Stay updated with the latest sports news across Cricket, Football, Chess, and more. Catch all the action with real-time live cricket score updates and in-depth coverage of ongoing matches.

Measuring the bend: A look at the facility that is helping BCCI weed out chuckers

110 bowlers have been called for chucking or suspect bowling actions in domestic cricket this season.

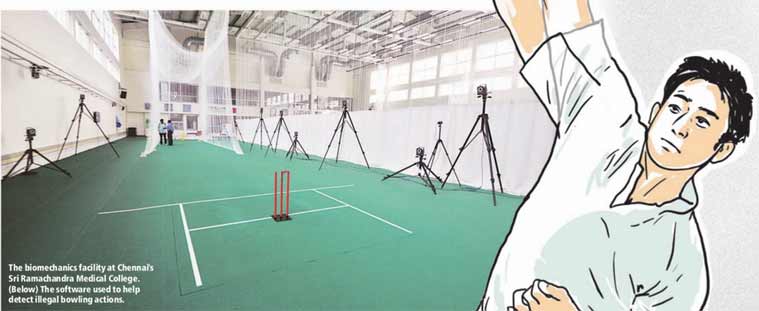

The precincts of a small biomechanics lab in Chennai’s Sri Ramachandra Medical College (SRMC) are reserved to check on suspect actions of errant bowlers and effect corrections. Sriram Veera visits the facility that is helping BCCI weed out chuckers

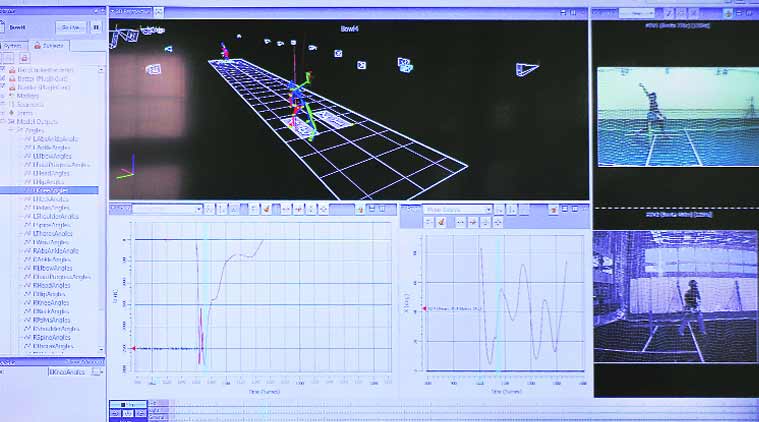

It’s a small glass-panelled room where two men in their 20’s are staring at their computers. Three dimensional images of stick figures shine in the screens, graphs populate the monitor corners, and inscrutable numbers scroll up by the side. The stick figures begin to flicker at the press of a button. “Look, look, we start from there. That arm which is horizontal to the ground. That’s the starting point,” says the excited voice of Gnanavel, one of the two biomechanists.

Last month, a solitary stick figure of Pragyan Ojha would have danced around that screen. A Vicon Nexus software would have stripped him of his human features, reducing him to a stream of data. This little biomechanics lab is where Ojha’s career hit a roadblock. This is where the Indian cricket board tries to prevent the chucking menace spreading through the nation. “This is the sanctum sanctorum,” says Dr Thayagarajan with a gentle smile. It’s the first such facility in Asia.

When Ojha would have entered the 150-acre property of Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute (SRMC) in Chennai, he probably would have glazed over the two million square feet of constructed space. His car would have snaked past a multi-specialty hospital, wafted past a ladies hostel, made way for girls and boys chatting away, books clasped to their chests, and glided around a football ground before taking a right to come to a stop at a shiny new building to face up with his worst fear. That he was chucking.

Ojha wouldn’t have entered the lab but he would have been visible to those two biomechanists Anees Sayed and Gnanavel through the large glass window from the lab. A large indoor multi-purpose training area saddles the large rectangular air-conditioned space where Ojha would have been strapped up topless with light-reflective markers on his body. 16 high-definition sensors would have zoomed into his body, capturing the light from those markers.

It’s basically indoor bowling nets. Ten cameras, mounted on tripods and six, on the side walls, stare down at Ojha. Two wall-mounted normal 2-D video cameras also look down on him. Around him, would have stood representatives from the BCCI — Diwakar Vasu, a former Ranji bowler who is a bowling coach these days, a board official, a biomechanist and if Ojha had been called in an international match, an ICC representative would also have been present. “If a bowler has a lot of variations – carom ball, arm ball, doosra and assorted stuff — he would have to bowl a lot more than three overs,” Thayagarajan says. All along the wall, wires run through a ledge, transporting Ojha’s data through to the lab.

Software used to help detect illegal bowling actions.

Software used to help detect illegal bowling actions.

