Smallest microplastics present in ocean can be detected by fluorescent dye

A new research study has developed a fluorescent dye that can be used to detect microplastics in oceans.

The smallest microplastics in our oceans – which go largely undetected and are potentially harmful – could be more effectively identified using an innovative and inexpensive method developed by researchers. Scientists at the University of Warwick in the UK have developed a pioneering way to detect the smaller fraction of microplastics – many as small as 20 micrometres (comparable to the width of a human hair or wool fibre) – using a fluorescent dye.

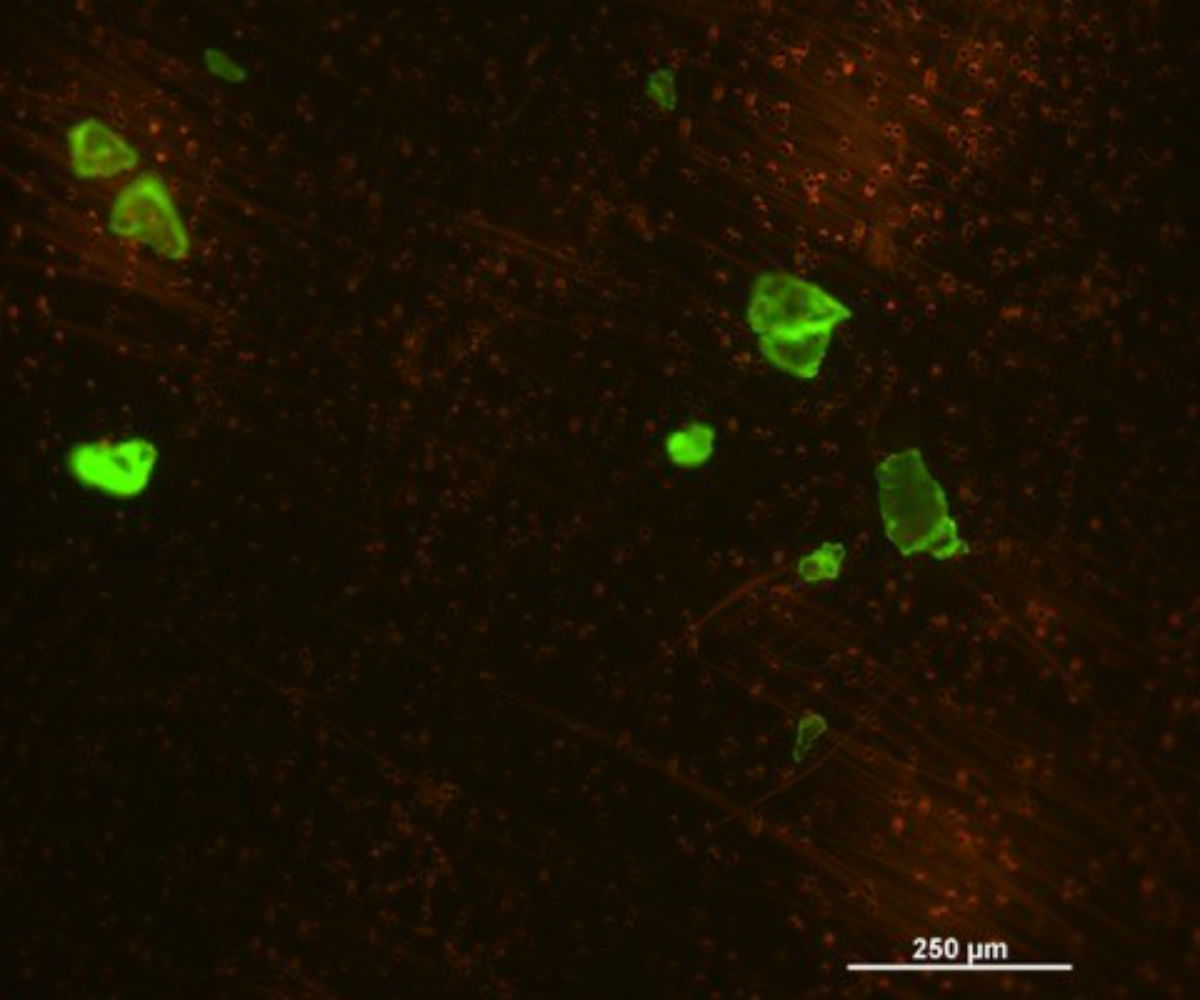

The dye specifically binds to plastic particles, and renders them easily visible under a fluorescence microscope. This allows scientists to distinguish microplastics amongst other natural materials and makes it easy to accurately quantify them. The researchers took samples from surface sea water and beach sand from the English coast around Plymouth – and, after extracting the microplastics from these environmental samples, they applied their method and were able to quantify the smaller fraction of microplastics effectively.

The researchers also discovered that the greatest abundance of microplastics of this small size was polypropylene, a common polymer which is used in packaging and food containers – demonstrating that our consumer habits are directly affecting the oceans. Large plastic objects are known to fragment over time due to weathering processes, breaking down into smaller and smaller particles termed ‘microplastics’.

Microplastics are the most prevalent type of marine debris in our oceans, and their impact or potential harm to aquatic life is not yet fully understood, researchers said. Previous reports suggest that the amount of plastic waste found in the oceans only amounts to one per cent of what was estimated, so new methods like this are desperately needed to find and identify the missing 99 per cent of ‘lost’ plastic waste in our oceans, they said.