📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

Sarangi giant Pandit Ram Narayan, who gave the humble, demanding instrument a classical stature, passes away at 96

The last of a generation, and possibly the most famed sarangi maestro in Indian history, Pandit Ram Narayan, besides presenting khayal with much dexterity, will also be remembered for iconic accompaniment in films such as Mughal-e-Azam, Pakeezah and Kashmir ki Kali

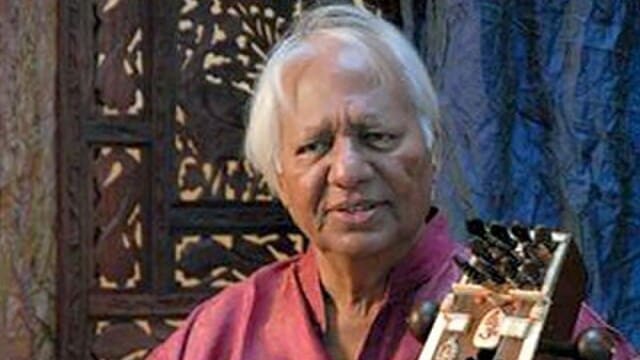

Sarangi player Pandit Ram Narayan passes away (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Sarangi player Pandit Ram Narayan passes away (Source: Wikimedia Commons)Chalte chalte – the pièce de résistance in Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (1972) – continues to beautifully describe Sahib Jaan’s knotty state of mind. Here was a courtesan, the educated poet and performer of the early 20th century and yet considered a fallen woman, who while performing for a nawab was also hinging herself on the idea that a tawaif, too, probably had the distant possibility of finding love. A spectacular piece of music; set along a looped tabla groove in Keherva, and Lata Mangeshkar’s fine voice, it comes with a haunting prelude – the pitch-perfect sarangi melody, romantic and traumatic in the same space, which defines the courtesan’s disposition. The prelude and the piece that followed remain etched in one’s memory.

Played by sarangi maestro Pandit Ram Narayan, who gave 21 takes for composer Ghulam Mohammad for the same before Mangeshkar sang Kaifi Azmi’s gentle poetry, Narayan’s sarangi riffs accompanied Sahib Jaan throughout the film. He plays the way the song is sung, imitating the sound of the voice on the instrument – a short-necked fiddle, played with a bow, infamous for being one of the hardest to tame and play. In K Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam, under the exacting baton of composer Naushad, Narayan shifted gears in Akbar’s court. While he accompanied Mangeshkar in the iconic Mohe panghat pe, as Akbar celebrated Janamashtmi, he brought in the confident flourishes packing a punch along the rebellious courtesan who professes her love for the prince in open court in Pyar kiya toh darna kya. And who can forget the accompanying sarangi riffs in SD Burman’s breathtaking Hum bekhudi mein (Kaala Pani).

Narayan, who single-handedly brought sarangi from the shadows of folk music and gave it the classical stature as a modern concert instrument, popularising it internationally by performing at the prestigious Royal Albert Hall and the BBC Prom concerts, passed away in Mumbai in the wee hours of Saturday due to age-related issues. He was 96 and is survived by four children including his daughter and sarangi player Aruna Narayan and sarod player Brij Narayan.

Born and raised in a small village named Amber near Udaipur, Narayan came from a family of court musicians, mostly vocalists in the Udaipur court. Narayan discovered sarangi at six and was initially taught by his father, who was concerned about two things – the difficulty that the instrument posed to be played and its association as the main accompanying instrument with the courtesans, which post the anti-nautch movement had degraded in status.

Originally a folk instrument, sarangi evolved as a significant accompanying instrument in Mughal courts and thrived, until it didn’t.

But looking at his son’s interest, Narayan’s father helped him learn from Uday Lal of Udaipur, a student of dhrupad singers Allabande and Zakiruddin Dagar. He then understood the tenets of khayal from Madhav Prasad followed by training under noted Lahore-based Kirana gharana vocalist Abdul Wahid Khan, who ran his gurukul with an iron hand..

Narayan joined All India Radio, Lahore in 1943 as a sarangi artiste. He moved to Delhi post the Partition and in 1948, accompanied renowned vocalist Amir Khan in his first AIR concert. As his knowledge of the artform grew, Narayan accompanied colossal names such as Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Pt Omkarnath Thakur and Hirabai Badodekar who showered him with much admiration. This was followed by three solo albums with HMV, almost never heard of for a sarangi player at the time and a successful career in film music. Besides Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeezah, his work also appeared in Taj Mahal, Milan and Kashmir ji Kali among others. Around the time Pt Ravi Shankar was taking sitar to an international audience first with tabla maestro Pt Chaturlal and then with Ustad Allah Rakha, Narayan also decided to do the same. Chaturlal, also Narayan’s older brother, accompanied him on his Europe tour in the 60s.

What followed was also a newer sarangi style – where he’d play a long alaap before accompaniment. He’d choose the bandish from the vocal style but perform the rest of the piece the way a sarod or a sitar player would. His finger technique and the glides resulting from it became the gold standard in playing the sarangi. As the Western audience appreciated him, the Indian audience followed. He remains one of the rare sarangi players, besides Ustad Sultan Khan in later years, who brought laurels to the humble sarangi to centre stage.

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05