A recent Supreme Court hearing on the long-pending delimitation in Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland has led to a new chorus of discord in tense Manipur.

Why is delimitation pending in Manipur, and what did the Supreme Court recently say in this regard?

In 2008, a delimitation exercise was carried out nationally based on the 2001 Census data. However, this was not done in Assam, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, as well as Jammu & Kashmir. Following years of political opposition to the exercise by the then state Congress government, primarily questioning the credibility of the 2001 Census data for Manipur, it became one of the four Northeastern states for which Presidential notifications were issued in 2008, deferring delimitation citing security issues.

This Presidential notification was rescinded in 2000, opening the door for the conduct of the exercise. In Jammu and Kashmir, delimitation was carried out in 2022, according to the 2011 Census, as specified in its Reorganisation Act of 2019.

In Assam, delimitation was completed in 2023, but based on the 2001 Census.

The Supreme Court has been hearing a petition seeking that delimitation be conducted at the earliest in the other three Northeast states as well. As things stand, Manipur last saw delimitation in 1976 which, in turn, was based on the 1971 Census.

Advocate Gaichangpou Gangmei, who is representing the petitioner, Delimitation Demand Committee for the State of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur and Nagaland, in the Supreme Court, told The Indian Express: “We have argued that the only way delimitation can be deferred is by a notification by the President under Section 10(A) of the Delimitation Act 2002, and that this had been rescinded in 2020. This means that the exercise has to be conducted and if for any reason, the Centre feels that it cannot be done now, it has to be deferred by another notification. The court also said this and has given the Centre three months’ time to explain its steps on this.”

Story continues below this ad

What has the response to this been in Manipur?

The fear that a delimitation exercise based on the 2001 Census was now imminent has caused demographic anxieties – already high in the state due to the recent ethnic tensions – to flare up in Manipur.

Currently, Manipur has 60 Assembly seats, of which 40 fall in the state’s central, Meitei-majority valley area, and 20 in the Naga- and Kuki-Zomi-majority hill districts. Except for the Kangpokpi seat, all the hill constituencies are reserved for Scheduled Tribes. Currently, the Assembly has 10 Naga MLAs and 10 from the Kuki-Zomi communities.

The 2001 Census had caused an uproar in the Meitei-majority valley areas because it showed high decadal population growth in the hill districts, particularly in nine subdivisions, where populations showed an increase by more than 40% between 1991 and 2001. In four of these subdivisions, the numbers had increased by more than 100% – 169% in Purul, 143% in Mao Maram, 123% in Paomata and 118% in Chakpikarong.

The apprehension then was that, in the absence of an increase in the number of constituencies (frozen till 2026 across the country, as of now), the valley could lose three Assembly seats to the hill areas.

Story continues below this ad

A delimitation based on the 2001 Census plays into these ethnic tensions, particularly when the two sides are already on the edge on account of the strife that began in May 2023.

Oinam Nabakishore Singh, former Manipur chief secretary and currently a JD(U) leader, points out that objections raised to the numbers thrown up by the 2001 Census had led to a revision.

“The abnormal growth numbers (in the hill areas) were impossible to explain on the basis of usual factors like birth and death rates or improved healthcare, and could only be possible because of massive immigration or false recordings. The state government asked the Registrar General and Census Commissioner to rectify these anomalies, and ultimately, the decadal growth rate for Purul, Mao Maram and Paomata was revised and reduced to 39% in each,” Singh says. But since no re-counting was done, he adds, “apprehensions persist”.

Valley-based parties across the spectrum are opposing delimitation based on these Census numbers. “We are in favour of delimitation happening in the state but not with the irregular and fluctuating 2001 Census data. It should happen now after the completion of the 2021 Census (which is delayed), so that it will be a regular and fair exercise,” says Manipur Congress chief Keisham Meghachandra Singh.

Story continues below this ad

But what is different about the new opposition to delimitation?

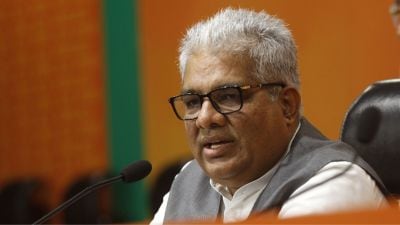

Amid the ongoing Meitei-Kuki strife in the state, a section of BJP leaders have put forward a new ‘precondition’ for delimitation: the creation of a National Register of Citizens. This was also underlined by Manipur Rajya Sabha MP Leishemba Sanajaoba in the Rajya Sabha last week, alleging “abnormal and illogical” increase in the number of Kuki-Zo villages in the state.

“In Kangpokpi, Tengnoupal, Chandel, Churachandpur and Pherzawl, since 1969 to 2024, the number of villages has increased from 731 to 1,624… That is 122% in about 50 years. In contrast, in the Naga-dominated areas, the increase is merely from 527 to 576 villages, a 9% increase. The figures speak of an eloquent volume of nefarious activities carried out by a particular community so as to capture political gains in Manipur,” Sanajaoba said.

“Illegal immigrants are trying to penetrate the administration. They are also playing electoral politics through illegal infiltration by taking advantage of the porous Indo-Myanmar international border. So my humble submission to the government of India is that before proceeding on any kind of alteration like a delimitation process… it is mandatory to detect the illegal immigrants first by implementing the NRC with the base year 1951, and deport them to their respective countries,” the MP said.

BJP MLA R K Imo, the son-in-law of former chief minister N Biren Singh, has separately written to the Union Home Minister stating this, besides raising another demand: to reserve the 40 Assembly seats currently in the valley for the “indigenous people of the valley”.

Story continues below this ad

What do leaders of Manipur’s other major communities say about this?

While BJP leaders’ statements are directed against the Kuki-Zomi community, party ally Naga People’s Front has made it clear that it does not oppose delimitation, “if and when it is officially initiated”.

“The NRC demand is an excuse to delay the long-pending delimitation since they don’t want to lose three MLAs (to the hill areas). The 2001 Census numbers were re-adjusted, so even that issue should not be there. Delimitation is a requirement, it has to be done,” says a Naga leader.

BJP Kuki-Zomi MLA Paolienlal Haokip also agrees, and has said the opposition to delimitation reflects resistance to sharing of power and resources. “The very fact that delimitation in Manipur is resisted by (the) majority community and any form of equitable sharing of power and resources is anathema to them strengthens the rationale for separate administration for hill/tribal communities,” he said on X.