Yellowstone celebrates 151st anniversary: The complicated history of the world’s first national park

While Yellowstone has been the location of many successful conservation projects, it is not the "pristine" wilderness that it is often considered to be, having been home to Native Americans for at least 11,000 years.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone by Thomas Moran was one of the many paintings, sketches and photographs from the Hayden expedition to be displayed in the US Congress. Images such as these were crucial in establishing the "pristine wilderness" myth. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone by Thomas Moran was one of the many paintings, sketches and photographs from the Hayden expedition to be displayed in the US Congress. Images such as these were crucial in establishing the "pristine wilderness" myth. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Yellowstone National Park, which celebrated its 151st anniversary earlier this week, is widely considered to be the first national park in the world. Its visitors’ brochure says, “The first US national park was born, and with it, a worldwide movement to protect places for their intrinsic and recreational value.”

Located in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho, it was established by the 42nd United States Congress with the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872. It spans an area of over 9,000 sq. km comprising lakes, canyons, rivers, iconic geothermal features such as the Old Faithful geyser, and mountain ranges.

Over the years, it has been at the centre of many successful conservation endeavours, and today is the most famous megafauna location in the contiguous United States, home to grizzly bears, wolves, and free-ranging herds of the endangered bison and elk.

However, there is also an often ignored history of the national park. “The big myth about Yellowstone is that it’s a pristine wilderness untouched by humanity,” anthropologist and author of Before Yellowstone: Native American Archaeology in the National Park, Doug MacDonald, told Smithsonian Magazine.

“Native Americans were hunting and gathering here for at least 11,000 years. They were pushed out by the government after the park was established,” MacDonald said.

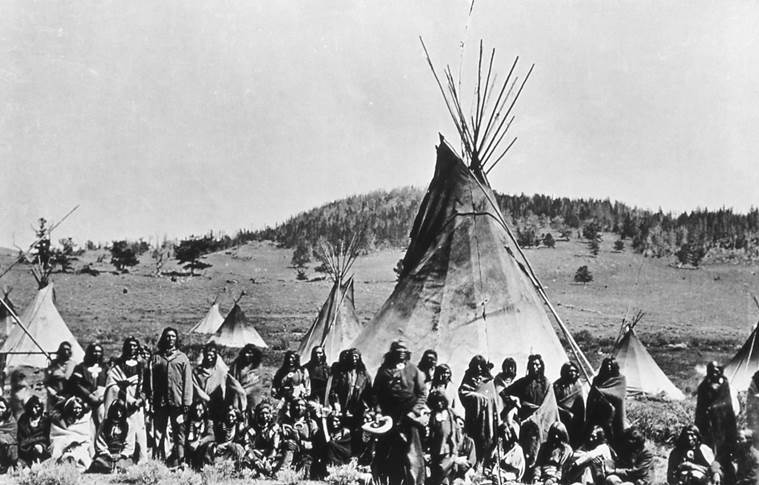

Washakie & his warriors (1871); Photographer: Unknown. Native Americans have been living in the lands now belonging to Yellowstone National Park for at least 11,000 years, as per oral histories and archaeological evidence. (Source: Yellowstone National Park’s Photo Collection, National Park Service, US Department of Interior)

Washakie & his warriors (1871); Photographer: Unknown. Native Americans have been living in the lands now belonging to Yellowstone National Park for at least 11,000 years, as per oral histories and archaeological evidence. (Source: Yellowstone National Park’s Photo Collection, National Park Service, US Department of Interior)

Establishing a ‘National Park’

The original legislation stated that Yellowstone would be “reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States,” and that it would be set aside as a “public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

In the lead up to Yellowstone becoming a national park, three major expeditions – in 1869,1870 and 1871 – raised public awareness of the area’s natural beauty. The last of these, known as the Hayden expedition, was particularly important.

Alongside the usual retinue of scientists, Ferdinand V. Hayden, the head of the US Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, brought photographer William Henry Jackson, and artists Henry W. Elliot and Thomas Moran along for the journey. It was the work of these men that captured the imagination of the United States’ public and lawmakers alike.

Actual motivations

While there were those like Hayden who were concerned about the desecration of Yellowstone due to those trying to “make merchandise of these beautiful specimens”, for US lawmakers, the actual motivation was different. Historian Richard West Sellers argues in Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History that “Congress was more interested in extracting resources and promoting tourism to the West than in promoting conservation.”

