress of China's ruling Communist Party, in Beijing on Sunday. (Photo: AP)

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a speech during the opening ceremony of the 20th National Congress of China's ruling Communist Party, in Beijing on Sunday. (Photo: AP)The weeklong National Congress of the Communist Party of China began in Beijing on Sunday (October 16). This five-year event defines the political-institutional character of the CCP due to its monopoly of Chinese politics. Against the backdrop of a complicated and chaotic international situation — post-pandemic slow global economic recovery, and the Ukraine-Russia conflict — this 20th session of the Party Congress has acquired more significance than usual for both China and the world.

CCP internal structures and norms

About 2,300 party delegates have gathered in Beijing for the Congress. On its agenda is the selection of a new Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. The topmost members of the CCP constitute the Central Committee. The current Central Committee has 205 full members and 171 alternate members (to fill vacancies in case of death).

Out of these, 25 members, headed by the general secretary (President Xi Jinping holds this post), make up the Politburo (PB). Power is further centralised in a seven-member Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), which oversees all significant policies, decisions and agreements.

The Politburo is an amaranthine entity, with new members of the PB and PSC chosen by internal consultations between active Politburo members and retiring PSC members. The National Congress formally “elects” pre-selected members every five years. Politburo members also have concurrent positions in the government and influential regional offices and have authority over bureaucratic appointments.

According to the qishang baxia, or the “seven up, eight down” convention that has been followed since 2002, a person cannot be reappointed at age 68 years or older, and cannot be retired at age 67 or younger. New PSC members are mainly from the larger PB of 25, where the mandatory retirement age is 68.

Additionally, an interim rule published in 2006 mandates that officials should not hold a single job for more than two consecutive five-year terms. These norms do not apply to Xi Jinping, who is 69 years old and is being treated as the general secretary rather than an ordinary PSC member. Also, there is no mandatory retirement age in any CCP official regulation or document.

The composition of the top leadership in crucial decision-making bodies will demonstrate the political influence Xi and his allies wield, and how much support the president enjoys for certain viewpoints, such as a preference for stronger state intervention in the economy.

The factions within the CCP

Not surprisingly, for a party with an all-powerful leader, the CCP is a warring ground of factions supporting different perspectives, issues, approaches and regions. The leading group is headed by Xi Jinping, representing the “elitist coalition” or “princelings”. Many members are princelings, the offspring of revolutionaries.

A faction frequently referred to as the “Shanghai Gang” (led by Jiang Zemin and Zeng Qinghong) remains influential and is distinguished by its members’ propensity to represent the urban business interests of coastal regions. In his final round of anti-corruption purges, Xi has ensured that his hold over opponents strengthens. Sun Lijun, the former Chinese security vice-minister, and Fu Zhenhua, the former justice minister representing the Shanghai faction, have been put behind bars in this purge.

Attendees bow their heads to observe a moment of silence for fallen comrades during the opening ceremony of the 20th National Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party. (Photo: AP)

Attendees bow their heads to observe a moment of silence for fallen comrades during the opening ceremony of the 20th National Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party. (Photo: AP)

Yet another group is led by Hu Jintao, comprising members with a Communist Youth League background, sometimes called “tuanpai” or a league faction commonly referred to as the “populists”. With Xi coming to power in 2012, the princelings have come to hold an upper hand in the CCP.

Until the 19th Party Congress, the candidate’s age and work history allowed for predicting promotions in party leadership. However, with the 19th Party Congress, it became clear that devotion to President Xi Jinping has become the supreme quality desired for such promotion.

If age norms are strictly adhered to as they have been over the last two decades, four PSC members — Li Keqiang (67), Wang Yang (67), Wang Huning (67), and Zhao Leji (65) — should continue serving in this all-powerful body. Li Zhanshu (72) and Han Zheng (68) should retire, freeing up two PSC positions.

Hu Chunhua (59) and Chen Min’er (62) are the two most qualified PB members, given their equations with different factions. Liu He, another member of the current PB who heads the central government’s financial stability committee, is also a frontrunner for the PSC.

The question is, will Xi increase the numbers in the PSC to accommodate more of his own? There have been two experiments with the PSC membership in the past: in 2002, the membership was increased from seven positions to nine. In 2012, it decreased from nine to seven.

