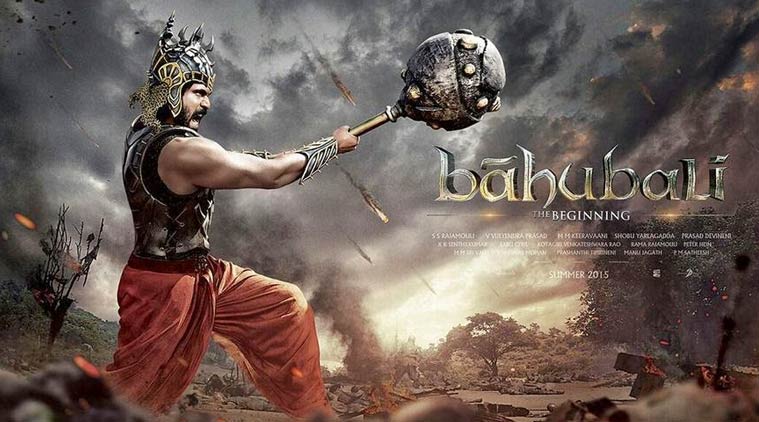

Opinion ‘Baahubali’ renews discourse on caste and films in Tamil Nadu

‘Baahubali’ underlines a trend in Tamil cinema: Of casteism subduing forces of equality.

‘Baahubali’ has set several new records, has proved that a film need not always require a superstar to become a blockbuster and has successfully blurred the line between southern cinema and Bollywood.

‘Baahubali’ has set several new records, has proved that a film need not always require a superstar to become a blockbuster and has successfully blurred the line between southern cinema and Bollywood.

The latest film to enter the discourse on caste and films in Tamil Nadu is Bahubali. The mention of “Pagadiyar Magan” (son of a Pagadiyar, purportedly a reference to a marginalised social community) drew violent protests in Madurai recently.

It began in the 1930s, with early Tamil pioneer K. Subramaniyam, a Brahmin, who sought to locate characters in the binary social divide between Brahmins and the “untouchables” in films such as Nandanar (1935). In this film, the Brahmin character, played by Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer, falls at the feet of the Nandanar, from an “untouchable” community, played by legendary female singer and actor K.B. Sundarambal, belonging to a “caste Hindu” community. It drew protests from Brahmins in places like Kumbakonam and there are references to the social boycott of Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer in Kumbakonam for the “sacrilegious act of falling at the feet of

an ‘untouchable’”.

In a land where casteist and religious conflicts have a centuries-old violence-soaked history, the advent of a communication culture mediated by Western imports, such as printing technology through the activities of Portuguese missionaries on the Tuticorin coast in the 16th century, resulted in a print culture that does not want to hide its casteist and religious rivalries four centuries on. The 19th century print culture of Tamil Nadu and colonial Madras had a well-oiled machinery that promoted such rivalries.

The ongoing social (casteist) contestations in Tamil Nadu express themselves through casteist swear words and these have echoes in the titles of Tamil films, in dialogues, in elements of the mise-en-scène, with roots in the casteist and religious rivalries that became a defining characteristic of the nearly 500-year-old print culture of Tamil Nadu and in the 2,000-year-old rivalry between the forces of hegemony and marginalisation.

From a purely Western, liberal, egalitarian and urbane perspective, the classical markers of modernisation have their basis in the knowledge revolution made possible by the printing machine and, later, by mass media like films, radio, TV and the new media of the internet and mobile phone. From a purely Indian perspective, these technological imports have created problematic print and film cultures wherein the Western, liberal and egalitarian logic that seems to pervade the media fails against the casteist and religious elements that lurk in the minds of not just producers, directors, actors, scriptwriters, etc, but also in sub-sets of the commercial film apparatus, such as fan clubs, actors’ associations, distributors, exhibitors, etc.

From a superficial perspective, the ongoing contestations are blamed either on the “lack of social awareness”, the lack of “social responsibility” and the “commercialism born of casteism” on the part of filmmakers or on the failure of the state and civil society to acknowledge the right of filmmakers to reflect their social realities. According to the latter view, what is part of social reality ought to find an expression in films and other media. However, the first axis of the binary warrants caution and accountability. What is being played out is the impossible state of acts of silence versus the expression of what is anyway a fact of social reality.

What is missing from such a perspective is the logic of failure of civil society against the forces of inequality. It is historical, in the sense that the struggle against the forces of class, caste and religion and the social failures they cause to marginalised sections was pioneered by the Buddha and several Tirthankaras in the Jain order, which flourished in Tamil Nadu. It is cultural, in the sense that the technologies of communication have to subsume their spirit of knowledge revolution in favour of the bipartite or tripartite logic of social contestations between and among Brahmins and non-Brahmins on the one hand, and between “caste Hindus” and Dalits on the other.

It was common in the Dravidian Cinema Era of the 1940s and 1950s to find cinematic versions of social contestations in the narrative duels between the “dominant” (fair skinned/ Brahmin/ upper class/ Aryan/ north Indian) and the “oppressed” (dark skinned/ Dravidian/ non-Brahmin). These films, however, did not exclude casteist markers of the non-Brahmin/ caste Hindu, since they deployed in good measure rich characters, drawn from caste Hindu communities, like the Mudaliars and Thevars, in the roles of zamindars set against characters drawn from the lower strata of society, but whose caste was not revealed. What was missing in these narratives was the binary widely prevalent in the current crop of Tamil films: Dalits vs caste Hindus.

The last three decades have seen a proliferation of Tamil films that do not seek to hide the fact that casteism continues to fail the forces of equality pioneered by the Buddha and the likes of Periyar and Ambedkar. In movies of this period, caste markers abound in the titles, as in Thevar Magan (1992), Chinna Gounder (1992); in dialogue, as in Bahubali (2015), Sundara Pandian (2012), Vamsam (2010), Bharathi Kannamma (1997), Vedham Pudhithu (1987); and in the contestations deployed through the cinematic instruments of editing, costume, lighting, etc, by taking advantage of the casteist markers of male and female bodies of the upper castes and the marginalised castes, as well as the socio-cultural rituals they embody.

The writer is professor at the department of journalism and communication, University of Madras.

(This article appeared in print under the headline ‘Caste in Film’)