Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

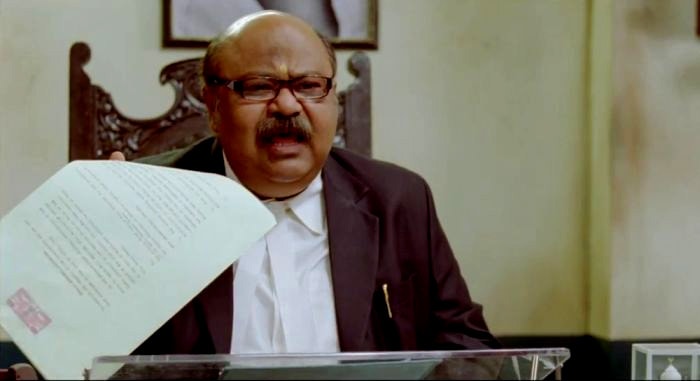

In India, we don’t critique, we criticise: Jolly LLB 2 actor Saurabh Shukla

One of Bollywood’s most experienced character actors, Saurabh Shukla on his latest role in Jolly LLB 2, being a reluctant actor and why it’s a good time to be a filmmaker in Bollywood.

Jolly LLB 2 actor Saurabh Shukla talks on critique and criticism.

Jolly LLB 2 actor Saurabh Shukla talks on critique and criticism.

The verdict is that the sequel outdoes Jolly LLB. But, if you look at the skeleton of the story, the format remains the same — of a flawed hero who has a change of heart and takes on the system. It could have easily been repetitive.

What, then, made you sign up for the film?

Subhash Kapoor, the director, and I, were both averse to the idea of a sequel because, as you say, it follows an inherent formula. But it’s a classic format and, I suppose, Subhash realised the format won’t change but a lot is left to say. It’s not just the plot that says everything. Each installment of the Rocky series, for instance, follows the same pattern where he falls before winning at the end. What makes each film different is the complexity of the character or the situation it deals with in that particular film. We saw the same potential in Jolly LLB 2.

WATCH VIDEO | Akshay Kumar, Twinkle Khanna’s Valentine’s Day Party

Please elaborate.

The film effortlessly touches upon several issues without steering away from the story or the script. For instance, the reference to the fact that the Supreme Court will have a hearing in the middle of the night for special cases, as it did in the Yakub Memon case, or the scene where Jolly (Akshay Kumar) is shown cooking for his family. They don’t get into their relationship to focus on their equation but it’s presented by-the-way while Jolly and his wife Pushpa (Huma Qureshi) discuss the case. Literature isn’t mere storytelling but also gives a sense of time and place. And cinema — a form of literature today — should also do so. Jolly LLB succeeds in capturing the times we live in through these small touches.

To touch upon so many issues also bears the potential risk of making it clumsy. How difficult was it to deal with that aspect?

Nuanced work can easily go wrong even if the maker has his or her soul in the right place. But, one cannot master this unless one tries. So, the solution is not in avoiding it. In the industry, people keep telling you not to make such films and they blame it on the audience — that they won’t get it. Even the media is partly responsible for this phenomenon. Internationally, if you show your film at a festival and a journalist wants to ask you a question, he will first congratulate you and mention the merits of the film before talking about what he disagrees with. In India, we don’t critique, we criticise, which breaks a maker’s spirit. We are punished for being filmmakers.

Also read | Jolly LLB 2 box office collection day 9: Akshay Kumar film stays strong despite new releases

WATCH VIDEO | Jolly LLB 2: Arshad Warsi, Akshay Kumar Have Jolly Good Time

Yours is the only character from the first film. What was in the film for you to want to take it up again?

There’s also Sanjay Mishra’s character. In the first part, he was the hawaldar who helps Jolly. In the sequel, he was moved to Varanasi and helps this Jolly with evidence. My character is ideologically the same, I agree, but there are changes. Now, he is older, a heart patient, and he has seen more life. For instance, in the first part, when Boman Irani’s character Rajpal screams in the court, my character, Judge Tripathi, screams back and threatens to smash his head. In Jolly LLB 2, he is more patient. When Annu Kapoor’s character, advocate Mathur sits on a dharna in the court to provoke him, he doesn’t file a contempt of court case against him. He understands that the idea is to derail the case but deals with it by also sitting on a dharna to oppose Mathur’s dharna. In the end, he makes sure that the statement of the most important witness is recorded.

The only aspect that the critics seem to mind is the monologues at the end. Do you think they were necessary?

