Not by quotas alone

To be truly inclusive, government must expand the higher education system

By any measure Ashok Thakur v the Union of India will be a landmark in India8217;s social history. The Supreme Court on Thursday upheld the Central Educational Institutions Reservation in Admission Act 2006, saying it did not violate the basic structure of the Constitution. Therefore, the consequences of the legislation, passed unanimously by Parliament, will now flow: 27 per cent of seats in Central institutions of higher education will be reserved for socially and educationally backward classes SEBCs. The court has, however, added a rider that this quota be made unavailable to the 8220;creamy layer8221; among SEBCs and that the government review the policy in five years. In one stroke now, the country will usher in a comprehensive measure of affirmative action to widen access to higher education. It will, most immediately, test the preparedness of the government to deliver on the provisions of the legislation, and also on its promise to increase the number of seats in these institutions.

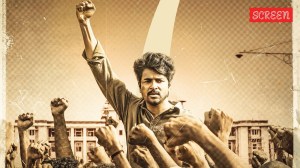

It takes a determined attempt to remember the street confrontations of the early 8217;90s to see how far this country has come in accepting the need for affirmative action. Then, the government8217;s announcement that it had accepted the Mandal recommendations had set off a churning in Indian politics. Today, a political and social consensus holds on the need to deepen equal-opportunity measures. This is not to deny that there is anxiety amongst large sections of the population that a door may be closing on their aspirations for quality higher education. There is. But that anxiety would have been present even if quotas for SEBCs had not been announced.

India is already running thin on meeting the aspirations of its young citizens for quality education. Take, for instance, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Each year, it takes just over 40 students for its MBBS programme. Whether half those seats are reserved or a quarter would not alter the fact that four dozen places annually for India8217;s best medical education is pathetically limited. So it is in different proportions at the IITs, the IIMs, our law schools and our universities.

These are shortages born of apathy, and they make salient the popular perception of a clash between equity and excellence, between meaningful equality of opportunity and merit. Those are false choices. Excellence is unattainable in a society with inequities. A programme of affirmative action would therefore be incomplete without expansion and improvement of our higher education system.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05