June 1984 was a landmark month in the history of modern Punjab. As the Indian military, under the orders of then prime minister Indira Gandhi, surrounded the Golden Temple complex in Amritsar to flush out militants who had taken refuge there, the fate of Punjab was being rewritten. Civil rights activist Inderjit Singh Jaijee, and former journalist Dona Suri, in their most recent book, ‘The legacy of militancy in Punjab: Long road to ‘normalcy’,’ published by SAGE have done a microscopic examination of the 36 years that followed ‘Operation Blue Star’.

“Thirty five years ago, one turned on the television or picked up the newspaper to find any number of ‘talking heads’ declaring that India is fighting a civil war in Punjab,” they write, describing the atmosphere of suspicion and armed surveillance that prevailed in the Punjab of 1980s. Things began to change from the mid 1990s as a semblance of ‘normalcy’ was being talked about. ‘Normalcy’ though, as the writers suggest, is a comforting word, far from the truth of the situation. The history of Punjab since 1984 is selectively ‘remembered and forgotten’ they write.

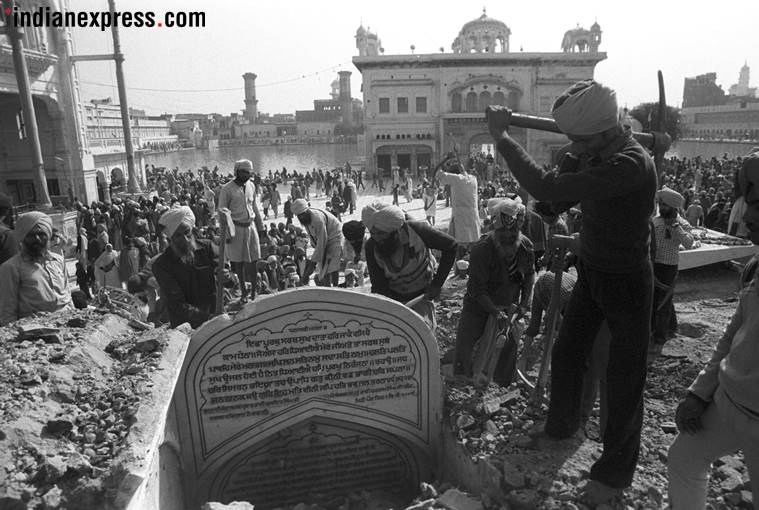

Kar Sevaks pulling down the Akal Takht building built under the supervision of Nihang chief, Baba Santa Singh. Express archive photo by Swadesh Talwar

Kar Sevaks pulling down the Akal Takht building built under the supervision of Nihang chief, Baba Santa Singh. Express archive photo by Swadesh Talwar

In six chapters, the authors dig out minute details of how the state’s economy, politics, culture, and psychology have been impacted by Operation Blue Star, and its selective historicisation. In an email interview with Indianexpress.com, Jaijee and Suri speak about some of the findings in their book.

In the preface of the book, you write that ‘the question of remembering and forgetting underlies our examination of post-militancy Punjab’. How would you say this selective historicisation of 1984 has impacted development, education and employment in today’s Punjab?

Impact can be difficult to measure.

Anybody can make an impressionist assertion – but can they back it up? Punjab’s economic statistics provide hard numbers and each year’s economic record tells a tale. A NITI Aayog report, Fiscal Scenario in Punjab, published in 2018, goes into detail regarding what it calls chronic and alarming debt that cripples the state. What debt? This is debt that the Centre says Punjab incurred as the cost of anti-terrorist operations. Since the ‘90s the Punjab has been paying annual interest to the Centre of more than Rs 5,000 crore in debt-servicing. With that level of outgo, what is left to spend on development of infrastructure and the human capital of the state? Punjab’s downward spiral began in the 90s and has gotten progressively worse.

Another issue is the attitude of the citizens. In 2018 the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Lokniti Programme for Comparative Democracy and Tata Trust, conducted an all-India survey of people’s attitudes toward and perception of the police in their states.

The report found that in Punjab, people’s attitude toward the police is highly negative and highly fearful. Punjab ranked at the top of the list when it came to people’s fear of the police. The report conceded “a possible connection to the particular history of Punjab in the last four decades”.

Story continues below this ad

The average young man, or woman, in Punjab may have trouble articulating their situation, but they know what they are experiencing: stagnant economy, deep trouble in agriculture, symptomised by an appalling number of rural suicides every year, collapse of industry, no jobs and no hope of jobs. They are desperate to migrate anywhere. Drive through even a small town in Punjab and you will see boards advertising IELTS coaching and immigration consultants.

Successive state governments have come in on big talk but either because of indifference or inability, the state has not been able to pull out of its downward spiral. Parties woo the voters with solemn oaths to provide corruption-free and efficient governance; they promise to rescue agriculture and revive the villages, they commit to attracting industry and creating jobs.

If the claims were believed, would lakhs of young people and their parents make a heroic effort to get out of Punjab, out of India? It must also be pointed out that the politicians of Punjab send their own children abroad, which strongly suggests that they do not believe what they say either.

How would you say that 1984 was similar or different from 1947 in terms of its impact on the society, economy, and politics of present day Punjab?

Political developments always have two aspects – one is the rhetoric with which political actors cloak their manoeuvres and the second is the objective environment in which events take place.

Story continues below this ad

Rhetoric changed very little between 1947 and 1984. In 1947 religious sentiments were whipped up: British, Congress and Muslim League — all saw gain in heightening the climate of fear and posing themselves as the ordinary man’s sole hope. In 1987, rhetoric initially focused on economic and state’s rights issues – for example river waters – but as the “gloves came off”, religious manipulation again took over and all the old bogeys were trotted out – discrimination, disintegration, Pakistan. In terms of objective environments, history never repeats itself exactly.

