The kaleidoscope of Indian politics has turned again. What does the regime change in Bihar, brought about by the “knight’s move” of Nitish Kumar, signify for the country as a whole? The knight on a chess board has a unique skill. Unlike the other pieces whose movements can only be linear, the knight can both shoot-and-scoot, move forward and backward, and crab-line, step sidewise. In the hands of a grandmaster, the knight can wreak havoc, simultaneously check-mating the opponent’s King while holding one of his major minions in the line of fire. The King, targeted, might escape by moving away if there is still some room to manoeuvre, but only by sacrificing the subordinate. The knight-errant from Bihar has done exactly that, and scored a local victory while still aiming at the jackpot in Delhi, two years on.

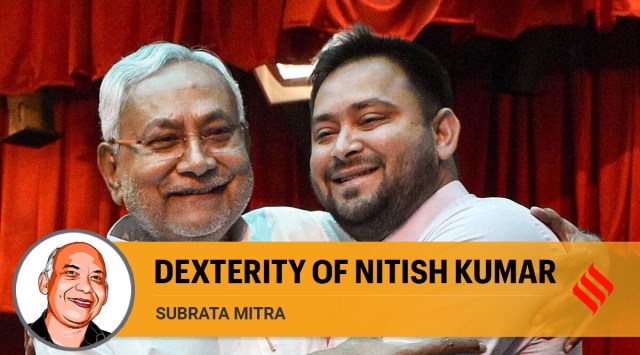

By all counts, it is a risky move. Despite the smooth regime change and re-allocation of portfolios without any visible squabbling, it is not clear if the resurgent RJD, the single largest party in Bihar assembly with a new elan in its gait, will continue to concede the same room to manoeuvre to Nitish as his previous partner. Under the leadership of young Tejashwi Yadav, the ambitious chairperson of the Mahagathbandhan, the RJD exudes the aura of a deeply entrenched regional party. It deftly combines the residual legacy of the JP movement with its M-Y network, still intact after the inter-regnum. In contrast, the BJP of Bihar, constrained by its extra-regional allegiance to Delhi and lacking a credible regional leader, cannot match it.

Be that as it may, the risky manoeuvre of Nitish Kumar has certainly breathed new life into the structure of Indian politics. Risk and personal accountability are the essential ingredients of dynamism in life. This is as true for the market as in politics. Risk-taking politicians and entrepreneurs churn the field, edge out the non-performing firms and non-functioning leaders, and generate new landscapes that are leaner and more efficient. Looking back to the 1960s, one can see how the risky manoeuvres of Charan Singh had unleashed the momentum that eventually led to the unravelling of the Congress system. It is not too far-fetched to anticipate a comparable polarisation, coming together of disparate constituencies, and the creation of the kind of anti-system coalition, that had brought down Indira Gandhi.

The prospect might appear calamitous to those who prefer stability at any cost to the painful and risky polarisation of political forces. However, structural implications for Indian politics loom larger over and above the gloom and doom, and euphoria, at the “betrayal” of Nitish. A dose of real competition, at the level of ideas and appropriate policies, is indispensable at the current juncture for the economy, and institutionalisation of the political process. In a democracy, office, or at least a real prospect of gaining office, are the only effective antidotes against the petulance of an ineffectual Opposition whose current politics consists mostly of sloganeering, obstructionism and working at cross-purposes. A realistic chance of gaining office might induce the fractious Opposition to move beyond the shibboleth of old slogans of “secularism” and social justice and spell out their collective visions in the areas of citizenship, completing territorial integration of the country, the role of the market in generating employment rather than additions to the state as the fountainhead of all bounties, and take a clear position on structural reform of agriculture.

The simultaneous presence of mass unemployment and inflation is a lethal mix for any party in power. The BJP cannot ignore the electoral threat of this huge potential of resentment, should it be deftly mobilised by a Nitish-Tejashwi-led Opposition. However, the likelihood of the new political constellation, causing the NDA coalition to lose some seats, as we learn from the latest opinion polls, need not necessarily be a catastrophe for the BJP. The temptation to become the new one-dominant party like the Congress in the old days, has added some slack to the sharp edges of its clear vision. A simple majority-based minimal-winning coalition, with the Opposition a whisker away from toppling it, can be therapeutic for the party. In structural terms, it might generate the kind of stable competition and political alternation between competing ideologies, championing different visions of the future, and strategies to enhance social cohesion, which is indispensable for a healthy and robust democracy.

In the long run, somebody has to bake the cake so that others can cut it up into equitable shares. How to combine this painful truth with the need to win hearts and minds, and votes, is the message that parties in the government and Opposition need to take on board as a matter of urgency.

The writer is Emeritus Professor of Political Science, Heidelberg University