Xi is likely to preserve the norm-based composition of PSC rather than trigger any significant upheaval. A status quo of seven members is expected to be retained at this Party Congress even though that would mean that half of the PSC would be made up of tuanpai (Wang Yang, Li Keqiang, and Hu), with only two apparent Xi allies (Zhao and Chen).

Attendees gather before a press conference held on the eve of the opening session of the 20th National Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party in Beijing. (Photo: AP)

Attendees gather before a press conference held on the eve of the opening session of the 20th National Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party in Beijing. (Photo: AP)

Xi’s consolidation of power

If Xi follows a norm-based composition of the PSC, it would also represent a limit to his personal power at a time when he faces an ailing economy, antagonistic relations with the United States, and a strict zero-covid policy that further isolates China.

Of the potential seven members of the PSC, Wang Yang, Li Keqiang, Hu, and Chen have a pro-market reform orientation. The amplification of their voices is possible only if many technocrats enter the broader Central Committee.

But Xi’s hold on the party is unlikely to loosen. Political stability remains the keyword, given the deteriorating economic situation combined with the pandemic. So, the trend of supreme leadership over collective leadership will likely follow for another term, with a well-publicised Xi centrality.

Xi is all set to win a historic third term as the party’s secretary general. This will effectively allow him to remain in power for life, given that China’s leaders voted in 2018 to remove the two-term limit since the 1990s.

The party has been working overtime to highlight Xi’s legacy and leadership status to establish him at par with the party elders Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. It is anticipated that some of Xi’s initiatives will be adopted into the CCP constitution at the end of the Congress.

Five years ago, one set of his ideas had already been incorporated into the constitution. The “China’s Dynamic Decade” series is now airing on the state-run China Daily newspaper. In addition, the People’s Daily newspaper, Xinhua news agency, and state broadcaster CCTV have started a new series called “Navigating China that celebrates the advancement and policy achievements made under Xi’s direction”.

Security personnel on Tiananmen Square in front of the Great Hall of the People where the 20th National Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party is being held. (Photo: AP)

Security personnel on Tiananmen Square in front of the Great Hall of the People where the 20th National Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party is being held. (Photo: AP)

The other big appointments

Li Keqiang has declined to serve another term as the State Council’s premier, allowing Xi to appoint a close ally as the next premier, even though none of Xi’s PB allies has the pre-requisite experience.

Given his efficient administrative capabilities, Hu Chunhua, one of the two possible replacement choices in the PSC, is a contender for the premiership. Yet, Xi may prefer the elderly Wang over Hu.

In such a scenario, the two new members, Hu and Chen, may be marked as the future leaders for 2027-28. However, Xi may prefer to keep a door open for a fourth term, in which case the party is unlikely to resolve the succession issue at the 20th National Congress, in all likelihood causing a team of potential successors as rivals to emerge.

The Congress also presents an opportunity for Xi to appoint his trusted allies in three other critical power centres of the party — the military, the propaganda wing, and internal security. These moves will consolidate power in his hands. Perhaps he will follow the popular Chinese phrase, “bùzuò bùsǐ”, “if you don’t court trouble, you will not die!”

Delegates attend a preparatory meeting ahead of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. (Photo: Xinhua via AP)

Delegates attend a preparatory meeting ahead of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. (Photo: Xinhua via AP)

Takeaways for the region and the world

Yang Jiechi, the director of the party’s central committee foreign affairs office, is widely expected to retire. Liu Jieyi and Wang Yi are the two likely candidates for this post. Of the two, Wang Yi supports a tougher foreign policy. Liu Jieyi, on the other hand, is seen as close to the agendas of global governance reform and deterring Taiwan’s independence.

Irrespective of either’s entry into the PSC, Xi’s “Great Power Diplomacy” has made other existing bodies lose some importance. China has been pushing Xi’s economic, political, digital, and security models through the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative), GDI (Global Development Initiative), GDSI (Global Data Security Initiative), and GSI (Global Security Initiative).

The US-China trade wars will continue under Xi Jinping, as do the issues responsible for it: US’s export restrictions on China, its ban on Huawei and other Chinese companies working on 5G technology, such as ZTE, and the supply chain issues arising in the wake of the pandemic. While China’s reputation has suffered in the West, growing middle powers and smaller countries see China as their main hope for economic recovery. In the coming term, domestic issues are most likely to take precedence.

Rityusha Mani Tiwary teaches political science at Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi, and is an Honorary Fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05