Opinion The Radical Teacher

For Randhir Singh, teaching was next to revolution-making.

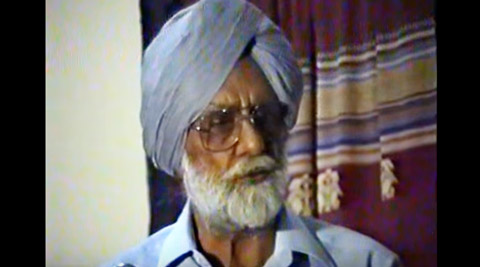

File photo of professor Randhir Singh. (Source: Screengrab/YouTube)

File photo of professor Randhir Singh. (Source: Screengrab/YouTube)

The news broke on social media late on January 31: Professor Randhir Singh, the great Delhi University professor of political theory, the passionate Marxist revolutionary, the man most loved by generations of his students and others whose lives he touched, was no more. I felt a certain numbness grip me and then, after a few minutes, a feeling of void took its place.

One knew he was 94, and ailing and weak. One knew, therefore, that the end would come some day. But when it came, it still sounded uncanny that it could happen to a towering figure like him. So much larger than life, he had become a living legend. How could his story come to an end?

Yet there was no denying that when the end came, the dream he had sought and worked to realise had, despite his lifelong efforts, slipped farther away than ever before.

I have been struggling to make sense of what he will mean to his country, people, students and colleagues in the days and years to come. What will he be from now on, beyond an ever-persistent nostalgia? What will be the lasting legacy of this once living legend? These are not easy questions to answer. But some clues can be found in his brief yet engaging autobiographical essay, “In Lieu of a Biodata”. He wrote it in 1988, just after he retired. But he already had half a century of activism behind him: As a student, as a communist, and finally as a teacher-activist.

The first part of the essay captures the passage from early years of idealism — fired by revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh and dedicated politics of the left — to the tempering of this idealism by the bitter-sweet experience of Independence and Partition, and the setbacks faced by the left. He narrates how he came to teaching: “Everything around me including my politics in shambles, I sought a new foothold in life. I started teaching”. But he also believed that “After ‘revolution-making’, teaching perhaps holds the maximum possibilities for a non-alienated life.”

The rest of the essay is about the vocation of a teacher-activist. Randhir Singh chose it fully aware of its potentialities as well as limitations: “What goes on… within the universities and social science institutes of the country, is only of marginal importance to the problems and prospects of Indian peoples’ struggle for better future… But this is where we work… And it is axiomatic that we make our efforts where we work, or we shall make no effort at all.”

He described his activism as “Robin-Hooding”, seeking to stretch the system to its limits. He privileged teaching over the pursuit of conventional academic scholarship. He wrote in a deceptive self-mocking style: “I have no research degrees and no publications … no string of scholars working ‘under’ me, no fellowships, no research projects, no study or other academic leaves, no ‘seminaring’, national or international, nothing, not even a visit abroad”. But he finds validation of his life as a teacher: “Students have come to my classes from other disciplines and other universities… and they have given me abundant love and affection, and thoughtful appreciation…” It is the students who first spoke of ‘a legend in Delhi University’.

What stands out the most from the essay is Randhir Singh’s convictions and tenacity. He chose not to be disillusioned by politics when mainstream politics, including left politics, took adverse turns. Instead, he chose to change the terrain of his politics: The battle of ideas and issues of ideological hegemony. And there, above all, he chose not to accept any of the “cooptive attractions the system has to offer even to a radical teacher”.

In a way, his life symbolised a famous passage from Marx, his chosen philosopher and guide: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

That, then, is his legacy, the takeaway from his life so resolutely lived. Many of us — of generations younger to him — find that the circumstances of mainstream politics have taken even worse turns in the recent past. And many of us — his students and colleagues — are part of what could continue to be a battle of ideas. How much we remain a part of this battle, the tenacity we show, will determine how meaningfully we remember the hero who has just passed away.