The Hague-based International Court of Justice (ICJ) had ordered on July 17 that Pakistan must undertake an “effective review and reconsideration” of Jadhav’s conviction and sentencing, and grant consular access to him without delay. The ICJ upheld India’s stand that Pakistan is in egregious violation of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, 1963. READ MORE EXPLAINED NEWS

What is the concept of “consular access”?

Consular access simply means that a diplomat or an official will have a meeting with the prisoner who is in the custody of another country. Usually, during the meeting, the diplomat will first confirm the identity of the person, and will then ask some basic questions — on how he/she is being treated in custody, and what he/she wants.

Depending on the response, the diplomat/official will report back to his/her government, and the next steps will be initiated.

The principle of consular access was agreed to in the 1950s and 60s. The Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR) was framed in 1963, at the height of Cold War. This was a time when “spies” from the US and USSR were caught in each other’s countries and across the world, and the idea was to ensure that they were not denied consular access.

All countries agreed to the principle, and more than 170 have ratified the Vienna Convention, making it one of the most universally recognised treaties in the world.

Also Explained | How India intends to make its dams safer

Story continues below this ad

But, its implementation has faced challenges. While international law has long recognised the right of missions to assist and protect its nationals detained abroad, the ability of a consulate to provide effective aid has been heavily dependent on the prompt receipt of information of the detention, and timely access to the detainee.

Under Article 36 of the VCCR, at the request of a detained foreign national, the consulate of the sending State must be notified of the detention “without delay”. The consulate has the right “to visit a national of the sending State who is in prison, custody or detention, to converse and correspond with him and to arrange for his legal representation”.

No time interval is indicated for granting consular access. But it must be provided in all cases where a foreigner is “arrested or committed to prison or to custody pending trial or is detained in any other manner”, regardless of the circumstances or charges.

Indian diplomats in Islamabad were discussing the terms and conditions of the consular access to be provided to Jadhav.

Story continues below this ad

The key issues on the table: how many Indian officials would conduct Jadhav’s interview; for how long would they meet him; would Pakistani officials other than security personnel be present as well; would there be a glass partition between them and Jadhav; would they be allowed to have physical contact with him, etc.

After the ICJ order, the Pakistan Foreign Ministry had said Jadhav had been informed of his rights under Article 36, Paragraph 1(b) of the VCCR. It had said that Pakistan would grant consular access to him “according to Pakistani laws”, the modalities for which were being worked out.

India is arguing that Article 36, Paragraph 1(a) of the VCCR says “consular officers shall be free to communicate with nationals of the sending State and to have access to them. Nationals of the sending State shall have the same freedom with respect to communication with and access to consular officers of the sending State”.

India has asked Pakistan to grant “full consular access” to Jadhav in “full compliance and conformity” the ICJ verdict and the Vienna Convention. India wants to ensure that the meeting does not become a sham like the one in December 2017, when Jadhav’s mother and wife visited him.

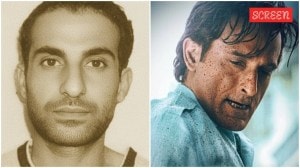

Jadhav, 49, a retired Navy officer, was arrested allegedly on March 3, 2016, and India was informed on March 25. He was sentenced to death on charges of espionage and terrorism in April 2017. (Illustration by Suvajit Dey)

Jadhav, 49, a retired Navy officer, was arrested allegedly on March 3, 2016, and India was informed on March 25. He was sentenced to death on charges of espionage and terrorism in April 2017. (Illustration by Suvajit Dey)