Two years after Myanmar coup, how the country is a mess — and India’s headache has worsened

In India, which shares a 1,600-km border with Myanmar along four Northeastern states, as well as a maritime boundary in the Bay of Bengal, the failure of the Myanmar state presents a foreign policy dilemma that it is struggling to resolve.

Protesters hold up a picture of Myanmar's army chief Min Aung Hlaing with his face crossed out and pictures of Aung San Suu Kyi, during a demonstration to mark the second anniversary of Myanmar's 2021 military coup, outside the Embassy of Myanmar in Bangkok, Thailand, February 1, 2023. (Reuters Photo: Athit Perawongmetha)

Protesters hold up a picture of Myanmar's army chief Min Aung Hlaing with his face crossed out and pictures of Aung San Suu Kyi, during a demonstration to mark the second anniversary of Myanmar's 2021 military coup, outside the Embassy of Myanmar in Bangkok, Thailand, February 1, 2023. (Reuters Photo: Athit Perawongmetha) It is exactly two years since the Myanmar army seized power. The coup took place in the pre-dawn hours of February 1, 2021, the day on which new Members of Parliament were scheduled to meet in an inaugural session to take the oath of office. The National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi had won a landslide victory. The army, which contested the election through its proxy party, the United Solidarity and Development Party, had fared poorly.

To justify the coup, the generals alleged rigging by the NLD, the ruling party of the previous five years in a hybrid civil-military arrangement with the army, though it appears to have been driven by the fear that Suu Kyi, backed by the democratic parties in Parliament would rewrite the 2008 Constitution and write the military out of it. Within a few hours, the military erased 10 years of a so-called “transition to democracy” and returned the country to 1990.

For the Myanmar military, the plan that did not work out

But how the coup unfolded after 2021 is quite different from the 1990s. The present leadership of the army led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, who heads the junta regime named the State Administration Council, has failed to bring the country under its control. On the ground, hundreds of armed pro-democracy civilian resistance groups (People’s Defence Forces) are fighting the junta and turning swathes of the country into no-go areas for the army. In addition some among the two dozen ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) that have been fighting the Myanmar state for autonomy for the last seven decades, have joined hands with the PDFs.

At the political level, a National Unity Government comprising many of the elected parliamentarians, has fashioned itself as a government in exile, and has been lobbying foreign governments for diplomatic recognition. The junta’s has given a tough military response against the pro-democracy fighters on the ground and EAOs that back them, with land forces and air power. So far, it has failed to force them into submission. The situation is a violent impasse, in which neither side can claim an upper hand.

India’s continuing policy tightrope in Myanmar

In India, which shares a 1,600-km border with Myanmar along four Northeastern states, as well as a maritime boundary in the Bay of Bengal, the failure of the Myanmar state presents a foreign policy dilemma that it is struggling to resolve.

For some three decades, India has pursued a “dual-track policy”, which essentially means doing business with the junta, which has ruled over Myanmar for all but five years since 1990, with tea and sympathy for the pro-democracy forces.

The decision to engage with the military rulers was taken in the mid-1990s primarily as a quid pro quo for its help in securing India’s Northeastern borders by denying safe haven on its soil to Northeastern insurgencies. This worked to India’s advantage, and became the touchstone by which the relationship with military-ruled Myanmar was built for several years. Over the last two decades, as China with its deep pockets emerged as a rival in the region, engaging with the junta was also seen as a way to retain Indian influence in Myanmar.

Myanmar nationals living in Thailand hold portraits of former leader Aung San Suu Kyi during a protest marking the two-year anniversary of the military takeover that ousted her government outside the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand, Wednesday, Feb. 1, 2023. (AP/PTI Photo)

Myanmar nationals living in Thailand hold portraits of former leader Aung San Suu Kyi during a protest marking the two-year anniversary of the military takeover that ousted her government outside the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand, Wednesday, Feb. 1, 2023. (AP/PTI Photo)

Delhi had to calibrate this engagement during the “democratic transition” of the last decade and rebalance the dual track. Now it is back to square 1 again. But as the coup enters its third year in this second decade of the 21st century, the limits of the old template — doing business with the military regime, encouraging it restore democracy, and offering sympathy to democratic forces — are becoming apparent, even going by India’s narrowly defined national interests: border security management, and restricting China in Myanmar.

Five ways in which India’s calculations have been upset

PDFs in the Sagaing region control large parts of the area through which the trilateral highway passes, starting at Tamu checkpost opposite Moreh in Manipur. NUG sources have told The Indian Express that at least on two occasions, its office bearers had to intervene with the local PDF leaders to allow project vehicles to pass.

In the first week of January, Union Minister of Ports, Shipping & Waterways Sarbananda Sonowal said that Sittwe port, developed by India as part of the Kaladan project, was ready for operation. Mizzima, a Myanmar news site, also reported three weeks ago, quoting both the military governor in Rakhine and Indian Embassy sources, that the port, which is situated on the Bay of Bengal at the mouth of the Kaladan river, would be inaugurated “soon”. While India-Myanmar maritime trade was one objective, the primary objective of this project, to provide alternate access to India’s landlocked north-east states, now seems like a bridge too far.

