In the days leading up to the Centre’s decision to stage a 10-hour parliamentary debate on Vande Mataram — a move perhaps heavily influenced by poll prospects in West Bengal — an ensemble of classical musicians performed the country’s national song on the day of its 150th commemoration.

PM Modi gave a speech right after, revisiting Jawaharlal Nehru’s decision to drop two stanzas from the original Vande Mataram by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, framing it as an act of appeasement toward Muslim leaders, which, according to the PM, “sowed the seeds of the division of the nation”.

But the status of a song also depends on the inherent idea that it is still a combination of melody, lyrics and rhythm, and is to be sung and performed. The musical structure of Vande Mataram, which is set in the evening raag Desh, comes with melodic lines that rest on emotional adornments.

One can hear these in Pandit Bhimsen Joshi’s voice as he sang it at the 50th anniversary of India’s Independence. The emotion was intact even when Pandit Omkarnath Thakur crooned it on All India Radio early on August 15, 1947 — India’s first day as an independent nation. Even though he chose his guru DV Paluskar’s composition in raag Kafi instead of Desh, and sang it with all the stanzas and not the truncated version, it is musically irresistible.

Both Thakur and Paluskar (also the founder of Gandharva Mahavidyalaya) attached mainly Hindu roots to Hindustani classical, not acknowledging the contribution of Muslim musicians and gharanas properly. There are stories of Thakur purifying the stage by sprinkling Gangajal on it to rid it of ‘unclean’ influences. A gifted musician, he expressed admiration for fascist leader Mussolini and his patronage of the arts when he met the Italian leader in Rome in 1930 and sang for him. He was also impressed by Mussolini’s wife making a vegetarian meal for him — a gesture he told music critic BVK Shastry about.

If one looks at the performance of the ensemble during the commemoration celebration of Vande Mataram last month, it was often off-key. But the failure was not theirs. It lay in the architecture of the melody. Its melodic backbone is not inherently built on rhythm. It is harder to navigate for an orchestra but it works splendidly in the solitude of a single voice. It moves like a lament, reminding us of the freedom struggle. Not like an anthemic march.

Desh is completely unlike the bright, morning raag Bilawal with all shuddh (natural) notes, in which Rabindranath Tagore composed Jana Gana Mana. Not only does the tune structure scream alignment with its staccato metre, it also has one phrase atop another, almost like a building which has various communities living in its different homes. Just like a nation. It is balanced, even if just for 52 seconds, allowing India to stand together in attention in the same key easily. That Bilawal is also equivalent to the Western major scale gives it a universality of sound across borders and regions. It is also perhaps why it was chosen over Vande Mataram.

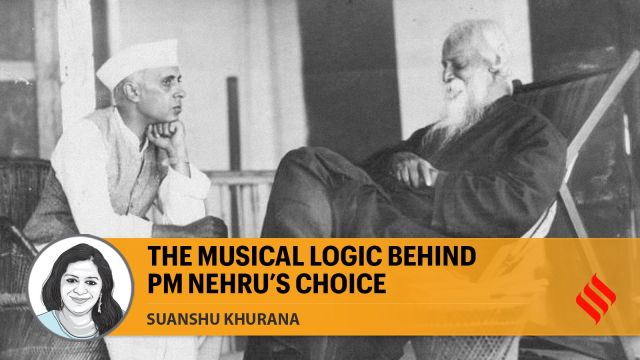

In his ‘Note to the Cabinet’, dated May 21, 1948, during discussions over national symbols, Nehru wrote, “Vande Mataram was associated with the struggle for our freedom. Hence it is bound to continue as a favourite national song which revives poignant memories,” adding that music-wise it was “plaintive, mournful and repetitive”.

“The music of the National Anthem is, therefore, the most important factor. A national anthem is to be full of life as well as dignity and it should be capable of being effectively played by orchestras, big and small, and by military bands and pipes. It is to be played not only in India but abroad and should be such as is generally appreciated in both these places. Jana Gana Mana appears to satisfy these tests,” he wrote.

Musically speaking, this is absolutely on point. Vande Mataram is sung to a mother; the latter to a republic. One promises intimacy, the other permanence. Both are and have been beloved in this country. The BJP would do well to grasp that Vande Mataram is secure, that removing the paras was an inclusive decision in 1937, while adding the paras now will be especially divisive. There are more urgent issues to be solved in India. The dignity of Vande Mataram, which is in place, is definitely not one of them.

The writer is Senior Assistant Editor, The Indian Express