In Ajnala, a reminder of dark days, rise of another ideologue, and a warning

“SGPC (Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee) and Akal Takht should have condemned the use of Guru Granth Sahib in the protest, but we are yet to hear anything."

For those who have lived through the years of militancy in Punjab, the Ajnala incident raked up memories best forgotten.

For those who have lived through the years of militancy in Punjab, the Ajnala incident raked up memories best forgotten. For those who have lived through the years of militancy in Punjab, the Ajnala incident raked up memories best forgotten. There was déjà vu as sword-wielding youngsters ran amok and their leader, Amritpal Singh, a self-styled preacher who seemed like another polarising ideologue from the distant past, justified the action. Though militancy was officially declared over in Punjab in 1995, its scars remain.

Saying that no two situations are the same, Kanwar Sandhu, former AAP MLA and an editor who had reported on those tumultuous years in Punjab, couldn’t but notice the “unfortunate similarities”. “The runup to Operation Bluestar in 1984 was marked by the same kind of dithering by the administration, people were picked up and then released after pressure.’’

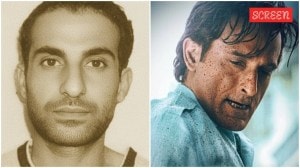

A figure who loomed large over the initial years of turmoil was that of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, head of the Sikh seminary Damdami Taksal. Amritpal Singh, who heads Waris Punjab De, an outfit whose followers stormed the police station, has been fashioning himself after the late ideologue, dressing up and talking like him. “He even wears a pistol around his waist just like Bhindranwale,” says Kanwar Sandhu. But unlike Amritpal, Bhindranwale did not emerge overnight. Nor did he clash with the state in his initial years.

Jagroop Singh Sekhon, a political scientist and co-author of a book on militancy — ‘Terrorism in Punjab: Understanding the grassroots reality’ — recounts how Bhindranwale first clashed with Nirankaris, followers of a religious sect, in 1978. “The confrontation with the state came much later. Amritpal has taken on the state, for the police station implements the will of the state. How did he dare to do it? How did he become larger than life in such a short span?”

These are the very questions that were faced by Bhindranwale too. In the initial years, there was speculation about his political masters. It’s the same with Amritpal. Who is behind his meteoric rise is a question that begs an answer.

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale standing in front of a fortification on Guru Ram Das Sarai before Operation Blue Star commenced. (Express Photo by Swadesh Talwar)

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale standing in front of a fortification on Guru Ram Das Sarai before Operation Blue Star commenced. (Express Photo by Swadesh Talwar)

Kanwar Sandhu rues that then, as now, the clergy, which should have spoken up against the abuse of religion, remained quiet. “The SGPC (Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee) and the Akal Takht should have condemned the use of Guru Granth Sahib in the protest at Ajnala, but we are yet to hear anything.”

But that is where the similarities end. Amandeep Sandhu, author of “Panjab, journeys through faultlines” — an omnibus on the state and its tryst with violence — says times have changed. “When militancy took root in Punjab in the early 1980s, the Sikh sense of faith in the gurdwara hadn’t warmed up to democracy. Now we have seen degradation of gurdwaras, we have seen use and abuse of religion. We suffered a heavy loss of life during militancy. And there was this realisation that in any armed battle against the state, the loss will be of the people. Punjab has understood that we won farmer agitation non-violently, the gurdwara movement and Punjabi Suba movements too were non-violent; violence does not pay.”

Sekhon, who studied the genesis of militancy in Punjab, agrees that the ground situation is different today. “In those days, the factors that spurred militancy included extreme disparity in the rural society after the green revolution, divide-and-rule policy followed by the Centre, the increasingly powerful Leftist movement in the 1970s, and a porous border without any fence.”

Kanwar Sandhu says his feeling is that things will not play out the same way. “Operation Bluestar was totally different from Black Thunder”.

But everyone agrees that there is cause for concern, and the situation should not be allowed to go out of hand. Dr Pramod Kumar of the Institute for Development Communication, warns that there are over two dozen spots that are considered radicalised in the state. “The leadership which does not have a sense of history or vision for the future could aggravate the crisis. There is a need for conflict resolution.”

Kanwar Sandhu rues that Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann continues to hold the Home portfolio, and the state hasn’t had a permanent DGP for the last six months.

Ashutosh Kumar, a political scientist and expert on Akali Dal and gurdwara politics, says he is worried that if not handled sensitively yet strongly, the situation could snowball. “There are youngsters who are seeking a sense of purpose. They have little education, no jobs or future. The government must act swiftly to prevent them from becoming a fodder for inimical elements.”