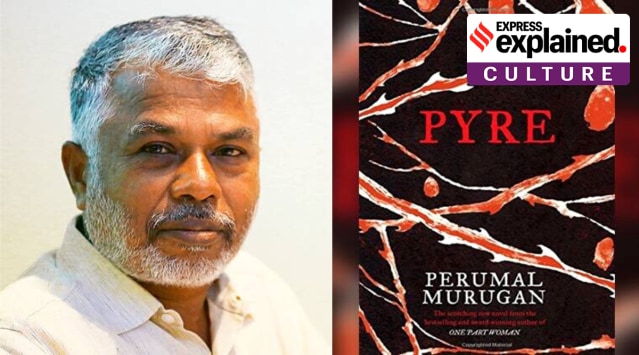

Tamil writer Perumal Murugan’s novel ‘Pookkuzhi’, translated as ‘Pyre’ in English by Anirudh Vasudevan, has made it to the International Booker Prize 2023 longlist, becoming the first Tamil novel to be nominated for the Bookers. The list was announced earlier this week on March 14.

In total, 13 novels have made it to the longlist this year. Apart from Tamil, Bulgarian and Catalan languages have made their debut this year. ‘Time Shelter’ by Georgi Gospodinov is the Bulgarian novel, translated by Angela Rodel, while Eva Baltasar’s ‘Boulder’ is the Catalan representation, translated by Julia Sanches.

The prize, worth £50,000 (Rs 50 lakh), is awarded annually for a novel or short story collection written in any language, translated into English and published in the UK or Ireland. The prize money is split equally between the author and translator of the winning book. The shortlist of six books will be announced on April 18 and the winner on May 23.

Who is Perumal Murugan?

Murugan is a novelist and professor of Tamil literature, who has written 10 novels (many of which have been translated into English), five collections each of short stories and poems and 10 non-fiction books relating to language and literature, in addition to editing several fiction and non-fiction anthologies. He has also written a memoir titled ‘Nizhal Mutrattu Ninaivugal’ (2013).

His work chronicles the everyday lives of Tamil rural folk, their traditions and social hierarchies. In particular, several of his books critique the caste system and how it operates through oppression and violence, such as his third novel, ‘Koolamadari’ (2000), translated into English as ‘Seasons of the Palm’ (2004) by V Geetha. It dealt with bonded labour and exploitation of so-called ‘lower-caste’ people by the so-called ‘upper-castes’.

Apart from fiction, his scholarly work has focused on the literature of the Kongu Nadu region, which comprises parts of western Tamil Nadu, southeastern Karnataka and eastern Kerala. Most notably, he has done extensive research on Kongu folklore, especially the ballads on Annamar Sami – a pair of folk deities. His documentation efforts have also extended to republishing various Kongu literature texts.

Story continues below this ad

He has also collaborated with Carnatic musician T M Krishna. Murugan wrote a poem for him on the topic of manual scavengers, an issue unheard of in the traditional Carnatic music sphere at the time.

Talking to The Indian Express, Murugan said, “Krishna asked me to write something about the community for him to sing. This took me about six months because I didn’t know which angle to approach this from, since this was an issue which was very much a part of the social consciousness. Eventually, I decided to go with ‘hands’ as the focus of the keerthanai, because hands were usually regarded as something with which to perform uyirvana vishayangal (higher tasks). How can the same hands be expected to lift excrement?”

The ‘Murugan is dead’ controversy

The nature of Murugan’s work has often invited backlash from conservative sections of society, including right-wing groups like the RSS. In a 2014 Facebook post, Murugan wrote, “Author Perumal Murugan is dead. He is no God. Hence, he will not be resurrected. Hereafter, only P Murugan, the teacher, will live.”

This came as a result of protests over his novel ‘Mathorubhagan’ (2010), translated into English as ‘One Part Woman’ by Vasudevan. The Kongu Vellala Gounder community, an influential intermediate caste in western Tamil Nadu, had in particular accused him of insulting their women and degrading a Hindu deity in the novel. Senior RSS ideologues also justified the attacks on Murugan.

Story continues below this ad

A ‘peace meeting’ brokered by the Namakkal district administration resulted in the Facebook post, as well as an agreement by Murugan to withdraw his novel. Another consequence of the protest was that Murugan was forced to leave his job as a professor at the Government Arts College in Namakkal, and relocate first to Chennai and then to Attur.

However, the Madras High Court in July 2016 ruled that the ‘peace meeting’ was illegal, and dismissed all criminal cases filed against the author by caste groups. “Let the author be resurrected to what he is best at. Write,” the court said. In 2017, ‘One Part Woman’ won the Sahitya Akademi’s Translation prize.

In an interview with The Indian Express, Murugan said he did not “fight back” as he didn’t know whom to testify against. “If the role of the state were to be looked at, I would say it had to prioritise law and order over anything else, as they do elsewhere. I didn’t take offence at the caste-communal groups either as I seriously doubt their concerns about God and faith,” he said.

Murugan added, “When my students planned protests, I asked them whether we should use the same language as they had used against my works. Once Buddha was asked why he was not reacting to repeated insults hurled at him by someone. He replied he hadn’t received those insults, so they remained in the possession of those who had hurled them.”

Story continues below this ad

Why is the longlisting significant?

The nomination comes at a time when Indian-language works are gaining more institutional recognition as well as popular favour through English translation. In 2022, Geetanjali Shree became the first Hindi novelist to win an International Booker for ‘Ret Samadhi’, translated into English as ‘Tomb of Sand’ by Daisy Rockwell.

Talking about ‘Pyre’ being longlisted, Murugan said, “This is the first time a Tamil novel has made it to the long list. It is very important for the language. It is significant not because it is my novel but because the selection is an acknowledgement of the literature in Tamil, in India.”

“English and Hindi are spoken as Indian languages whereas the others are classified as regional tongues. That is wrong. That sort of perception will change when books from our languages — southern languages as well as non-Hindi languages from the North — make it to international award lists,” he added.

Further, the very subject matter of Murugan’s work is noteworthy. The portrayal of caste and caste-based atrocities in art forms like literature, cinema, etc. to date invites backlash and censure, despite there emerging a bigger and more receptive audience for them in recent years. Cases of honour killing continually make the news. The longlisting of ‘Pyre’ assumes even more importance in this context.