Data show that air pollution levels are high in other months too, even in coastal cities like Mumbai, primarily because of industrial activity and vehicular emissions. But during winters, meteorological factors (wind direction, low temperatures) and certain triggers (farm stubble burning and festive firecrackers) worsen the conditions in cities like Delhi.

In this context, China is often held up as an example worth emulating.

Earlier this month, a spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in India, Yu Jing, stated on social media that “China once struggled with severe smog, too” and that they were ready to share their journey towards blue skies with India.

What exactly were the issues in China? How successful was it in solving them, and can those measures be applied to India?

Behind China’s ‘airpocalypse’

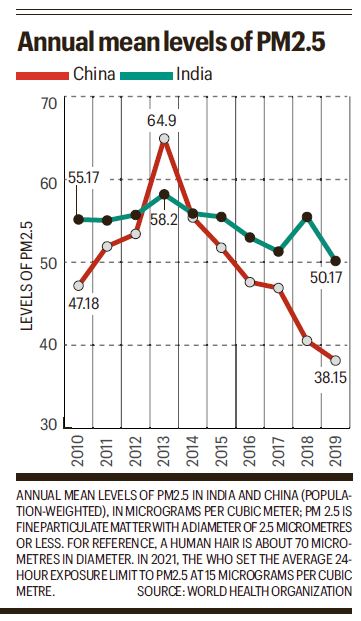

Arideep Mukherjee, a former senior researcher at the Banaras Hindu University and a visiting professor at China’s Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, was a co-author for a 2023 study comparing the countries’ air pollution woes. He told The Indian Express that “India’s current air pollution scenario is comparable to China’s in the late 2000s in terms of high particulate matter concentrations and the significant health and economic burdens associated with it. Both nations share common drivers of pollution, such as rapid development and urbanisation.”

China’s turn towards industrial growth, with economic liberalisation in 1978, led to a manifold rise in carbon emissions. By the 2000s, the byproducts were visible in hazy skies and river pollution, the latter of which led to public protests even under an authoritarian state.

The 2008 Beijing Olympics also raised concerns for the government, with the world’s eyes on the country.

Story continues below this ad

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, in its 2022 Guide to Chinese Climate Policy, noted that the primary air pollutant in China’s urban areas was fine particulate matter, such as PM2.5. It can “penetrate lung tissue, enter the bloodstream and accumulate in the central nervous system… [it] comes from many sources, especially heavy industry, coal burning for heating, vehicle emissions, power plant smokestack emissions, crop burning and fertilizers.”

Since 2013, “almost 80% of China has experienced air quality improvement.”

How China cleared the air, with some caveats

In the late 2000s, air pollution attracted substantial government focus. Alex L Wang, a professor at the UCLA School of Law, wrote in a 2017 paper for Harvard Environmental Law Review that China’s 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–10) mentioned the issue as a concern, and a key method to enforce green norms was “the cadre evaluation system — China’s system for top-down bureaucratic personnel evaluation.”

Here, the organisation departments of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) implement performance targets for officials at various levels, covering governors, mayors, county magistrates, and others. Their performance relative to their peers determines promotions and overall assessments.

This was accompanied by increasing investment in pollution control equipment in industries. “Implementation also relied to a significant degree on shutdowns of outdated industrial capacity designated as excessively polluting or energy consuming (for example, power plants, smelters, chemical facilities, paper plants),” Wang wrote.

Story continues below this ad

The government further pushed for the adoption of Electric Vehicles. The Oxford Guide noted, “Though the majority of China’s electricity comes from coal, carbon emissions from EVs are generally lower on a lifecycle basis than internal combustion vehicles due to the greater efficiency of electric vehicles… (they) do not have tailpipe emissions and the power to recharge them is usually generated outside urban centers”.

Shenzhen, the third-largest city in China, completely electrified its fleet of over 16,000 buses in 2017 — a first in the world. At the time, its population stood at around 11 million, roughly the size of Bengaluru today. Other major cities, such as Shanghai, followed suit.

Researchers at Tsinghua University and the Beijing Environmental Bureau found that between 2013 and 2017, controls on coal boilers (used to generate thermal energy), cleaner residential heating, closure of local emissions-intensive industries and vehicle emissions controls led to air quality improvements (in decreasing order of impact).

However, there is still significant room for improvement.

The top-down implementation pressure can at times result in falsified information and the covert reopening of closed factories by local leaders. And, with recent government commitments to increase coal production capacity in the wake of a 2021 power shortage in some areas, there are concerns about rising levels of PM2.5 and ground-level Ozone. Moreover, China’s base standards for air quality are much lower than its Western counterparts.

Several lessons for India

Story continues below this ad

Both countries introduced environmental legislation in the 1980s, and air quality-focused programmes in the 2010s. However, their trajectories have diverged in terms of effectiveness.

For one, China’s approach was characterised by long-term continuous action. A key policy in India is the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP), which mandates measures like the closure of certain factories but only once a certain level of air quality is breached. It is also more localised, covering only the NCR.

The 2023 comparative study, published in the Environmental Science and Policy journal, zeroed in on two fundamental determinants of success: “whether the country has adequate political will and financial resources to prioritise air quality, and whether the country can develop an accountability mechanism that clearly links top-level air quality standards with facility-level emissions control measures.”

It noted some differences. Unlike China, India must contend with emissions from households, in the form of biomass burnt for fuel in rural areas. The Centre’s LPG subsidy scheme has helped, but the authors wrote that more affordable clean fuel needs to be accessible to the people.

Story continues below this ad

Also, by the time China turned to tackling pollution, most of its people had access to power. It could thus scale back on some power plants and industries, with financial resources at hand. Not only does India face a lack of equitable access to resources such as electricity, but green commitments are often seen as a trade-off with growth.

Then there are the governance systems — China’s unitary setup against India’s tiered governance, where authorities often overlap in jurisdiction and accountability is rarely attached to a particular institution.

This is not to say that India has made no progress. The judiciary, especially, has allowed for various public interest litigations that direct action. The study noted that China would do well to integrate more “Indian-style approaches, in terms of decentralisation and legal accountability.”

Mukherjee stated that given their differences, India adopting some of China’s methods may lead to overall benefits, but it might not exactly mirror its trajectory. India can, however, borrow strategies like controlling industrial and vehicular pollution by implementing stringent emission regulations, expanding the use of cleaner fuels, and promoting public transportation.

Story continues below this ad

“China’s experience shows that comprehensive control measures, informed by robust environmental monitoring and scientific research, can lead to significant improvements in air quality,” Mukherjee said. While acknowledging the need to tailor an India-specific strategy for certain areas, he said, the China scenario “offers valuable lessons”.