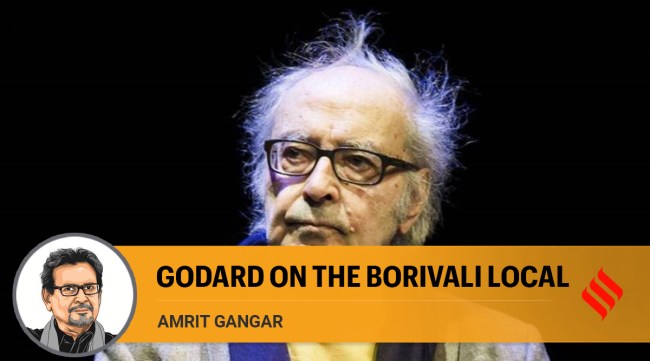

Opinion Jean-Luc Godard on the Mumbai local

Amrit Gangar writes: Cinema lovers all over India loved him and his works

Amrit Gangar writes: We thought Jean-Luc Godard would hit a century in the game of life, but he chose to bid a peaceful goodbye to us on September 13, 2022 at his Swiss home.

Amrit Gangar writes: We thought Jean-Luc Godard would hit a century in the game of life, but he chose to bid a peaceful goodbye to us on September 13, 2022 at his Swiss home. In 1982, Jean-Luc Godard was in the cans being carried on our shoulders, on a Bombay local train, as our film club Screen Unit had scheduled his debut film, A bout de souffle (Breathless, 1960), for a screening. The 16-mm prints had come from the National Film Archive of India, Pune. Those were not the days of CDs, DVDs or the ubiquitous “links”. Godard was an analogue man who could navigate his way through technological transformations. He adapted them the way he wanted and combated the hegemony of “capital”. All his practising life, he remained a model of inspiration for young cineastes across the world.

Eight years ago, I was at the gallery Espace Croisé in Roubaix in northern France, presenting an Indian film programme. Someone said that Godard was conducting a masterclass at a nearby art centre. I rushed there but he had left by then. I wanted to tell him about the strange chemistry that I had curated and created through my “Shakespeare and Cinema” sessions in Mumbai, including Grigori Kozintsev’s Russian Hamlet (1964), Akira Kurosawa’s Japanese Macbeth, Throne of Blood, (1957) and Godard’s French King Lear (1987). Godard would have laughed at this cocktail. The Dogme 95 version of King Lear (The King is Alive by Kristian Levring in 2000) wasn’t yet born then. Godard’s King Lear imbued the Shakespearean play with the experimental verve of the French New Wave.

The “virus” as he called the pandemic, had actually made Godard’s “virtual” presence global, as if he was intimately talking to us from his far-off Lake Geneva home in Switzerland, smiling and cracking jokes at 91 like a 19-year-old boy! He imbued our ideas with youth, igniting them. Only three years ago, in 2019, he was at Lausanne (Switzerland) receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). In the conversation, he was his usual witty and intellectually agile self. “Everything is archive,” he said, adding, “And in real life today, the present can be archived, and the past can be (archived), we could call it renewed, resuscitated. There’s almost the same relationship as the one between fiction and documentary.” What Iranian film critic Youssef Ishaghpour, in his conversation with Godard aptly calls the “urgency of the present, redemption of the past”.

Godard never came to India and apparently, he knew almost nothing of Indian cinema, but cineastes all over this country loved him and his cinematographic works, as well as his thoughts about life and language. His film Adieu au Langage (Goodbye to Language, 2014) experimented with 3D, narrating two simultaneous stories of nature and metaphor, focusing on two couples along with Godard’s dog Roxy. It is a melange of many references to literature and science, philosophy and political theory.

Godard’s eight-part video project titled Histoire(s) du cinema, which began in the late 1980s and was completed in 1998, is a 266-minute-long quintessentially complex work. It explores and examines the history of the concept of cinema and how it relates to the 20th century, resulting in typical Godardian critique. This film is considered to be Godard’s magnum opus. He enjoyed playing with language and words in French. Histoire(s) du cinema could, for instance, mean both “history” and “story”; the letter “s” in parentheses would suggest a sense of plurality. All through his filmmaking practice, Godard struggled to get back to the roots. In Le Gai Savoir ( Joy of Learning, 1969), for instance, a character says, “The problem is: To get back to zero.” The film that was banned by the French government adapts Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s treatise on education.

We thought Jean-Luc Godard would hit a century in the game of life, but he chose to bid a peaceful goodbye to us on September 13, 2022 at his Swiss home. During his lifetime, he thought, wrote and spoke extensively, he smiled at the “virus” and remained busy all his life. Godard’s last film Le Livre d’Image (The Image Book, 2018), examines the history of the modern Arab world. He broke the rules, innovating new ways of provoking cinematographic images and sounds — an oeuvre that will, in every way, make an epical textbook for students of cinema.

We had screened most of Godard’s popular iconic films, including Le Petit Soldat (The Little Soldier), Vivre Sa Vie (My Life to Live), Les Carabiniers (The Carabineers), Week-end (Weekend), Le Mepris (Contempt), etc. Of all his films, My Life to Live emotionally moved us the most as we saw the young Parisian woman in her twenties, Nana (Anna Karina) crying while watching The Passion of Joan of Arc in a cinema house in one of the film’s scenes. As an artist, Godard had this ability to move both your heart and mind.

Inside the cans on our shoulders on the 17:05 Borivali local, Breathless is getting restless and wants to “jump cut”. With his very first film, Godard created new ways of editing to narrate an elliptical story. Breathless renewed the cinematographic innovation which continued through his 63-year-long journey. Until the summer of 1959, G wrote regularly for Cahiers du Cinema. He suspended all critical activity to film Breathless between August and September 1959 — the year same year that marks the birth of the French Nouvelle Vague (New Wave).

We won’t say “adieu” to you, Monsieur.

The writer is a Mumbai-based film theorist, curator and historian