Secondly, the conflict following the coup has spilled over into India. Mizoram is hosting tens of thousands of refugees from the adjoining Chin state in Myanmar. Refugees have come into other Northeastern states, though in fewer numbers. Last month, around 50 Myanmar refugees including some minors were rounded up in Manipur’s border town Moreh and taken to a detention centre. More dangerously, the recent bombing by the Myanmar Air Force of a Chin militia headquarters on the border with Mizoram, with shrapnel hitting the Indian side during this operation, triggered panic in the area.

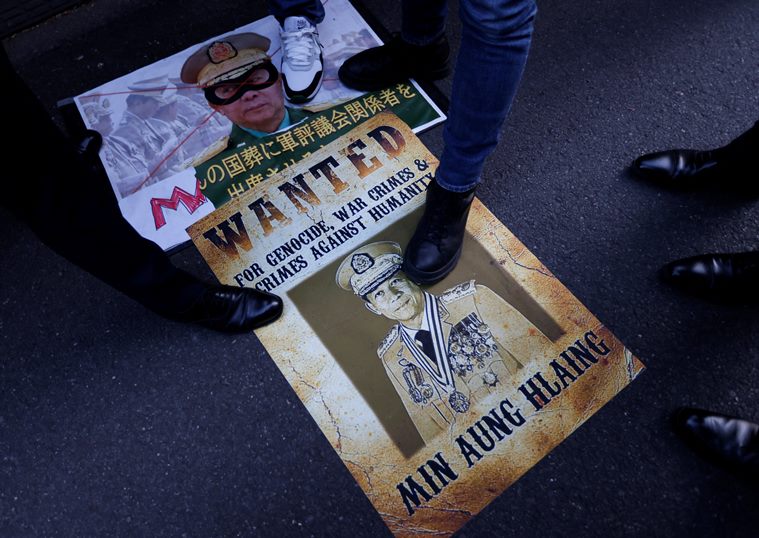

Myanmar protesters residing in Japan step on posters of Myanmar’s army chief Min Aung Hlaing with his face crossed out and ‘Wanted’ message, during a rally to mark the second anniversary of Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, outside the Embassy of Myanmar in Tokyo, Japan February 1, 2023. (Reuters Photo: Issei Kato)

Myanmar protesters residing in Japan step on posters of Myanmar’s army chief Min Aung Hlaing with his face crossed out and ‘Wanted’ message, during a rally to mark the second anniversary of Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, outside the Embassy of Myanmar in Tokyo, Japan February 1, 2023. (Reuters Photo: Issei Kato)

Another potential cross-border spillover is contained in the latest report of the UN Office for Drugs and Crime on Myanmar (Myanmar Opium Survey). The report, covering four states — Shan, Kachin, Kayah and Chin — points to a sharp 33 per cent spike in poppy cultivation in that country. But the sharpest increase has been noticed in Chin state, in an area that borders northern Mizoram and southern Manipur. According to Angshuman Chaudhary, a Myanmar expert and associate fellow at the Centre of Policy Research, the patch coincides with an area in which the Zomi Reunification Organisation, a Myanmar military proxy, is dominant.

Third, the Indian security establishment is aware that the Myanmar junta has recruited Indian insurgent group (IIGs) in regions adjoining Manipur and Nagaland to fight against the local PDFs and other groups, and that rearmed by the junta for this purpose, these groups are now strengthening themselves. Of these groups, the People’s Liberation Army has been held responsible by India for the deadly attack on an Assam Rifles convoy, in which a colonel, his wife and son, and four AR personnel were killed in November 2021.

Fourth, the military cannot resolve the Rohingya crisis, another regional destabiliser.

Fifth, defining national interests more broadly, India itself has changed since the 1990s, and particularly since 2015. It now describes itself as the “mother of democracy” and has projected its year-long presidency of the G20 as an opportunity to project the voice of the global south.

A question that Myanmar’s 54 million population may ask is what can India do in this year for both its democratic and economic aspirations — the junta has not just ended Myanmar’s democratic experiment, but has also killed its economic development over the years. Instead of “waiting and watching” for the situation to develop, could India play an active role.

The options that New Delhi still retains

Myanmar watchers in India, including several former diplomats, believe New Delhi is not without options: it can open channels to the democratic forces and to some ethnic groups; it can work more actively with ASEAN; it could open an army to army channel with the junta; increase people to people channels; offer scholarships to Myanmar students like it did for Afghan students in a different era.

Meanwhile, the junta is mulling elections later this year after rejigging the first-past-the-post system to proportional representation to undermine the NLD’s electoral might. Perhaps the military believes this might make it more acceptable to the international community. But at this point, it seems an election may only worsen Myanmar’s conflict, especially when its most popular leader, the 77-year-old Aung San Suu Kyi, remains imprisoned by a military court on questionable charges.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05