Looking just at Punjab in 1947, the decisive hand then was that of an external political actor — Britain. Punjab Provincial Assembly poll of 1946: The Muslim League’s sole issue was Islamic Punjab; Congress leaders vowed autonomy for Punjab once India became independent — an assurance forgotten once power was transferred. Despite the fact that about 54 per cent of United Punjab’s population was Muslim, the Muslim League was defeated. The middle-of-the-road Unionist Party was shaken but held on thanks to alliance with the Congress and Akalis. Internal politics of Punjab did not force a crisis.

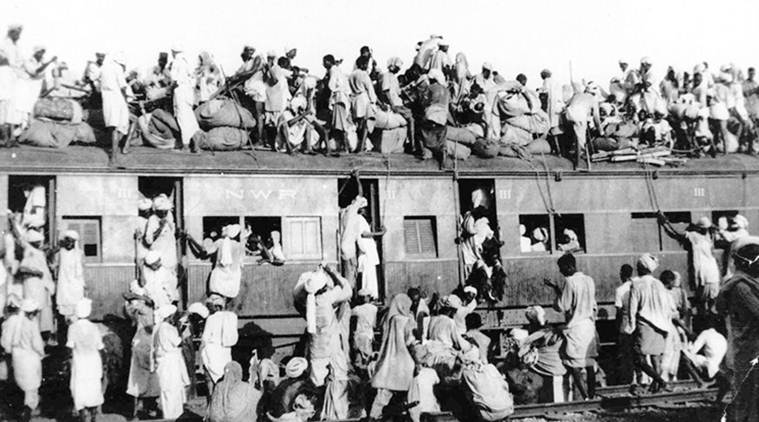

“In 1947 religious sentiments were whipped up: British, Congress and Muslim League — all saw gain in heightening the climate of fear and posing themselves as the ordinary man’s sole hope.” (Express Archives)

“In 1947 religious sentiments were whipped up: British, Congress and Muslim League — all saw gain in heightening the climate of fear and posing themselves as the ordinary man’s sole hope.” (Express Archives)

More than five lakh Punjabis – chiefly Muslim Punjabis and Sikh Punjabis — fought for Britain in the Second World War. Punjab was rewarded with partition and a million deaths. In their eagerness to cut a deal, a war-depleted, bankrupt British government and the Congress sacrificed Punjab’s interests – and set at nought the will of the state’s people expressed by the Assembly poll result – by bowing to the demand of the Muslim League.

Death toll and economic loss were great in the decade of the 1980s but greater still in 1947.

Story continues below this ad

A foreign nation can’t be blamed for what happened in the ‘80s. Punjab’s political leaders and institutions of the state enjoyed a high degree of public confidence in the two decades that followed independence. The ‘60s and ‘70s were decades of rising incomes – from agricultural and small-scale enterprises. Though 1984 is always mentioned as the crisis year, in fact trouble was brewing by the end of the ‘70s. Developments of the period from about 1990 up to the present is what legacy of militancy is all about. This answer is already quite lengthy. In terms of every facet of the state – the police, the administration, the police and legal system, parties and politicians — the era of militancy produced a distrust far more pervasive and lasting than the bloody events of 1947.

You write that ‘people who lived in Punjab observed that Khalistan was finished by 1991 or 1992’, and yet there are several occasions till about last year the Khalistan issue has come up in political discourse. Are you saying that the issue is more of a political imagination? If so, why has that happened?

We combed through about 30 years of newspapers and magazines in search of reports claiming “Khalistan resurgence” in Punjab. In some years we found only two or three such reports, but in the months preceding elections at either the Centre or Punjab, reports were frequent. It was like the call of the cuckoo heralding approaching rain. For example, before the 2019 general election even Army Chief Bipin Rawat was issuing warnings.

Why was this so? Put yourself in the shoes of a political leader. Leaders of out-of-power parties can say or do anything, but people have expectations from a party in power. Vast inequality characterises the distribution of wealth in India. A handful of plutocrats spend crores on children’s weddings while approximately 812 million people earn less than Rs 7,000 a month. Those 812 million are patient but …every five years they vote.

How to get their votes and gain power or remain in power without deflating the top or improving the condition of the bottom? A solution to this difficult problem requires a lot of political imagination.

Story continues below this ad

Fear/hatred is a centuries-old political tool, but still good. If you can whip up enough fear, people forget personal suffering or at least they get someone else to hate besides the political leader.

Civil rights activist Inderjit Singh Jaijee, and former journalist Dona Suri, in their most recent book, ‘The legacy of militancy in Punjab: Long road to ‘normalcy’,’ published by SAGE have done a microscopic examination of the 36 years that followed ‘Operation Blue Star’. (Source: SAGE publications and Pixabay)

Civil rights activist Inderjit Singh Jaijee, and former journalist Dona Suri, in their most recent book, ‘The legacy of militancy in Punjab: Long road to ‘normalcy’,’ published by SAGE have done a microscopic examination of the 36 years that followed ‘Operation Blue Star’. (Source: SAGE publications and Pixabay)

Kar Sevaks pulling down the Akal Takht building built under the supervision of Nihang chief, Baba Santa Singh. Express archive photo by Swadesh Talwar

Kar Sevaks pulling down the Akal Takht building built under the supervision of Nihang chief, Baba Santa Singh. Express archive photo by Swadesh Talwar “In 1947 religious sentiments were whipped up: British, Congress and Muslim League — all saw gain in heightening the climate of fear and posing themselves as the ordinary man’s sole hope.” (Express Archives)

“In 1947 religious sentiments were whipped up: British, Congress and Muslim League — all saw gain in heightening the climate of fear and posing themselves as the ordinary man’s sole hope.” (Express Archives)