For instance, owner of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company, Jay Cooke, hoped to extend his railway lines from Dakota Territory into Montana Territory, including the area that now encompasses Yellowstone. Closing off Yellowstone to settlement and making it a tourist destination would be extremely profitable for his rail company, which would become the sole available mode of transportation to and from Yellowstone which lay in the still relatively less developed American West. Cooke was one of the biggest proponents of the national park proposal.

A bison at Yellowstone National Park in January 2023. The American bison was almost driven to extinction by settlers from the east. One of the main reasons why these animals were hunted in great numbers was to control the Native American population which depended on hunting these massive mammals to sustain themselves. An US Army saying from the time went, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A bison at Yellowstone National Park in January 2023. The American bison was almost driven to extinction by settlers from the east. One of the main reasons why these animals were hunted in great numbers was to control the Native American population which depended on hunting these massive mammals to sustain themselves. An US Army saying from the time went, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Ignoring the Native Americans

Whatever the reason might have been, since 1972, Yellowstone has been maintained as a pristine wilderness, with no permanent settlements. However, what this ignores is that the area had been home to many Native American tribes prior to being closed off for settlement.

“The park is a slap in the face to Native people… There is almost no mention of the dispossession and violence that happened. We have essentially been erased from the park,” Shane Doyle, a researcher and member of the Apsaalooke (Crow) Nation, told Smithsonian Magazine.

From archaeological research and oral history, it can be gleaned that at least 27 current Native American Tribes have connections to Yellowstone. However, when the national park status was being debated in Congress, there was next to no mention of the Native American presence. Once Yellowstone National Park came into existence, several different tribal groups who used to camp there were removed by the US Army.

“Creating a massive park in tribal lands was a distinct political act and it happened under a president who was fervently against Native peoples,” Matthew Sanger, a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, said in an interview.

The Old Faithful Geyser is one of Yellowstone National Park’s biggest attractions and is one of many of the park’s geothermal features. A popular American myth claimed that “Native Americans never lived inside the Park because they were afraid of geysers”. This has now been debunked. In fact, geysers were often considered sacred and worshipped in many indigenous cultures. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Old Faithful Geyser is one of Yellowstone National Park’s biggest attractions and is one of many of the park’s geothermal features. A popular American myth claimed that “Native Americans never lived inside the Park because they were afraid of geysers”. This has now been debunked. In fact, geysers were often considered sacred and worshipped in many indigenous cultures. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Settling in the ‘Wild West’

Post the Civil War (1861-1865), spurred by the development of railways in the American West, white settlers began moving westwards and settling there in hopes of a prosperous future. The settlers soon transformed the land. Huge herds of American bison that once roamed the plains were almost completely wiped out. Farmers ploughed the natural grasses to plant wheat and other crops. There was also a mining boom.

Most importantly, the westward migration ushered in an era of conflict between the settlers and the Native Americans who had lived and ruled over the land for many millennia.

In 1868, President Grant began pursuing a “Peace Policy” which included the goal of relocating various tribes from their ancestral lands to missionary-run Indian reservations. This was, however, far from peaceful; it led to some of the bloodiest fighting between the United States and the Native Americans, including several massacres of Native Americans in the hands of the US Army.

The setting up of Yellowstone National Park, the subsequent removal of the land’s Native American population and the erasure of their history cannot be extricated from the larger story of the colonisation of the American west. The park displaced multiple tribes and denied them of their age-old hunting grounds while at the same time erasing their very existence from public consciousness which, over time, remembered the beauty of the western wilderness rather than the blood spilled to effectively create it.

A 2021 study in the Science journal found that “indigenous people in the United States have lost nearly 99 per cent of the land they historically occupied” through “forced migration”. The consequences of this mass dispossession can be felt in the socio-economic deprivations of Native Americans till date. However, this is seldom spoken out in mainstream US discourse and even when it is, its sheer scale is often underplayed. As recently as 2021, the National Park’s visitor brochure said, “When you watch animals in Yellowstone, you glimpse the world as it was before humans.”

While the history of this dispossession neither begins nor ends with Yellowstone National Park, it no doubt played its part, both in dispossessing and then numbing the public to brutality of this dispossession by creating and sustaining the myth around the West’s “pristine wilderness”.

“When people look at Yellowstone, they should see a landscape rich with Native American history, not a pristine wilderness. They’re driving on roads that were Native American trails. They’re camping where people camped for thousands of years,” Macdonald says, emphasising upon the importance of at the very least acknowledging the terrible cost of creation of Yellowstone National Park.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05