The enduring political appeal of swadeshi — and why it is not necessarily good economics

Swadeshi has been one of the most influential ideas in Indian politics since the mid-19th century. But its empirical track record, as a guide for economic policy, has been wanting

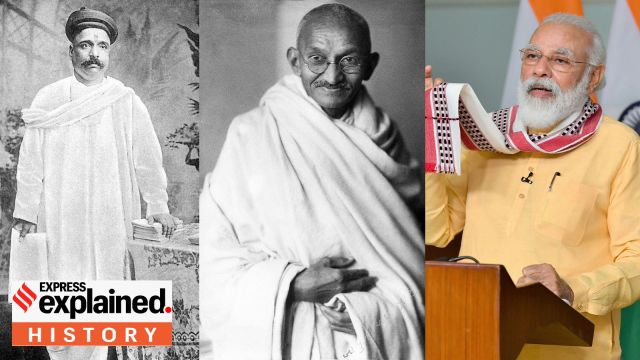

(from left to right) Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mahatma Gandhi, and Narendra Modi. (Wikimedia Commons, PMO)

(from left to right) Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mahatma Gandhi, and Narendra Modi. (Wikimedia Commons, PMO)As the government doubles down on its swadeshi push, Union Home Minister Amit Shah on Wednesday (October 8) became the latest member of the Union Cabinet to switch to the home-grown Zoho Mail.

This came days after the Ministry of Education issued a circular titled ‘Strengthening digital sovereignty under Swadeshi movement’ which directed officials to use the “indigenous” Zoho Office Suite for official work to “empower India to lead with homegrown innovation, strengthen digital sovereignty, and secure our data for a self-reliant future”.

The Sridhar Vembu-led Zoho Corporation is the latest corporate beneficiary of the government’s swadeshi mission. Previous experiences, however, provide a cautionary tale.

Most notably, in 2020-21, the government had embraced the Mohandas Pai-funded Koo, a microblogging platform, as an alternative to Twitter (now X). Despite its initial hype, fundamental flaws in Koo’s business model eventually caught up with the company which folded up last year.

In fact, even though swadeshi has been one of the most influential ideas in Indian politics for the last 150 years, its empirical track record, as a guide for economic policy, has been chequered. Here’s a brief history of swadeshi, and how it has influenced post-Independence economic policy, often to India’s detriment.

An economic idea…

The genesis of swadeshi as an idea can be traced to two interrelated criticisms of British rule: one, that colonialism was ruinous for India economically, and two, that it was pernicious to the nation’s culture and spiritual ethos.

The former criticism was articulated in various forms from the early- to mid-19th century onwards, including in rebel proclamations in 1857. But its most sophisticated conceptions were put forth in the late-19th, early 20th centuries by Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917) and Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848-1909) who argued that “on the whole, British rule was economically injurious to India and that perhaps it was designedly so”. (Bipan Chandra, The rise and growth of economic nationalism in India, 1966).

Dutt’s thesis on deindustrialisation — that the British destroyed traditional handicrafts of India, created a “helpless dependence” on agriculture, which in turn was ruined by excessive taxes — was in vogue, especially in Left intellectual circles, well into the 1970s-80s. Naoroji’s “drain of wealth” theory, on the other hand, showed how the Indian taxpayer was effectively paying the British for his own servitude.

This analysis of the Indian economy under British rule would provide heft to the argument for swadeshi. “India had been reduced to the status of supplier of raw materials and market for British manufactured goods,” the historian Sumit Sarkar wrote in Swadeshi Movement in Bengal, 1903-08 (1973), “[and] protection of what remained of the traditional crafts and a vigorous drive for industrialisation on modern lines were the obvious ways of ending this condition of dependence”.

…With moral dimensions

In a series of speeches in Poona (now Pune) in 1872, Mahadev Govind Ranade (1842-1901) spoke about “preferring the goods produced in one’s own country even though they may prove to be dearer or less satisfactory than finer foreign products”. (Chandra 1966).

The idea that the moral, patriotic obligation toward swadeshi overrode economic logic has been a central feature of the idea’s enduring political resonance — and its failures — over the years.

The greatest champion of swadeshi as a moral force was Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), who, in a 1916 speech, described it as “that spirit in us which restricts us to the use and service of our immediate surroundings to the exclusion of the more remote”. (Speeches & Writings of M.K. Gandhi, 1922).

This moral force operated across domains, from politics to religion to economics. Swadeshi, for Gandhi, was “the ‘law of laws’ ingrained in the basic nature of human being”, academic Siby K Joseph wrote in ‘Understanding Gandhi’s vision of Swadeshi’ in 2012.

In economics, for instance, swadeshi would mean that one “should use only things that are produced by my immediate neighbours” (Joseph 2012). Gandhi’s argument was borne out of moral considerations: “Economics that hurt the moral well-being of an individual or a nation are immoral and therefore sinful… It is sinful to eat American wheat and let my neighbour the grain-dealer starve…,” he wrote in Young India in 1921.

Deployment in politics…

During the freedom struggle, the political deployment of swadeshi occurred in the form of boycotts of British-manufactured goods, and the concurrent push for indigenous manufacturing and enterprise.

