Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

The unheard melody

Ustad Asad Ali Khan was a legendary rudra veena exponent, whose mastery over a difficult, rigid instrument was never documented until filmmaker Renuka George decided to tell his story

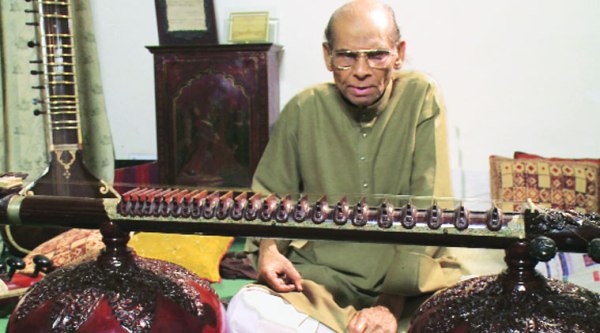

A still of Asad Ali Khan from the film on him

A still of Asad Ali Khan from the film on him

The inward, brooding notes of the rudra veena on raag Gaud Sarang resonate in 97, Asiad Village, Delhi. A thin, small-framed man sits on his knees with a gigantic veena “riding on the body” and moves his hands over 24 wooden frets to put forth a winding melodic structure. The piece moves in a number of directions while leaning on the resting notes— pancham and gandhar at regular intervals. With sweat dripping down his face and neck, he shuts his eyes, and touches a combination of notes in his trademark beenkari style, which surprisingly invokes hope. Strange for a raga that is known to be serious. More so, strange for a raga being played on an instrument such as the rudra veena, known for its contemplative mood.

The musician merges everything together and the result is a hypnotic drone, and then he does that one thing, which musicians strive to achieve their entire life—He makes the raga stand in front of you; as if it was a person. “This is the effect of pure music,” says a choked Asad Ali Khan, as he puts down the veena, and looks away from the camera in Renuka George’s documentary, Asad Ali Khan – A Portrait, which was screened at Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in Delhi on Friday.

Tears never roll down Khan’s eyes, but it isn’t hard to see through his soul in that moment, where years of learning merge into minutes of Gaud Sarang. George’s documentary is a fascinating peep into the world of rudra veena, and Khan, whose life was never documented until George decided to tell this legendary musician’s story. “I always wanted to know what goes on behind the scenes: What runs through an artiste’s mind before he performs, that dedication to one’s art form and the journey to the stage fascinated me. In Khan sahab’s case, the lack of any document on him, further determined me. His dedication to a difficult art form was extremely moving,” says George, who was funded by Edward and Benjamin de Rothschild Foundation and the LODH Bank to create this film.

A graduate from London School of Economics, George spent her childhood all over the world, before spending almost 25 years in France, a country where dhrupad found a lot of attention. She met Khan through Dagar Brothers, names synonymous with dhrupad. Dhrupad is also a genre that is played on the rudra veena and originated from the Vedas.

The film’s narrative begins in Alwar where Khan goes back to his ancestral house, talks about his childhood,one of the oldest Indian instruments, learning from his exacting father Sadiq Ali Khan, a court musician. “Earlier people played for one Nawab. Aaj kal toh sabhi Nawab hain,” says Khan, laughing in the film.

The film journeys through his childhood and early years, full of strict learning of a difficult instrument and follows him to Delhi. With its complex grammar and aesthetics, it is primarily a form of worship. “You have to live the life of an ascetic to master an art form as pure as this,” explains Khan in the film. He never married and passed away in 2011, exactly a year after George shot the film.

Neither George, nor does her voice appear in the documentary which is what has resulted in the narrative to flow. It is also a way through which George has drawn out a reclusive musician to talk. “The pauses you see are important. It is his story. I wanted to be as non-intrusive as possible. I wasn’t looking for scoop. I was looking for him to open up,” says George, who adds that she wanted people to have direct contact with the musician. She is now in talks to release the film as a DVD. George also wants to work on other projects, one of them being a film on TM Krishna, but is bogged down by lack of funds. “Even if I manage to make one more film, I will consider myself lucky,” says the 54-year-old, who also works as a French to English book translator.

Often, in music documentaries, it’s the small things that resonate the most and George makes it a point to depict those beautifully. She finds joy in the mundane, which is what makes the narrative interesting, and provides the film with an integrated wholeness.

A beautiful scene from the film comes after a private concert by Khan in his house. Ustad Fahimuddin Dagar, vocalist LK Pandit and Khan are seen discussing the friendship their fathers and grandfathers shared, and how they were lucky to be born in the times of such legends. “Kya daal banti thi inke ghar,” says Khan looking at Pandit at which the three laugh out loudly with their fake teeth and real smiles which fade into the melodies of the rudra veena.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05