Opinion How to fix India’s urban water crisis, from Bengaluru to Chennai and beyond

Questions on water supply and quality should lead to a rethink of the centralised delivery system

There are caveats, though. Not everyone can afford water sold by private players. The WHO’s concerns about the reverse osmosis method used by the industry to purify water — it robs the water of essential minerals — are also valid.

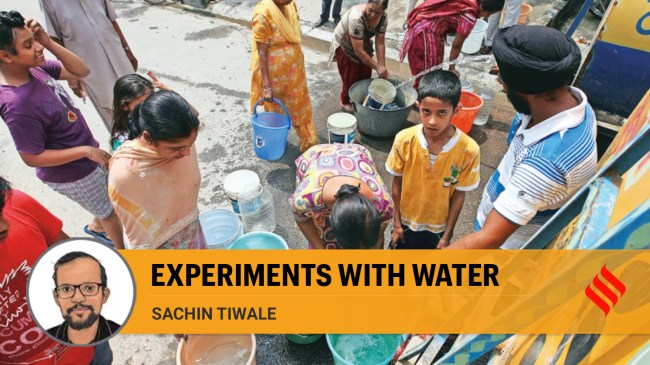

There are caveats, though. Not everyone can afford water sold by private players. The WHO’s concerns about the reverse osmosis method used by the industry to purify water — it robs the water of essential minerals — are also valid. Bengaluru is experiencing its worst water crisis in decades. The weak monsoon last year has compounded an already difficult situation caused by unregulated urban growth and depleting groundwater resources. Chennai too has experienced shortages in recent years. Several other Indian cities are under similar stress, indicating that water supply is rarely factored in urban planning.

It’s also worrying that a large section of India’s urban population does not receive safe drinking water. Last month, the Pey Jal Survekshan revealed that only 10 per cent of Indian cities meet drinking water standards.

The quality of water is known to deteriorate in the distribution network because of multiple factors — compounds from old pipes releasing into the water, sediment buildup and the accumulation of pathogens. This is a concern in several places, including developed countries. The problem gets compounded in Indian cities because of leaky pipes, many of which are close to sewer lines.

In the last two decades, this deficit has been exploited by companies manufacturing water purifiers and those selling packaged drinking water (PDW). Household dependence on drinking water sold in 20-litre jars has increased across the country. According to a recent study, 38 per cent of households in Kolkata and 70 per cent of households in Chennai routinely purchase water jars despite having access to piped water.

The PDW model that relies on decentralised treatment of water and non-pipe mode of delivery has evolved in the last decade-and-a-half — it involves a range of players including multinational companies and local operators who provide doorstep service. With an independent water source, mainly groundwater, and an established chain of manufacturers, distributors, and retailers, the model scores on the reliability criteria.

According to the standards of the Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation — the technical wing of the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs that sets norms for water supply and sanitation — Indian cities have a daily per capita water requirement of 135 litres per capita. Under the current piped water supply approach, all of this water is treated to meet drinking water quality standards. However, a person requires only a fraction of this amount for drinking and cooking purposes. The practice of treating enormous quantities of water to drinking water quality standards and distributing it through a network that cannot guarantee safe delivery needs examination. Considering the capital-intensive nature of the distribution network and constraints on repair and maintenance, we need to segregate water for drinking purposes and other domestic uses.

The model of decentralised treatment and non-pipe mode of drinking water delivery, followed by the PDW industry is promising. Bengaluru’s recent crisis has pushed the city’s authorities to experiment with water ATMs. Such initiatives are at an early stage in some other cities including Delhi.

There are caveats, though. Not everyone can afford water sold by private players. The WHO’s concerns about the reverse osmosis method used by the industry to purify water — it robs the water of essential minerals — are also valid. Acknowledging the feasibility of decentralised water treatment and supply does not rule out conversations on appropriate technologies. More experiments to evolve affordable and context-specific institutional arrangements, including those related to technology, need to be undertaken. Piped water supply too evolved over centuries because of a series of technological and institutional improvements. It is time to look for an alternative model of water supply to overcome the water quality issues. Decentralised treatment and non-pipe mode of service delivery are worth experimenting with.

The writer is a Fellow, Centre for Environment and Development, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bengaluru