In 1896, Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) organised public burnings of foreign cloth in the Bombay Presidency, as a response to newly-introduced excise duties on manufactured Indian cloth. Less than a decade later, the first “mass movement” of the freedom struggle, the so-called Swadeshi Movement which was triggered by Lord Curzon’s decision to Partition Bengal, borrowed heavily from Tilak’s methods.

“That the message of boycott (of foreign cloth) went home is evident from the fact that the value of British cloth sold in some of the mofussil districts fell by five to fifteen times between September 1904 and September 1905,” Chandra, Mridula Mukherjee, Aditya Mukherjee, K N Pannikar and Sucheta Mahajan wrote in India’s Struggle for Independence, 1857-1947 (1989).

“Apart from boycott of foreign goods, boycott of government schools and colleges, courts, titles and government services and even the organisation of strikes” were carried out with the aim of making administration “impossible”. (Chandra et al, 1989).

During the Gandhian era of mass politics, the nationalist critique of colonialism that was disseminated among common people rested on “the twin themes of the drain of wealth and the use of India as a market for Britain’s manufactured goods and the consequent destruction of the Indian handicraft industries…”. (Ibid).

In many ways, swadeshi was the lingua franca of the freedom movement, which united people from various walks of life, and diverse cultures and backgrounds to fight for a common goal.

…And in policy

Beyond the rejection of foreign goods, swadeshi entailed embracing domestic industry. There was general consensus among Indian nationalists, including those on the Left, that industrialisation was necessary to uplift the country’s downtrodden masses. (Gandhi was the notable exception in this regard).

“The Indian national movement accepted from the beginning, and with near unanimity, the objective of a complete economic transformation of the country on the basis of modern industrial and agricultural development,” Chandra and others wrote. This modern industry would be owned by Indians, and operated for the welfare of the people.

By the 1930s, as the economic historian Aashish Velkar wrote, the concept of swadeshi had become a fulcrum for making capitalist demands.

“The notion that Indian capital needed to be used for the benefit of Indian nationals became established as a key principle within nationalist thought by the 1930s. This principle also formed a central tenet of post-independence development planning and protectionist policies,” Velkar wrote in ‘Swadeshi Capitalism In Colonial Bombay’ (2020).

Pitfalls of swadeshi

Nitin Pai, director of The Takshashila Institution, wrote in his 2021 paper ‘A Brief Economic History of Swadeshi’ that while the “fear of economic imperialism” drove Jawaharlal Nehru’s India to adopt a mixed economy model with a large role for the public sector, the use of “import substitution as a policy tool…eventually became an end in itself”.

The result: decades of protectionism with the stated goal of helping domestic industry find its feet. Economists have long argued that this protectionism, while allaying the insecurities of indigenous capitalists by shielding them from competition, was ultimately detrimental for the economy on the whole.

For one, protectionism made Indian companies uncompetitive, and as a result, decreased the quality of the product/service that the customer bought while increasing its costs. “…Sheltering domestic firms from international competition only imposes higher costs on consumers, reduces savings and investible surplus, and coddles the holders of licenses to diversify into other protected industries,” Pai wrote.

While there was ample evidence to make these arguments even in the Nehruvian years, it was the moral and political power of swadeshi that made it difficult to depart from this parth.

“The export pessimism which became fashionable in the late 1950’s and 1960’s had a fragile support in actual data and much more in dogma,” Lord Meghnad Desai said in a lecture in 1999. (‘What should be India’s economic priorities in a globalising world’).

It was only in the 1980s, as the Indian economy stagnated and amid a crippling balance of payments crisis, that the allure of swadeshi in the halls of power in New Delhi began to wane.

A recession & a reprise

As India opened up it economy after the landmark economic reforms of 1991, swadeshi took a backseat for a couple of decades. This was the high noon of globalisation around the world, the “end of history” as Francis Fukuyama had famously declared.

“The roughly two-decade-long era of…hyper-globalization…was characterized by the unprecedented fact of growth of world trade volume consistently outpacing increases in world GDP,” sociologist Tibor Rutar wrote in ‘The Rise and Apparent Decline of Globalization’ published in The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Geopolitics (2024).

But this hyperglobalisation, which upended old supply chains and industries, particularly in the West, while providing a ballast for countries in the Global South — China, India, Vietnam, among others — to grow rapidly, ended with the financial crisis of 2008. Since then, economic stagnation in developed countries, and growing popular resentment against offshoring and immigration, has created a new political and economic landscape for swadeshi.

After Congress pivoted towards a liberal-globalised outlook, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh had taken up the mantle of swadeshi in the 1990s. Born out of a fiercely nationalist view of economics, Sangh’s swadeshi pitch has found its legs over the last decade of BJP rule.

Although the BJP has frequently also championed easing FDI norms, since the beginning of Narendra Modi’s second term, the government has renewed its swadeshi push, in terms of both rhetoric and substance. The Make in India initiative and the emphasis on creating an Aatmanirbhar Bharat (Self-reliant India) echo the concerns and prescriptions that advocates of swadeshi have had since the 19th century — but in context of the supply chain disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and India’s difficult relationship with China.

But as past experiences show, an uncritical, dogmatic embracing of swadeshi may in the end be counterproductive. As Pai wrote, “the compass of economic nationalism is better pointed to samarthya (capability) rather than swadeshi. Capability does not mean everything must be produced within the borders of one’s own country, even if it can be. Rather, it suggests the power to access whatever is desired regardless of where it is produced.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05