Opinion The second chance

In Sri Lanka, a mandate to institutionalise checks and balances, strengthen the reconciliation process.

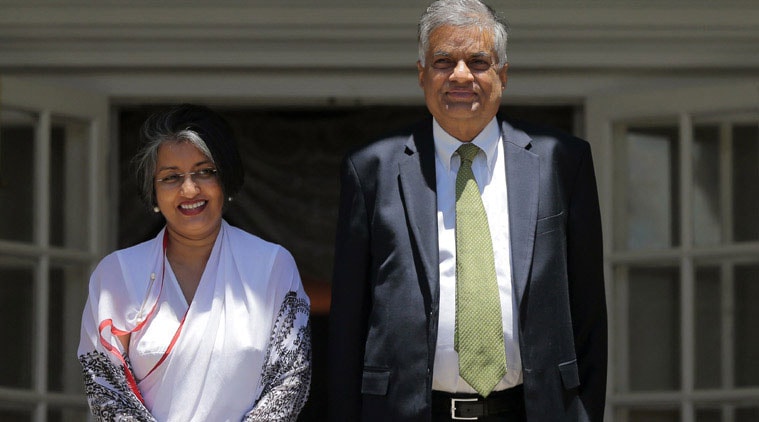

Sri Lanka’s prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his wife Maithree pose for photographs at their official residence in Colombo. (Source: AP photo)

Sri Lanka’s prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his wife Maithree pose for photographs at their official residence in Colombo. (Source: AP photo)

The Sri Lankan electorate has voted to sustain the changes that have taken place since the presidential election of January 8, when the common opposition candidate Maithripala Sirisena scored a surprise victory over Mahinda Rajapaksa. In the intervening seven months, a minority government headed by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe charted a shift away from the highly centralised and national security-dominant state structure that Rajapaksa had constructed to a more consensual mode of governance. In keeping with his election promise, Sirisena, with the backing of Wickremesinghe, championed the passage of the 19th Amendment to the constitution that reduced the power of the presidency, the scope for the abuse of power and strengthened parliament and state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police.

Rajapaksa sought to regain lost political ground by re-emerging as prime minister in the newly empowered parliament. Having grown accustomed to ruling like a king, without rules to stand in the way of his self-interest, and with the threat of prosecution for war crimes and corruption hanging over him, he thought that the way forward was to capture power in parliament. Instead, he faced the ignominy of a second successive defeat.

The same coalition of parties that helped Sirisena win the presidency, under the banner of the United National Front for Good Governance, fought the election promising good governance and the rule of law. The United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA), led by Rajapaksa, warned of the division of the country by Tamil separatists, international conspiracies to undermine Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and stalling of massive, and mostly, Chinese-funded development projects if they did not win the election.

This week’s election results closely parallel the presidential poll outcome. The UPFA won in the predominantly Sinhalese rural and suburban areas, where the lustre of the war victory over the LTTE remains high and people appreciate the earthy style of their former president. It lost heavily wherever there was an ethnically mixed population. Rajapaksa and his allies did not learn from the presidential election that they had to rebuild the trust of the ethnic minorities if they wanted their vote. Instead, they engaged in a strident Sinhalese nationalist campaign that portrayed the ethnic and religious minorities, and their international connections, as threats to the Sinhalese majority. This reinforced the sense of insecurity experienced by the minorities and turned their vote against him once again.

The memory of how the war against the LTTE ended, and what happened to the Tamil people in its immediate aftermath, continues to be a bitter memory among the Tamils. Although the end of the war also saw the end of the largescale human rights violations against them, they continue to feel that they are under threat. During the last period of Rajapaksa rule, there was also a rise in attacks against Muslims, their places of worship and businesses, which made all minorities, including Sinhalese Christians, insecure. These attacks, often led by nationalist Buddhist monks, were accompanied by police inaction. This smacked of the government’s complicity. The very poor performance of the Buddhist People’s Front, a Buddhist monk-led party, shows that the anti-Muslim sentiment of the past few years wasnot a bottom-up phenomenon.

The main significance of the verdict is that it paves the way for the transformation of two key areas of governance. The first is for the consolidation of the changes that followed the reduction in the arbitrary powers of the presidency. The process can be sustained since almost all the political parties that opposed Rajapaksa have agreed that the system of checks and balances needs to be strengthened. In addition, both Sirisena and Wickremesinghe have pledged to establish a government of national unity, drawing representatives from all the parties, which will ensure a de-concentration and sharing of power. The second important transition the country needs to undertake is to end militarisation and antipathy towards ethnic minorities and move towards a society that respects multi-ethnic and multi-religious features.

However, neither Sirisena nor Wickremesinghe has been specific about the plans for a resolution of the country’s protracted ethnic conflict and reconciliation. They, perhaps, did not want to present controversial proposals prior to the parliamentary election. But in the seven months after the presidential election, Sirisena and Wickremesinghe initiated the process of reversing the harsh policies of the past, reducing militarisation of the north and east, returning land that had been taken over for high security zones, permitting the national anthem to be sung in Tamil also, and repeatedly affirming that Sri Lanka is indeed a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country, as against one dominated by the Sinhalese majority. They also ensured that the police protected the ethnic minorities from attacks by nationalist groups.

Wickremesinghe is a man with a clear notion of what he wants and how to get it done. But he will be leading a potentially fractious coalition of parties, which includes Sinhalese hardliners, Tamil and Muslim parties, and those who have crossed over from the UPFA. In addition, Rajapaksa is unlikely to take his defeat lying down.

After he lost the presidential election, there was anticipation that he would retire.

But he came back to fight for the prime minister’s office. The new government will need to revive the economy that became debt-ridden, especially to China, balance its relations with China, India and the West, and cope with the international attention on human rights violations during the last phase of the war. It will also need to address longstanding grievances of the Tamils.

These are all difficult challenges and fraught with political consequence. If Wickremesinghe falters, the ever populist Rajapaksa will be waiting to return.

The writer is executive director, National Peace Council of Sri Lanka.