Speak Easy: Games People Play

Games, by Irving Finkel, is a better souvenir than the Kohinoor.

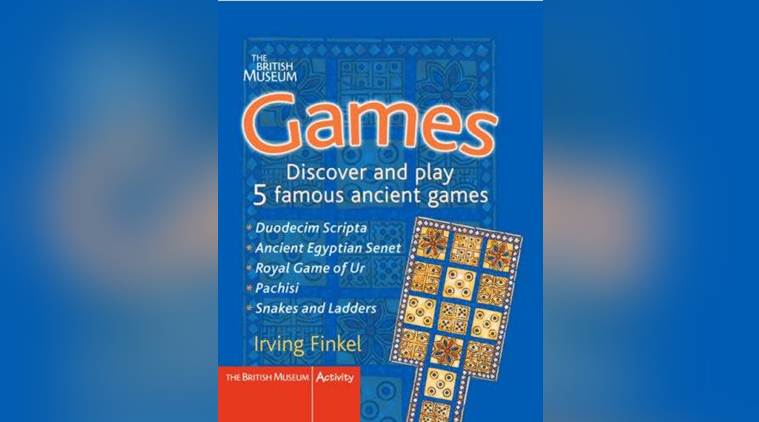

Irving Finkel’s Games (British Museum Press, 1995), contains five playable games from antiquity.

Irving Finkel’s Games (British Museum Press, 1995), contains five playable games from antiquity.

We, the formerly colonised, have weathered yet another Commonwealth Day, which used to be known, in less dishonest times, as Empire Day. A good time is generally had in London, where Meghan Markle made her first official appearance with the Queen, and had her body language analysed by the British press. For the former colonies, Commonwealth Day is an annual opportunity to wonder if we would have been happier had history and the English language left us alone. Also, to wonder how soon we’ll get our knick-knacks and baubles back from the British Museum and the Tower of London.

The Indians have been the least voluble in this department, of course, since we harbour a secret conviction that we wouldn’t have looked after those knick-knacks very well ourselves. It’s much more intelligent to have the English care for them on their taxpayers’ money, and bring back facsimiles from the museum gift shop. Not the Kohinoor, of course, but treasures like Irving Finkel’s Games (British Museum Press, 1995) a book which cleverly contains five playable games from antiquity, four of which have an India connection. Finkel, philologist and Assyriologist, is assistant keeper of ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and culture at the British Museum. More to the point, he is a keen student of board games and is celebrated for determining the rules of the Royal Game of Ur. Games is about a fifth as thick as the much more famous book concerning the holdings of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects, but is much more fun.

Finkel’s first game is Duodecim Scripta, shorthand for “Twelve Points”, which was as pervasive in the Roman Empire as Ludo is in India. It is a parent of backgammon which, Finkel writes, was “invented by sages in the court of ancient Persia around 600 AD… in response to a challenge from India.” A bit like in Finkel’s own work, they were challenged to deduce the rules of chess from the board and pieces alone. Their reconstruction was Nard, an early backgammon which is still played in the Middle East.

The Royal Game of Ur, which is dated to about 2,600 BC and was a favourite of the Bronze Age court before spreading all over the ancient Middle East, survived among the Cochin Jews, in a game named Aasha. Finkel suggests that its rules are derived from the original form of the Royal Game, in use during the first 2,000 years of play. In 177 BC, a Babylonian astronomer wrote out a set of rules for this Game of 20 Squares on a cuneiform tablet, complaining that things had become complicated with each piece being assigned a value, and people were reducing the Royal Game to gambling.

Senet, possibly the world’s oldest board game, about a millennium older than the Royal Game, was the Ludo of ancient Rgypt. Tutankhamun may have been a fan, since his tomb held double game sets for Senet and the Royal Game, both of which were racing games. One, pictured in the book, is built like a sled, which is rather apt for a racing game.

Those double boards are ancient and distant ancestors of the modern Indian tradition of boards combining Ludo and Snakes and Ladders. Apart from chess, which has a rather complicated history, these two games are India’s finest contributions to board gaming. Finkel reminds us that originally, snakes and ladders, known variously as Vaikunthapali or Gyanbaazi, provided moral training. The ladders represented virtues and the snakes vices and failings, and taught children the value of public morality. Sadly, the moral lessons were scrubbed off the board when the game to published in England, and when it was round-tripped back to India by the capitalist machine, it bore only numbers and all it could do was teach children to add.

Ludo was also round-tripped. It left India as the Pachisi at which Yudhishthir lost all but his life. It was sold as Parcheesi or Patchesi in the UK and the US, but in 1896, the long dice of Asia were dropped by English manufacturers in favour of the cubic dice of the Roman Empire, and Ludo was born. The name had to be Latin, naturally — ludo means “I play”.

The forces of international commerce brought Ludo back to India in about 1950, according to Finkel. Our country is now host to an unusual phenomenon — two forms of a game coexisting across a gulf of time. Pachisi, which dates back at least to Ajanta and Ellora, where it is first seen in frescoes, and which Akbar played with live pieces at Fatehpur Sikri, coexists with the modern, round-tripped Ludo. The shiny, modern game is avidly played under trees, in tea-shops and mechanics’ workshops, in homes and on mobile phones. And Pachisi remains a small-town favourite in a few states like Punjab and Rajasthan, wherever carpenters and tailors agree to make the pieces and the board. You need wood and cloth to play the original game, while the modern version thrives on paper, plastic and electronic screens, and neither seems to grudge the other’s popularity. One can’t think of any other game which has aged so gracefully.

Pratik Kanjilal lectures a surprisingly tolerant public on far too many issues.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05