How Pandit Birju Maharaj taught his students to be powerful like Jatayu and agile like a hen

Maharaj ji always rewarded the seekers, teaching them more than just dance -- he was a thought for a better world

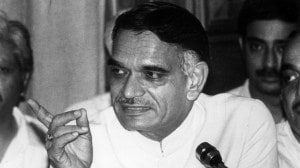

Pandit Birju Maharaj with his student, Navina Jafa. (Photo: Navina Jafa)

Pandit Birju Maharaj with his student, Navina Jafa. (Photo: Navina Jafa)Pandit Birju Maharaj stood with us, his students, on the lawn of the old Kathak Kendra building in central Delhi, in 1984. Looking at a tree, he said, “There is an entire world on the tree – the birds, their nests, the ants crawling in order; they coexist in a shared space. Look at the old leaves falling and the new red-veined ones… Like how we dance to a rhythmic time cycle, where one cycle finishes and a new one begins…”

Maharaj ji (as he was lovingly called) taught the seekers with generosity. He stands tall among classical dance gurus in creating Kathak as a constituency of an all-inclusive democratic world. Through Kathak Kendra, the National Institute of Kathak Dance, he nurtured and presented the form, making it a part of the eclectic and popular culture of the country.

His students and musicians are from different economic classes, gender, religions, regions and castes. “Once in the early 1980s, while living in the Kathak Kendra hostel, I was ill with malaria. My meagre scholarship did not cover the additional medicines and food expenses. Maharaj ji came to visit me and before leaving, he slipped a hundred rupee note,” recalls Shibli Mohammad, his student and now a famous guru and performer in Bangladesh.

Maharaj ji’s meditative knowledge of dance explored the universality of common images. “It was amazing to see him teach his Guyanese student, Phillip McClintock. It was the first production of ‘Katha Raghunath Ki’, an adaptation of Goswami Tulsidas’s Ramayana staged in 1977. Maharaj ji selected him to enact the role of Jatayu, the demi-god vulture. Phillip, who did not know the sacred text, was shown how to use his arms to enact the power of the wings. His arms, stomach, back muscles and his breath were in sync with the movement of his feet. Maharaj ji’s recreation of the persona of the vulture was one of rhythm and lucidity, communicating the clogged and frenetic power of the bird, with an innate spiritual character,” recalls Bipul Das, who came from Assam to learn with Maharaj ji in 1976. On stage, McClintock’s dark, naked torso was an engineered poetry of sinew and movement.

Maharaj ji’s philosophy of a well-balanced life combined sur (note), taal (beat), bhaav (emotion) and laya (rhythm). Mohammad remembers the time he arrived for his admission interview in Kathak Kendra, as a recipient of a scholarship from the Indian Council for Cultural Relations in 1982. He presented what he thought he had mastered, a unique composition called thaat, which is performed at the beginning of a performance, and is defined by sublimity and poise. Although he was selected, Maharaj ji chuckled and asked Mohammad, “Were you on a battlefield?”

Maharaj ji believed that the arts was an interconnected world of human creativity and transcended all mediums. Therefore, he encouraged us to observe dance in other art forms and not be limited to dance itself. “Observe when Pandit Bhimsen Joshi sings, the manner his body moves with the music, that too is dance,” he said.

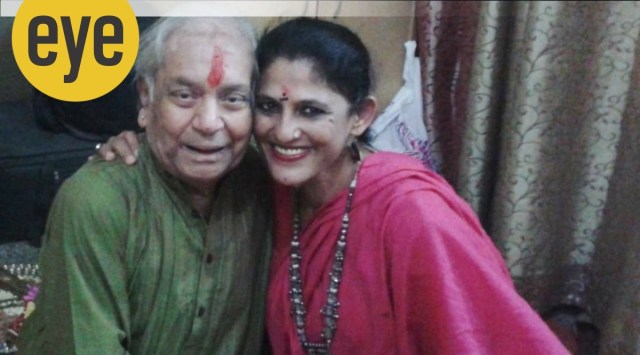

Maharaj ji was a self-taught percussionist, musician, poet, and painter. In 2017, as part of a programme organised by Centre for New Perspectives, a Delhi think-tank, I invited him along with his disciple Saswati Sen to direct 24 street folk performers representing 10 art forms to assist in repositioning them on stage and giving them a sustainable future. He deliberated with puppeteers, acrobats, magicians and snake-charmers with such humour and ease. He developed a production called ‘Dilli Ka Bioscope’, which was presented at the World Bank India office, the Delhi Gymkhana Club and the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. His training may not have created top performers, but it certainly ensured that many acquired a skill to earn a livelihood.

Maharaj ji with artistes during the production of Dilli Ka Bioscope in 2017. (Photo: Navina Jafa)

Maharaj ji with artistes during the production of Dilli Ka Bioscope in 2017. (Photo: Navina Jafa)

Maharaj ji used Kathak as a language to communicate universality, often leading to extraordinary creative pieces that centred around images of everyday objects and situations. He taught us complex footwork inspired by south Indian rhythmic patterns and syllables. Seeing us struggling to imbibe the composition, Maharaj ji explained using a mundane image: “Imagine three small chickens walking in a line behind the mother hen. Then one deviates and comes out of the line. The mother turns around, opens her wings and brings the naughty chick back into the line.” Within minutes we reproduced the exact pattern keeping the entire imagery in mind. Many students use this technique even today.

Shaky Singh, a student of Maharaj ji, with Sen and a few others took care of their mentor throughout the COVID-19 lockdown. Singh says, “Maharaj ji had adapted himself to online teaching, though he maintained that it could not replace the classroom. For this very reason, he taught not more than two students at a time. Many of them were old students in different parts of the world who knew his style and way of communication.”

His farewell was as grand as the legend himself. His students, led by Sen, recited the mantras of dance syllables; the flowers on his body reverberated his joyful spirit. In my last interview with him (for The Hindu, in April last year on his compilation of poems called Brij Shyam Kahe), I asked him, ‘Who are you?’. He replied, “I am without form and am merely a vichaar dhara (a thought process) to create a better world.”

Navina Jafa is a Delhi-based cultural heritage technocrat and Kathak dancer

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05