The monologues sum up the film and, critics apart, they seem to have met with audience approval — people in the theatres have been applauding the scenes. The monologue by Mathur raises a question and the one by Jolly is meant to show the mirror and debunk Mathur’s argument. The one by me tries to keep hope in the judicial system alive. If not articulated, people will walk out of the theatre thinking that the hero won. However, it is not the hero who won but his faith in the system. Also, let us not forget this is India, we are verbose people. In European cinema, a similar story would have a lot more silences because they do not talk so much and there aren’t so many people. But Indians like to talk and listen.

Was there any reluctance to work with Kapoor since he has been accused of molestation?

Personally, I think he is decent. Professionally, I’ll say the case is subjudice and he should not be pronounced guilty before the court announces its verdict. The film has some fine performances by noted character actors.

More from the world of Entertainment:

How was it working with that ensemble with Akshay Kumar in their midst?

If you look at his recent choices, like Special 26 or Airlift, it is clear that Akshay is working towards building himself as an ‘actor’ who is also a ‘star’. I was amazed by him because he knew the entire script but never fiddled with it even though he knew there are many long and prominent scenes where Mathur and Tripathi engage, while he isn’t even in the frame. But he didn’t attempt to hog that space.

One of your early films, Satya, also had a strong ensemble, and launched the careers of many big names today. How do you feel about being a part of it when you look back today?

It came at the right time and helped create a faith in the possibilities of storytelling and actors who weren’t stars. The avenues for us were limited but Satya created a space for actors like me who were just starting out. It was brilliant for its time. So many of us who worked on the film, including Manoj Bajpai, Anurag Kashyap and me, were all new. We managed to surprise everyone. I know that if I had to play Kallu Mama today, I’d probably do a better job but for its time, Satya stands out.

When you joined the industry after working with the National School of Drama’s (NSD) repertory, did you know that the avenues were limited?

Well, I didn’t come here wanting to be an actor. A dear friend, the director Sudhir Mishra says I am a reluctant actor, which, perhaps, helps me to not overdo things or carry the anxiety of what will become of me as an actor if the door is shut on me someday. I came to Bombay wanting to make films. Unfortunately, I have not reached the point where I can easily put things together. People get me to write, which is great, because one cannot be an actor or a director unless one writes. It gives you a sense of layering and helps you understand the craft better.

How did acting happen to you then?

By accident. In college in New Delhi, I was filling in for an actor who couldn’t make it. People liked me and I liked myself. But I didn’t take it seriously until I joined the repertory. I needed to make money but NSD doesn’t have a permanent post of director.So I joined as an actor. Shekhar Kapur cast me for Bandit Queen and that’s where my acting career took off. But I don’t do too many films as my focus continues to be writing and directing. I have enjoyed penning Satya, Raghu Romeo, Mithya and so many other films.

You also juggle theatre alongside acting, writing and directing.

Yes, but theatre isn’t my first love. In class six, I told my friends I will one day make a film. I conned them into believing that if you click enough still pictures and run them on a projector, it plays as a film. Making a film remained a dream, and, in college, a friend told me I should not wait till I could direct and begin with theatre instead. He pointed out that theatre has everything film does, except the camera. When I started to do theatre, I fell in love with the medium.

Also read: Jolly LLB 2 movie review : Akshay Kumar, Saurabh Shukla make this an unalloyed delight

In Indian cinema, an overweight man is often used as a trope for comedy. How do you deal with that?

Comedy is a great tool to address dark subjects. But what you speak of is common in slapstick comedy. Someone told me the word ‘slapstick’ has its origins in the British army. The soldiers would get slapped by a stick on the backside if they faltered, which would make them jump and make faces. It’s a very physical form of comedy, which I don’t enjoy. Maybe, I am too lazy for it. It also doesn’t allow layering in a character. So, I simply refuse such roles when they come to me. Judge Tripathi is a good example of the kind of comedy I enjoy. He isn’t trying to be funny. His situation makes him funny. He is a busy judge with responsibilities of his daughter’s upcoming wedding. He multitasks at work like any of us, but, in this case, it requires a judge proofing his daughter’s wedding invite while he attends the court hearing in a murder case. That’s what makes it funny, not the overweight judge.

You have over two decades of industry experience. You’ve seen the industry change and transform. How do you view the current times?

We are in a time where the industry is confused between commercial and indie cinema. This confusion is good for us. Because we don’t know what works, it is creating a space for filmmakers to experiment. Some films, like Jolly LLB or Dangal, attempt to bridge the gap, say what they want to in the commercial idiom. The other advantage is that it has brought homegrown stories to the fore. We aren’t looking towards Iran or Europe for imagery, nor are we looking at Hollywood for themes. Films like Paan Singh Tomar, Dangal, even Sultan, are stories rooted in our land and its people.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05