He might have feared the worst already but Ojha wouldn’t have known his fate immediately. It could take a mindboggling 80 hours to say, Yes he chucks. And that’s assuming he bowled a set of three overs. Each delivery is rendered into 80 frames. Each frame has to be analysed separately. The points are marked in the arm, various angles and distances are spewed out by the software and the biomechanists get into micro assessment of each tiny little movement of the arm.

Analsye That

Sometimes, at the start of the second day, some 10 hours into analysing data, the moment of truth of chucking can hit. But for cases of significance, they wait for 80 hours to come up with the result. “Lives are involved here,” Thayagarajan says. “We can’t play around with sportsperson’s careers. We have to be absolutely sure.” The ICC gives them two weeks’ time to deliver the verdict of whether the bowler has an extension over 15 degrees or not.

It’s still a grey area and there is a lot of debate on the assessment techniques of the spin bowlers. The University of Western Australia is at loggerheads with the ICC these days. Their bone of contention is that since the spinners release the ball out of different parts of hand, which may or may not involve the fingers, automated marker tracking methods shouldn’t be used to identify the ball release. In March 2014, UWA, for long the only place of testing for bowlers, withdrew from its partnership with the ICC which rebutted UWA’s allegation by saying that it had provided its protocol to “a number of highly-credentialed bio mechanists associated with five different tertiary institutions across the world”.

Meanwhile, back in Chennai around the time that controversy had erupted, SRMC sports scientists were almost reaching an agreement with the Indian board and the ICC. The process had started seven years ago when the institution had started on its dream of producing world-class facilities for training, rehabilitation, injury prevention and correction to various sports in the country. They decided to use biomechanics to produce a customised solution for testing illegal bowling actions to get into the cricket space as well.

On the morning before Ojha arrived, a technician would have picked up a rod with a set of markers on it and walked into the nets area where the sensors are placed. He would have waved the rod, or the “wand” as it’s cutely called here, in front of each of those 16 cameras to calibrate the equipment.

It would have taken about half an hour for the calibration. The air-conditioning perhaps ran all morning that day but even when no one is there, the special Uni-turf floor requires a minimum of two hours of the AC. The wand too has to be waved every day irrespective of whether anyone is running in to save his career there, as calibrations have to be done on a daily basis. According to Dr Thayagarajan, the lab and the indoor nets area that houses the sensors, high-definition cameras cost SRMC about Rs 10 crore.

ICC approval

The wand was first waved several months ago when a young university graduate student from SRMC ran into bowl. The first of guinea pigs for the experiment. Unlike Ojha, and the other bowlers sent by the Indian board from various parts of the country these days, it was a day of happiness and excitement then. Dr Thayagarajan remembers it well. “Oh we were all excited. The boys had all sorts of dodgy actions. Some of them went over 40 degrees extension,” he laughs. After months of trials and once the confidence over the technology was gained, the BCCI got into extensive discussions with them sometime last year. The caravan had begun to move and the ICC specialists started to come in and after few more months of to-and-fro and ensuring that they could stick to the stringent testing protocol, ICC gave them the go-ahead.

“A player isn’t committing some grave crime when he is throwing,” MV Sridhar, director of cricket operations of BCCI, says. “Words like crime should not be used. One must never forget that.” We are trying to help them here to correct the mistakes. It’s a technical thing. We are here to help them find the problem and sort out the mistakes. Just not our contracted cricketers but various associations can send in any player to us and we can help them out.”

The centre is now ready to host players across Asia. For the Indians, especially, it’s a great facility to have right at home. No longer does one have to travel all the way to Australia or South Africa. They can just hop over to Chennai. It’s not going to save them if they possess an illegal bowling action, of course, but at least they can avoid the embarrassment of the test in an alien environment. And Indian cricket, which is now keenly interested in weeding out the chucking menace, has now a one-stop shop right at home where they can address the problem.

12 cameras, 80 hours …

# 10 cameras, mounted on tripods and six, on the side walls, stare down at the bowler being tested in a rectangular air-conditioned space. Two wall-mounted normal 2-D video cameras also look down on him as he bowls three overs.

# The bowler is strapped with light-reflective markers and the 16 high-definition sensors zoom in on him capturing the light from those markers.

# A bowling coach representative from the BCCI , a board official, a biomechanist and in case of international bowlers an ICC representative are present.

# If a bowler has a lot of variations – carom ball, arm ball, doosra and assorted stuff — he needs to bowl more than the three overs 3D image of the stick figure of the bowler shines on screens and a stream of data scroll up by the side.

# Each delivery is rendered into 80 frames to be analysed separately. The points are marked in the arm, various angles and distances are spewed out by the software and the biomechanists get into micro assessment of each tiny little movement of the arm.

# It can take up to 80 hours to affirm that someone is chucking.