Nehru, Bose, or… Maulana Barkatullah? Who was India’s ‘first prime minister’?

In a recent interview, actress-turned-politician Kangana Ranaut claimed that Subhas Chandra Bose, not Jawaharlal Nehru, was India’s first prime minister. What did she mean?

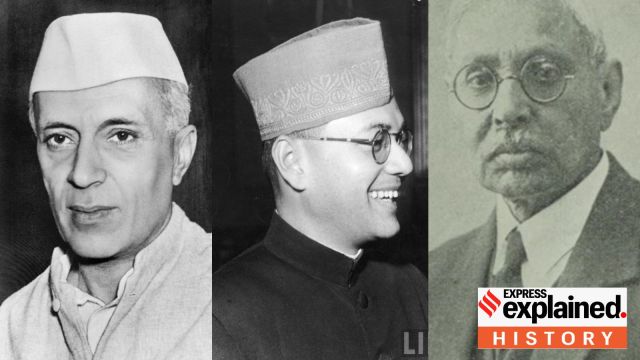

While both Subhas Chandra Bose (centre), and Maulana Barkatullah (right) did lead provisional governments, Jawaharlal Nehru was the first prime minister of Independent India. (Wikimedia Commons)

While both Subhas Chandra Bose (centre), and Maulana Barkatullah (right) did lead provisional governments, Jawaharlal Nehru was the first prime minister of Independent India. (Wikimedia Commons)Kangana Ranaut, in a recent interview, claimed that Subhas Chandra Bose, not Jawaharlal Nehru, was the first prime minister of independent India. After being criticised for the historicity (or lack thereof) of her comments, Kangana doubled down, citing the provisional government setup by Bose in 1943 as evidence of her claim. What exactly is she talking about?

All those who are giving me gyan on first PM of Bharata do read this screen shot here’s some general knowledge for the beginners, all those geniuses who are asking me to get some education must know that I have written, acted, directed a film called Emergency which primarily… pic.twitter.com/QN0jD3rMfu

— Kangana Ranaut (Modi Ka Parivar) (@KanganaTeam) April 5, 2024

The Azad Hind government

Subhas Chandra Bose proclaimed the formation of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind (“Free India”) in Singapore on October 21, 1943.

“In the name of God, in the name of bygone generations who have welded the Indian people into one nation, and in the name of the dead heroes who have bequeathed to us a tradition of heroism and self- sacrifice — we call upon the Indian people to rally round our banner and strike for India’s freedom,” Bose said in a fiery speech in the Cathay Theatre. (as quoted in Sugata Bose’s His Majesty’s Opponent, 2011).

Bose was the Head of State of this provisional government, and held the foreign affairs and war portfolios. A C Chatterjee was in charge of finance, S A Ayer became minister of publicity and propaganda, and Lakshmi Swaminathan was given the ministry of women’s affairs. A number of officers from Bose’s Azad Hind Fauj were also given cabinet posts.

The Azad Hind government claimed authority over all Indian civilian and military personnel in Britain’s Southeast Asian colonies (primarily Burma, Singapore, and Malaya) which had fallen into Japanese hands during World War II. It also claimed prospective authority over all Indian territory that would be taken by Japanese forces, and Bose’s Azad Hind Fauj, as they attacked British India’s northeastern frontier.

To give legitimacy to his government, much like Charles de Gaulle had declared sovereignty over some islands in the Atlantic for the Free French, Bose chose the Andamans. “It [the Azad Hind government] obtained de jure control over a piece of Indian territory when the Japanese handed over the Andaman and Nicobar islands in late December 1943, though de facto military control was not relinquished by the Japanese admiralty,” Sugata Bose wrote. The government also handed out citizenship to Indians living in Southeast Asia, and according to Sugata Bose, 30,000 expatriates pledged allegiance to it in Malaya alone.

