Opinion Could Supreme Court have done justice in Chandigarh if EVMs were used?

The question that arises is: If the powerful can bend the law for a minor mayoral election, what might they do or not do when a five-year term for governing an entire state or the entire country is at stake?

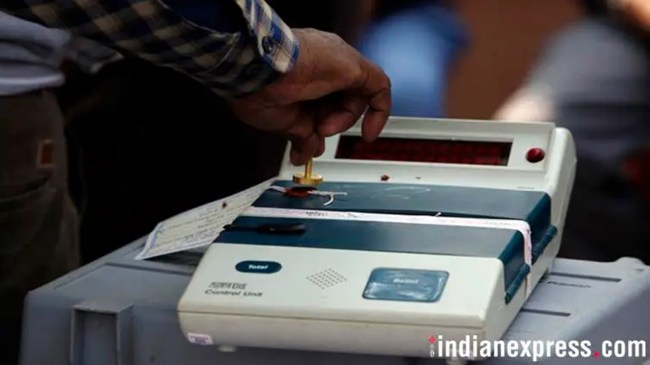

Given the vast expanse of the country and extremely varying levels of access to high-tech and comfort in using hi-tech products, it might be time to acknowledge the realities of India and move towards the once popular concept of appropriate technology. (File Photo)

Given the vast expanse of the country and extremely varying levels of access to high-tech and comfort in using hi-tech products, it might be time to acknowledge the realities of India and move towards the once popular concept of appropriate technology. (File Photo) Written by Jagdeep S Chhokar

The editorial, ‘Small poll, large lesson’ (February 24) that appeared in this newspaper, is absolutely to the point. “Small poll” is a justified label because there were only 35 votes to be polled and counted in the election for the mayor of the Chandigarh Municipal Corporation. The lesson is indeed “large” because the election can justifiably be considered a microcosm of the larger electoral system in the country. Let’s look at what happened.

The Chandigarh Municipal Corporation has 35 elected councillors. The BJP had 14 councillors, AAP had 13, Congress had 7, and one councillor belonged to the Akali Dal, a former ally of the BJP. The MP from Chandigarh is an ex-officio member of the corporation. Since the current MP, Kirron Kher, is from the BJP, the BJP has an extra vote.

The AAP and Congress had put up a joint candidate, Kuldeep Kumar. The BJP had put up Manoj Sonkar. After the voting, the examination of ballot papers and counting by the Presiding Authority were captured on CCTV. The Presiding Officer was seen signing the ballot papers and marking some ballot papers, and a din was heard. As soon as this process was over, the Presiding Officer got up and the BJP candidate, Manoj Sonkar, was made to sit on the chair and slogans praising his win were raised.

The official result, as declared, said 16 votes were cast for Manoj Sonkar, 12 for Kuldeep Kumar, and 8 were declared invalid.

According to the known and declared pre-voting affiliations, Manoj Kumar was expected to get 16 votes (14 BJP councillors, 1 MP, and one Akali Dal councillor) and Kuldeep Kumar was expected to get 20 votes (13 AAP councillors and 7 Congress councillors). By inference, it was clear that the 8 votes declared invalid were those of the AAP and Congress councillors.

A case was filed in the Punjab and Haryana High Court but finally reached the Supreme Court, and the editorial on February 24 was a comment on the Supreme Court judgment.

The mayoral election and its aftermath, including the SC’s judgment and the observations of the bench, raise a critical question.

The editorial says, “It took a relatively minor election of a municipal corporation mayor, for a term of one year, to lay down an important red line for those who would seek to bend due process to their will to win.” The question that arises is: If “those who would seek to bend due process to their will to win” can do this for “a relatively minor election of a municipal corporation mayor, for a term of one year”, what might they do or not do when a five-year term for governing an entire state or the entire country is at stake?

This is not a question that is thrown up frivolously. It is a serious question, particularly given the large-scale disaffection being expressed by a variety of groups about the existing voting system.

While the disaffection is usually expressed as being against EVMs, it is actually against the EVS, the current Electronic Voting System, a system consisting of two other machines in addition to the EVMs: the VVPAT machine (Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail machine), and a Control Unit or Counting Unit. It is the linkages between the three machines which comprise the EVS that obfuscate the transparency of the voting and counting. It is this lack of transparency which raises doubts in the minds of voters.

All solutions suggested by technical experts veer towards using even more complex technology. Given the vast expanse of the country and extremely varying levels of access to high-tech and comfort in using hi-tech products, it might be time to acknowledge the realities of India and move towards the once popular concept of appropriate technology.

A possible solution that has been suggested using the simplest technology possible for this purpose is as follows: Since the EVMs have been in use for quite some time and voters, in general, are familiar with their use, they should be retained. The VVPATs and Control Units should be removed, and replaced by a simple printer capable of printing a slip showing (a) the name and party symbol of the candidate that the voter voted for and (b) a bar code which enables machine counting of the slips.

The paper on which the above information is printed should be of good and durable quality capable of retaining the printed information for seven years (as opposed to the current paper from which the printed matter reportedly disappears after a rather short time).

The voter should be able to collect the slip from the printer directly (without any election official having to intervene or assist the voter in any way) and place the slip directly in a common ballot box. All the slips in the common ballot box should be machine-counted based on the bar code printed on each slip. This counting process using machines based on the bar code should not take many days as apprehended by the ECI whenever demand for a hundred per cent counting of VVPAT slips is made, and in which even the Supreme Court has had to intervene in the past.

The proposed solution is obviously open to discussion, debate, criticism, and modification but I believe it does deserve to be considered.

Before commentators and critics express their valued opinions on this proposal, they are requested to ponder over what might be called one of the final questions: What would have happened if the election for the mayor of the Chandigarh Municipal Corporation was held with EVMs, VVPATs, and Control Units? Without knowing about or commenting on the innards of the current EVS, the question arises: What would the Supreme Court have examined and how?

The time, not only to think about but answer these questions, is now.

The writer is a concerned citizen, and a founder-member of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR)