Quentin Tarantino has famously declared that he will retire from filmmaking after directing his 10th movie. He believes that most directors lose their mojo in old age, and as someone so obsessed with leaving behind a perfect filmography, he doesn’t want to take the chance and make a stinker when he’s 75 or something. Of course, there’s some logic to Tarantino’s theory. Because for every Steven Spielberg and Clint Eastwood, there’s a JP Dutta, and more recently, a Sooraj Barjatya.

Although he isn’t as old as he appears — stunningly, Barjatya is the same age as Shah Rukh Khan — he embodies the Bollywood of yore. In fact, he got his start in the same decade as Tarantino. No other Hindi filmmaker is as synonymous with the ‘90s, except perhaps Aditya Chopra (all because they made one movie each that became a cultural landmark). Incidentally, both Barjatya and Chopra are what the kids today would describe as ‘nepo babies’; the filmmakers also recently experienced success, at a time when they had both been written off.

The Romantics, sold as a throwback to the Golden Age of Hindi cinema, turned out to be a glorified orientation video for YRF. But the truth of the matter is that in our country, where money is almost always equated with success, nobody questions the creative worth of films like Neal ‘n’ Nikki and Thugs of Hindostan when trade analysts are trumpeting hourly box office figures of Pathaan from the parapet. It’s a good film, sure, brilliant even, in parts; but also very derivative. Fortunes really do turn after every Friday in Bollywood.

A similar story unfolded last year, when Barjatya’s Uunchai — one of the most bizarrely inept and outdated Hindi movies in recent memory — became a surprise box office hit. But the film’s success barely had anything to do with its quality; what should be studied and celebrated instead is the film’s clever release strategy, incidentally orchestrated by YRF. Uunchai debuted in limited theatres — a proven method abroad — and relied on its target audience to show up to theatres. The film’s core demographic — old people — would have had little interest in Ek Villain Returns or Heropanti 2, but they quickly recognised Uunchai as the year’s sole Hindi movie that appeared to speak to them and their anxieties. Barjatya simply exploited a market that had been severely underserved, especially in the pandemic.

Funnily enough, this is the same distribution tactic that horror specialist studios have been using for years. But more specifically, smart studio filmmaking like this is how you get two Best Exotic Marigold Hotel movies (combined gross of over $200 million), two Book Club movies (the first one made more than $100 million and the second is around the corner), and more recently, A Man Called Otto ($100 million).

For Uunchai to have made money is surprising enough, but for it to have made money despite being so uniformly terrible is what’s so shocking. Emotionally manipulative, cheap-looking, and mind-numblingly long, the film doesn’t have a single scene that feels real. Every moment, every exchange, every line of dialogue feels like it was coughed up by the human equivalent of Bing, while being held prisoner in the Rajshri basement. Uunchai’s thematic inauthenticity can only be rivalled by its visibly artificial backdrops.

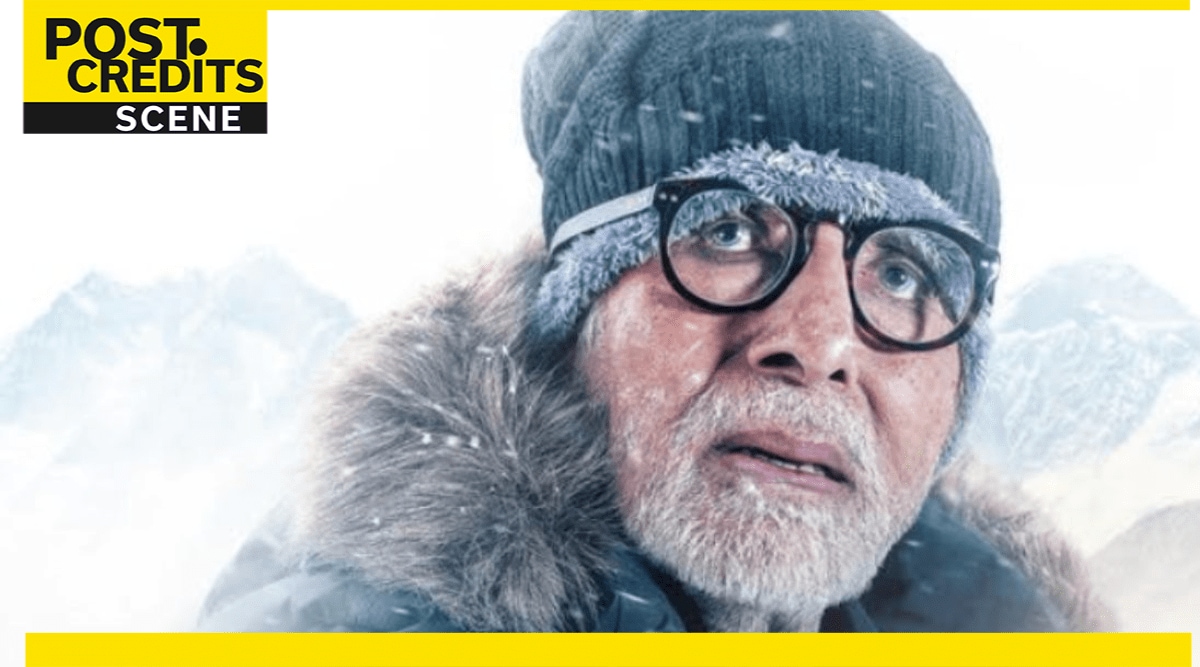

Amitabh Bachchan, Anupam Kher and Boman Irani star as old friends who decide after a cringe dance sequence (which may or may not have triggered their buddy’s death) that they should trek to the Everest Base Camp. Along the way, they take brief detours into Baghban and Black territory, and are forced to contend not only with age-related ailments, but four women who are painted as villains for no apparent reason. No kidding; the movie practically contorts itself to present its female characters as negative — they’re either nags, heart-breakers, or hurdles. But Barjatya’s closet misogyny deserves a separate article.

Story continues below this ad

But let’s talk about something less uncomfortable, but almost as unforgivable — tacky filmmaking. The manipulative tone aside, it’s a little ironic for a movie that celebrates the spirit of the elderly to not demand that its biggest star be present at actual shooting locations. Not only does it often seem like Bachchan is wearing his own wardrobe — I briefly wondered if the movie was shot in Jalsa — he is conspicuously absent from every mid-shot and close-up in the trekking scenes. The wide shots all use a body double, while any shot that requires a clear look at his face gives strong Headlines Today weather report circa 2005 energy.

In the highway driving sequences, which were all shot in-studio except the second unit stuff, the windows of their car open and close depending on whether Barjatya wants a close up or a long shot, because God forbid glass obscures our view of Anupam Kher. Forget dirtying the frame to add character, this approach embodies everything that is wrong with this film; it’s too sanitised — emotionally, visually, thematically.

But nothing is as spectacularly bad as the moment where Bachchan’s character, Amit, has the sudden urge to visit the Taj Mahal after spotting a miniature model at a restaurant, in Agra. Did he forget that the Taj is in Agra? Why did Barjatya feel the need to give him a visual trigger to remind him that it is? It boggles the mind. And when Amit actually goes to the Taj, it’s all filmed against a green screen, of course.

The odd thing is that none of this decidedly amateurish filmmaking has appeared to have annoyed anybody. Uunchai’s success and the failure of movies like Shamshera and Cirkus, purportedly because of evolving audience tastes, should be discussed in the same conversation — both are a marker of just how badly mainstream film culture has declined. How else would we have found ourselves in a position where something as overtly corporate-driven as The Romantics is praised and genuinely wonderful Hindi movies continue to be overlooked?

Story continues below this ad

Only when this self-congratulatory phase ends will Bollywood truly witness a creative overhaul. There’s a reason why the mainstream Hindi film industry discards directors so frequently. Old sensibilities are blamed, as are the changing tastes of audiences. But these are just excuses; this happens mainly because in India, we don’t make movies, we make products that nakedly pander to the majority. Which is why barely any old blockbuster from even a couple of decades ago — including Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge and Hum Aapke Hain Koun — holds up to scrutiny today. Mainstream Bollywood rarely produces timeless entertainment; consuming them after their use-by date could be dangerous.

Post Credits Scene is a column in which we dissect new releases every week, with particular focus on context, craft, and characters. Because there’s always something to fixate about once the dust has settled.