Explained: Up in arms against junta, the unquiet border states of Myanmar

On Tuesday, the Myanmar military bombed villages on its border with Thailand in retaliation for the loss of one of its outposts in the southeastern Karen (now renamed Kayin) state that the Karen National Union (KNU) had seized earlier in the day.

The air strikes sent hundreds of Karen, one of Myanmar’s many ethnic minority groups, scattering across the border.

The air strikes sent hundreds of Karen, one of Myanmar’s many ethnic minority groups, scattering across the border.Protests against the military coup in Myanmar have assumed new dimensions with some “ethnic armed organisations” (EAOs) mounting their own resistance against the junta, and the generals hitting back with airstrikes — a sign that they are ready to use the most brutal means to crush opposition.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

Tensions in several states

On Tuesday, the Myanmar military bombed villages on its border with Thailand in retaliation for the loss of one of its outposts in the southeastern Karen (now renamed Kayin) state that the Karen National Union (KNU) had seized earlier in the day.

The air strikes sent hundreds of Karen, one of Myanmar’s many ethnic minority groups, scattering across the border. According to reports in the online Irrawaddy news portal, early on Tuesday, KNU soldiers attacked and razed the military outpost near the Salween river, which runs along the country’s border with Thailand. The air strikes came hours later. Some 24,000 Karen people have been displaced in fighting since last month.

In the north, in Kachin state bordering China, and forming a trijunction with India, aerial bombardment has been going on for days since the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) attacked two police outposts and a military base at the Tarpein Bridge on April 11. There have been airstrikes there since April 15. Some 5,000 people are displaced.

Image made from video shows smoke rising from a Myanmar army camp near the border of Myanmar and Thailand on Tuesday. (Transborder News photo via AP)

Image made from video shows smoke rising from a Myanmar army camp near the border of Myanmar and Thailand on Tuesday. (Transborder News photo via AP)

In Myanmar’s western Chin state, which borders Mizoram, 15 soldiers were killed on Monday in two separate incidents, claimed by a new ethnic armed militia called the Chinland Defence Force (CDF).

Ten soldiers were killed after a convoy of trucks was attacked while it was on its way to reinforce the local base in view of increasing protests against the military. Another five soldiers were killed in a protest at another place in Chin state.

Federation dream unfulfilled

The resistance by the EAOs seems to have taken the Myanmar army by surprise. In all, 21 EAOs, and several more militias, are active in the border states of Myanmar. Many of them have been waging armed resistance against the state for decades now.

One of Aung San Suu Kyi’s priorities when her party was governing Myanmar from 2015 to 2020, was to take forward the efforts of her father, Gen Aung San, who led the movement for independence from the British, to build a federal Myanmar of the Bamar majority and ethnic minorities, who form one third of the country’s 54 million population.

But after a ceasefire agreement with 12 EAOs in 2015, the NLD government was unable to make much further progress — at least four more meetings held to bring the other groups on board were not successful. By the end of her first term, Suu Kyi was convinced that unless the army could be tamed through reforms to the country’s constitution, Myanmar would never became the federation that her father had envisioned.

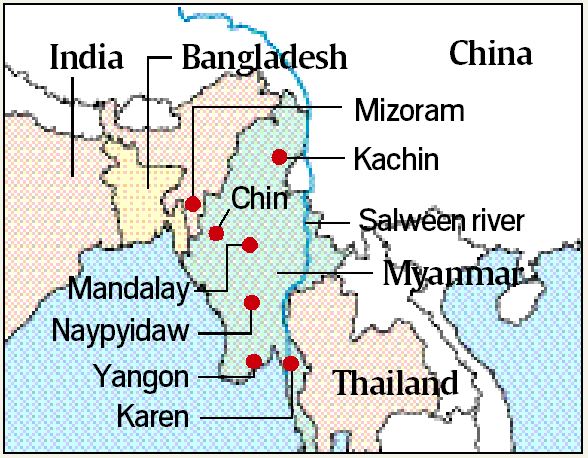

Fighting has broken out in Myanmar’s Kachin, Chin, and Karen states (map). (Transborder News photo via AP)

Fighting has broken out in Myanmar’s Kachin, Chin, and Karen states (map). (Transborder News photo via AP)

Bamars and the rest

The army draws its power from the divisions between the majority Bamar and the minority ethnic groups, and the hostilities between the ethnic groups themselves.

However, since the February 1 coup, some EAOs, including some that had signed the ceasefire agreement, have expressed solidarity with the pro-democracy protesters. The military had offered a ceasefire to all groups, but this was rejected by many of the influential groups, including the KIA and KNU.

The KNU was a signatory to the 2015 ceasefire, as was Chin nationalist Chin National Front (CNF). The latter group was among the earliest to rebel, with the families of hundreds of its members seeking refuge in Mizoram across the border.

Belying notions of divisions between the Bamars and the ethnic groups, reports from Myanmar say that in a throwback to protests of the 1980s and 1990s, many Bamar youth are now in Karen state for arms training.

The troubles in the three border states have distracted the army’s attention for the moment from the pro-democracy protests in the central regions, including in Yangon.

If more EAOs were to rise up against the army, joining hands or even fighting separate battles, Myanmar’s armed forces may find themselves engaged in multiple mini wars in the border regions at a time when it would like to focus on entrenching itself in the same way as it had done in the 1990s. According to a report in Nikkei Asia, the combined strength of the EAOs and other militias is about 1,00,000, while the Myanmar army is 350,000 strong. The use of air power by the military, according to the report, could be a warning to the EAOs to “back off”.

ASEAN’s plan for peace

It is perhaps due to the outbreak of fighting in these places that the junta has said it will “consider” a plan put forth by ASEAN for a resolution in Myanmar, but only “when stability is restored”.

The five-point ASEAN consensus plan was put to the head of the Myanmar army, Gen Min Aung Hlaing, in Jakarta over the weekend. The five points are: immediate cessation of violence by the Myanmar army; peaceful resolution through dialogue between all parties; mediation by an ASEAN special envoy; a visit by the special envoy; and humanitarian assistance from ASEAN.

The protesters have dismissed the plan, since it does not include the release of Suu Kyi and others arrested by the junta. The new generation of protesters have also demanded that the 2008 constitution, drafted and voted in by the military, should be scrapped.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05