How caste-based genealogists have been preserving India’s history

These genealogists maintain ledgers that serve various purposes — court cases, property disputes and even intellectual property issues. However, better job opportunities mean this age-old tradition is on its last legs

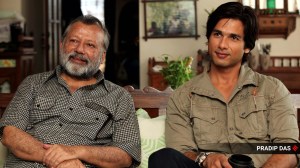

Genealogist Prabhu Lal from Kaithun village in Kotha district shows his pothi

Genealogist Prabhu Lal from Kaithun village in Kotha district shows his pothiWhen 65-year-old Yasin Maulani Chipa, an artisan from Pipad in Rajasthan’s Jodhpur district wanted to get a Geographical Indication (GI) tag for the area’s most famous offering, the Pipad block print, he sought help from an unusual quarter — his family genealogist. He travelled to Roopangarh in Ajmer district this January to learn more about his ancestral occupation.

“The genealogist told me that our family, which embraced Islam during the reign of emperor Firoz Shah Tughlaq, was in the block print business even then,” he said. “After we converted, the emperor commissioned us and a few other families to make clothes for soldiers with the Pipad block print.”

Armed with this information, he’s now doing the paperwork to seek the GI tag.

Considered India’s traditional record-keepers, genealogists maintain records of family lineages going back centuries. These ledgers serve various purposes — court cases, property disputes and even, as in Chipa’s case, intellectual property issues.

For instance, in March 2023, a district court in Ashok Nagar, Madhya Pradesh, used these family records to resolve a property dispute. In that case, the plaintiff claimed that his father had been adopted by his uncle, who had no heirs of his own, and that he was, therefore, the rightful claimant to the family property. The uncle’s brothers contested this, claiming no official record of this adoption.

The court ruled in favour of the plaintiff, and, in the absence of an official adoption certificate, it fell back on the family patiya or genealogy record.

Pandit Ashish with his ledger in Haridwar

Pandit Ashish with his ledger in Haridwar

A family and caste-based occupation

Traditionally, there are two types of genealogists: those who work in places where the Ganga flows and those who work in other places. Each caste group has different genealogists, who have a set of intergenerational patrons, called jajmans.

Typically, a genealogist would go to a jajman’s house and record information in front of the family and some witnesses in their pothis (record books), passed on from one to another. Everything goes on record — births, deaths, marriages, divisions in the family and even donations made for religious purposes.

According to Bansilal Bhatt from Kota district’s Kaithun village, genealogists see themselves as sons of the Hindu god Brahma. Bhatt, like his father before him, keeps records of Dhakad and Malav castes.

“I have records dating back 300 years in my house. We go to our jajman’s house, recite their history, and make new additions. In return, the jajman gives food, clothes, and money. Some jajmans have gifted cars and even land to their genealogists,” he said.

The script they use for this isn’t your typical Hindi — while some genealogists call it Brahmi, others claim it’s Betali. Since the occupation is patriarchal in nature, the script is only taught to men and passed on, like the ledgers, from father to son, even though women are sometimes known to take up the profession after the death of their husbands.

Ramprasad Srinivas Kuyenwale, a 73-year-old genealogist from Haridwar, has been practising genealogy since childhood, having learnt it at his father’s knee. According to him, genealogists — called ‘pandas’ in this Hindu holy city — have records of all those who go there to perform last rites.

“We preserve records dating back hundreds of years. In modern times, these records are very useful in courts. Many people who live outside India have started visiting us to get records of ancestral lands,” he said.

Because each genealogist caters to multiple generations in the same family, they cannot take sides in a family dispute. However, the pothis make for useful evidence, especially in property disputes.

The new Bhartiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023, also considers them valid evidence under Sections 26 (e) and (f), as both deal with proof to establish family relationships.

And it’s not limited to Hindu castes — as illustrated in Chipa’s case, Muslims too follow these genealogists. In a 2005 research project for which he was given a grant by the Union Department of Culture, Madan Meena, an artist and executive member of the Kota Heritage Society, found that there were even separate genealogists for women of royal families.

“There are people who keep records for Meenas, Rajputs, Baniyas, and Dalits. Some genealogists are assigned to royal family records. A Rajput genealogist cannot make a Jat his patron,” Bansilal Bhatt said, adding there were many Muslims who still follow this tradition.

On the flip side, being considered compelling evidence could mean that these records could end up in legal custody until the case drags on.

‘Pandit’ Ashish, another genealogist in Haridwar, cites how one of these ledgers had been tied up in a court that has now been going on for 20 years. “There’s information about other jajmans in that pothi too. That’s why most of us do not like to get involved in legal battles, especially in cases where we have to travel.”

Babulal Bhatt, national secretary of Rajasthan’s Vansh Lekhak Akademi — the state government’s official department concerned with lineages — believes genealogists played an important role in the 1857 rebellion, often considered India’s first freedom movement.

“Genealogists acted as messengers to make the public aware of British atrocities. For this, they used to go door-to-door. When the British realised the power of genealogists, they killed many and forced many others to migrate to different parts of India. This art of record keeping is a valuable tradition that needs to be protected,” he said.

Loss of interest, better job opportunities — why the genealogy is on its last legs

Dwindling interest in the traditional occupation combined with modern technology, better job opportunities and growing internet penetration has meant that only a handful continue to follow the profession. Even among those who still practise it, many have other jobs that give them a more sustained source of income and only do it as a side hustle to keep the tradition going.

The interest is still less among the young.

“There is a loss of interest among both jajmans and genealogists,” says Madan Meena of the Kota Heritage Society. “Patrons don’t feel the need to know their family history. As villages get more urbanised, the younger generation finds no interest in this tradition. Increasing migration to other parts of the country and even abroad means many have stopped it.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05