Bose, looking at the Cellular Jail in Port Blair, Andaman. (Wikimedia Commons)

Bose, looking at the Cellular Jail in Port Blair, Andaman. (Wikimedia Commons)

Diplomatically, Bose’s government was recognised by the Axis powers and their satellites: Germany, Japan, and Italy, as well as Nazi and Japanese puppet states in Croatia, China, Thailand, Burma, Manchuria, and the Philippines. Immediately after its formation, the Azad Hind government declared war on Britain and the United States.

Not the first provisional government

Notably, 28 years before the Azad Hind government came into existence, the Provisional Government of India was formed in Kabul by a group known as the Indian Independence Committee (IIC).

Much like Bose allied with the Axis powers during World War II to fight the British, during World War I, Indian nationalists abroad (mostly in Germany and the US), as well as revolutionaries and Pan-Islamists from India, attempted to further the cause of Indian independence with aid from the Central Powers. The IIC, with the help of the Ottoman Caliph and the Germans, tried to foment insurrection in India, mainly among Muslim tribes in Kashmir and the British India’s northwestern frontier.

To further this cause, the IIC established a government-in-exile in Kabul under the presidency of Raja Mahendra Pratap, and prime ministership of Maulana Barkatullah, revolutionary freedom fighters who spent decades outside India trying to gather international support for Indian independence.

Barkatullah was also one of the founders of the Ghadar movement, which began in California in 1913, and aimed to overthrow British rule in India. Lala Har Dayal, one of the movement’s leaders put forth the following plan of action for the Ghadarites: “…use the freedom that is available in the US to fight the British…British rule must be overthrown, not by petitions but by armed revolt…carry this message to the masses and to the soldiers in the Indian Army…enlist their support.” (as quoted by Bipan Chandra and others in India’s Struggle for Independence, 1988).

While the movement was crushed in India by the end of the War, the Ghadarite left a strong and lasting impression on Indians and the British. “If success and failure are to be measured in terms of the deepening of nationalist consciousness, the evolution and testing of new strategies and methods of struggle, the creation of tradition of resistance, of secularism, of democracy, and of egalitarianism, then, the Ghadarites certainly contributed their share to the struggle for India’s freedom,” Chandra and others wrote.

The Kabul provisional government was one of many moves orchestrated by Ghadarite revolutionaries.

Acts of defiance & political necessity, not actual governments

Setting up provisional governments, and governments-in-exile, has long been a way for resistance movements to gain political legitimacy. Take, for example, the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) in Dharamshala. The very purpose of this government-in-exile is to challenge the legitimacy of the Chinese occupation of Tibet. By running a parallel government which claims to represent the will of the Tibetan people, the CTA keeps the flame of resistance burning, even when brutal repression and government-sponsored Han migration in Tibet has made things difficult.

Similarly, both the 1915 and 1943 provisional governments were, more than anything else, symbolic acts of defiance against British rule in India, made with certain political considerations kept in mind.

Bose proclaimed the Azad Hind government in order to legitimise his armed struggle against the British. By proclaiming a provisional government, he gave his army legitimacy in the eyes of international law — they were not just mutineers or revolutionaries, but soldiers of a duly constituted government. Crucially, citizenship oaths taken by Azad Hind Fauj officers were produced during the 1945-46 Red Fort trials as evidence of legality of their actions.

The Kabul provisional government was, on the other hand, proclaimed to establish the seriousness of IIC’s intentions, which it hoped would help gain the support of the Afghan Emir, who remained neutral but faced unrelenting pressure from the British to crack down on anti-colonial revolutionaries. In 1917, it even reached out to the Soviets, and as a government-in-exile right on India’s borders, posed a looming threat to the British.

That being said, neither of the two can, in any seriousness, be called the Government of India. This is for two main reasons. First, both these governments failed to gain widespread international recognition. While some countries did recognise and support them, they did so for their own motives. After the World Wars (in which the British emerged victorious), this support swiftly vanished. Second, both these governments never controlled Indian territory. While Bose did officially hold the Andamans, effectively, the islands were still under Japanese occupation. So was all the territory in the Northeast captured (briefly) by the combined Indian and Japanese armies. The Kabul government never set a foot on Indian soil, and in all seriousness, was a government only on paper until its dissolution in 1919.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05