Highway to ‘climate hell’: What breaching the 1.5 degree Celsius warming threshold could mean

There is an 80% chance that the world will temporarily cross the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold in the next five years. A long-term breach would accelerate and intensify the catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Residents watch a wildfire burn in California, in 2022. (Reuters/File)

Residents watch a wildfire burn in California, in 2022. (Reuters/File)This May was the warmest May ever. In fact, each of the last 12 months have set a new warming record for that particular month, Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) said last week.

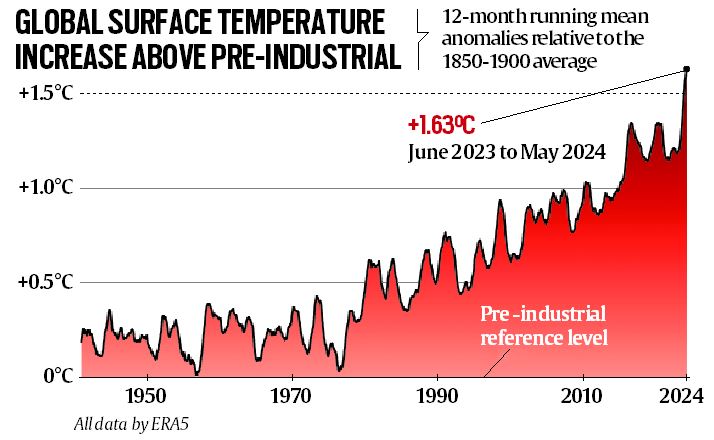

The average global temperature last month was 1.5 degree Celsius above the estimated May average for the 1850-1900 pre-industrial reference period. For the 12-month period (June 2023 – May 2024), the average temperature stood at 1.63 degree Celsius above the 1850-1900 average.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO), in a separate report published on June 6, said there is now an 80% chance that at least one calendar year between 2024 and 2028 would see its average temperature exceed 1.5 degree Celsius above the pre-industrial levels — for the first time in history. Just a year ago, the WMO had predicted a 66% chance of the same.

Scary as these facts are, they do not imply that the world is about to breach the commonly talked about 1.5 degree Celsius temperature threshold. That threshold refers to a warming over a longer period, with usually a two or three decade average taken into consideration.

What is the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold?

In 2015, 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement, which pledged to limit global temperatures to “well below” 2 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. It also said countries would aim to curb warming within the safer 1.5 degree Celsius limit.

While the Agreement did not mention a particular pre-industrial period, climate scientists generally consider 1850 to 1900 as a baseline, since it is the earliest period with reliable, near-global measurements. Some anthropogenic global warming had already taken place at that time — the Industrial Revolution began in England in the mid-1700s. Nonetheless, a reliable baseline is crucial to measure the rising temperatures today.

All data by ERA5

All data by ERA5

Why 1.5 degree Celsius?

The safer 1.5 degree Celsius limit was chosen based on a fact-finding report, which found that breaching the threshold could lead to “some regions and vulnerable ecosystems” facing high risks, over an extended, decades-long period.

The 1.5 degree Celsius was set as a “defence line”, to ensure that the world avoids the disastrous and irreversible adverse effects of climate change which would begin to unfold once the average temperature increases by 2 degree Celsius above the pre-industrial levels. For some regions, even a smaller spike will be catastrophic.

What happens when threshold is breached?

The 1.5 degree Celsius threshold is not a light switch which, if turned on, would trigger a climate apocalypse. It is just that once this threshold is breached for a long period of time, the impact of climate change such as sea level rise, intense floods and droughts, and wildfires will significantly increase and accelerate.

Speaking to MIT News, Sergey Paltsev, deputy director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, said: “The science does not tell us that if, for example, the temperature increase is 1.51 degree Celsius, then it would definitely be the end of the world. Similarly, if the temperature stays at a 1.49 degree increase, it does not mean that we will eliminate all impacts of climate change. What is known: The lower the target for an increase in temperature, the lower the risks of climate impacts.”

The world is already witnessing these consequences, to some extent. For instance, the severe heatwave over North and Central India in late May, which saw temperatures nearing 50 degree Celsius in Delhi and Rajasthan, was nearly 1.5 degree Celsius warmer than past heatwaves. The heatwave reportedly caused hundreds of deaths, and can be attributed to rising global temperatures.

In April, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said the fourth global mass coral bleaching event has been triggered by extraordinarily high ocean temperatures. This could harm ocean life, and the lives of millions of people who rely on reefs for food, jobs, and coastal defence.

Last year, a report found that five major climate tipping points are already at risk of being crossed due to warming. Climate tipping points are critical thresholds beyond which a natural system can tip into an entirely different state. They cause irreversible damage to the planet, including more warming.

Scientists have identified a number of these tipping points across Earth, which fall into three broad categories: cryosphere (for example, melting of the Greenland ice sheet), ocean-atmosphere (change in water temperature), and biosphere (death of coral reefs), according to a report by the European Space Agency (ESA).

How can the world stay within the threshold?

2023 was the warmest calendar year ever recorded. The WMO reported that the average global temperature reached 1.45 degree Celsius above the pre-industrial levels. But the unusually high temperatures were also partly due to the onset of El Niño, an abnormal warming of surface waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. This weather pattern is known to lead to record-breaking surface and ocean temperatures in some parts of the world.

El Niño has now peaked and is likely to transition towards the cooler La Niña in the following months. Nonetheless, the world is most likely to temporarily breach the 1.5 degree Celsius limit in the next five years. Each year between 2024 and 2028 is predicted to be between 1.1 degree Celsius and 1.9 degree Celsius higher than the pre-industrial average, the recent WMO report found.

The only certain way of remaining under the threshold is to immediately, and radically, curb the emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases (GHG). To do this, the world needs to stop burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, which release GHGs into the atmosphere. So far, countries have failed to make a significant dent in this regard.

In 2023, the levels of GHGs in the atmosphere reached historic highs. Carbon dioxide, which is the most abundant anthropogenically produced GHG, rose in 2023 by the third-highest amount in 65 years of recordkeeping, according to NOAA.

As UN Secretary-General António Guterres said on June 5: “We are playing Russian roulette with our planet… We need an exit ramp off the highway to climate hell, and the truth is we have control of the wheel.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05