Prakash Padukone, the great and the Danes

After a recent visit to Denmark Shivani Naik traces the memorable outing of Prakash Padukone who left a lasting impact.

In Denmark, while playing for Hvidovre Club, Prakash Padukone and Morten Frost practised together and became friends. Eventually the Dane’s game was influenced by the touch-play of the Indian.

In Denmark, while playing for Hvidovre Club, Prakash Padukone and Morten Frost practised together and became friends. Eventually the Dane’s game was influenced by the touch-play of the Indian.

During the early 1980s, as the Chinese onslaught began in badminton, Denmark – the European powerhouse – and Prakash Padukone cozied up to find an answer to the imminent challenge. After a recent visit to the Nordic country Shivani Naik traces the memorable outing of the Indian star who left a lasting impact

It was the early 80s in the Nordic neighbourhood. The Danes were poking fun at the Swedes, though with a wicked twist. ‘You have the best music in ABBA, the best tennis player in Borg and the best car in the Saab,’ they would deadpan, before gloating with a wink and a cackle: ‘But, we have the best beer in Carlsberg!’

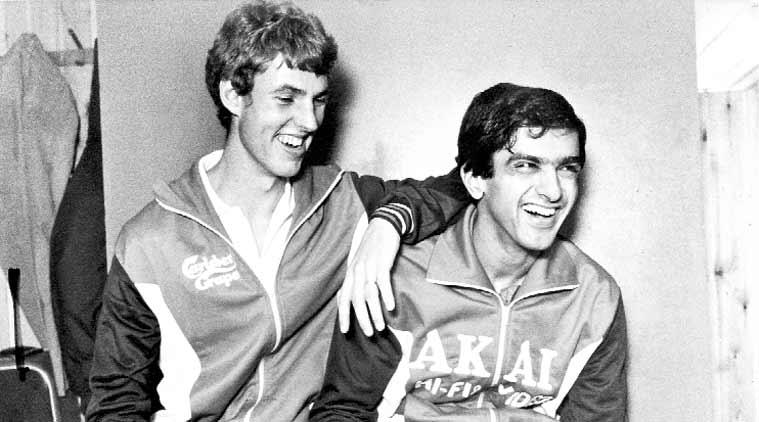

This clever advertising campaign would make the tall Danes — guzzling their local bitter, but with sobriety and humour intact — holler even louder. It was amidst this creative revelry that an Indian, not particularly short himself, would go up on a Copenhagen billboard. The first for an Indian badminton player, Prakash Padukone would be atop a street hoarding for Akai hi-fi sound and video systems. Their mirth directed at the Swedes on other fronts, the Danes weren’t quite proclaiming they had the world’s best shuttler in Morten Frost — though that would follow in some years.

But they were welcoming Padukone to their capital where the soft-spoken Indian with a deceptively sharp game, would join Hvidovre club in the capital’s suburbs and his life-size cut-outs would spring up.

Old Danish players who watched this gentle, suave foreigner drop anchor for six years in their country, recall how the badminton-loving Danes viewed this development. There was talk of Padukone’s ‘hypnotic gaze’ that lasted long, and served as a muttering excuse for whichever player that lost that day, to stomp off.

Prakash Padukone with trainer Svend Carlssen.

Prakash Padukone with trainer Svend Carlssen.

“He was just very reticent outside, and very focussed on court. But, striking eyes. It suited us to make stories of hypnotism from the exotic east while he smashed some of our players,” former doubles world champion Steen Fladberg, says. Some of them recall how a visiting English coach to Denmark ensured Padukone would stay put in the change-room while he gathered a crowd of sweaty players to inspect how the Indian’s kitbag was meticulous.

“It was fiendishly organised. Everything in compartments, nothing out of place. Us players, we would just dump it all in, zip up the bag and rummage through it next day. He was a fascinating foreigner who had come to Denmark,” another adds recalling that December 35 years ago.

Denmark’s across the channel from England, the only other European country to start big on badminton. It gets brutishly cold in this Scandinavian corner and the Danes who are normally jogging and cycling and swimming away their leisure hours, find cosy indoors to play their favourite racquet sport.

It’s the No. 4 sport in the country — behind the usual football, Olympic success story handball and sailing — but the country has the most robust of systems for shuttle – a staggering 600 clubs, ready access to courts and coaching and an endless supply of champions, hence role models.

In the 80s, even as Indonesian great Rudy Hartono was winding down on his all-conquering career and the Chinese had begun swamping the circuit threatening to push everyone out of competition, Prakash Padukone was successfully resisting this onslaught. The Danes who had their own share of champs would be searching for answers of their own, and invite Padukone to their famous Danish badminton league.

Prakash Padukone with Finn Jacobsen, his manager.

Prakash Padukone with Finn Jacobsen, his manager.

India wasn’t quite the far east of shuttle, but a bridge enough to crack the puzzle of the common foe — the Chinese and Indonesians. Frost and Padukone would strike up a friendship soon enough.

The Danes pack stadiums with discerning spectators who come looking for wristy deception as much as the slugging shoulder that smashes like a whip. It is what made the country slowly fall for Prakash Padukone in the 80s. “He was really elegant. I remember many of his matches against Morten Frost,” says Klaus Andreassen, a former player, now with the federation. “He was one of first foreign players who stayed here. Earlier the only foreigners we had in badminton were Dutch women married to our Danes. He came here for sparring because he was defying Chinese and Indonesians, and I’m sure both sides learnt a lot,” he says.

***

The way Prakash Padukone recalls that Indian autumn in the Bangalore of 1980 was his own respectful defiance of what aggravated his parents’ annoyance. At 25, Padukone was one of the youngest senior officers at the Union bank of India after two back-to-back promotions, post his Commonwealth Games (1978 Edmonton) and All England (1980) successes. “My parents were completely against me jetting off to Denmark leaving a very secure job. We were a middle class family and after those two promotions I was one of the youngest officers. Why do you want to give up that security, they kept asking,” he recalls.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained. “I took a big risk because it was then only a 1-year contract. But I was adamant,” he says.

Badminton had gone professional in 1979, and after he won the 1980 Danish Open (as part of the Grand Slam — All England, Danish and Swedish Opens), president of the Hvidovre Club in Copenhagen Finn Jacobsen had approached Padukone to play for the club in the league. “The game had gone open. And I was looking for something after being a 9-time National champion. It was a risk but if I did well, the contract would be extended. I was pleasantly surprised when the bank gave me a three-month leave without pay and were encouraging,” he remembers.

Still, despite the warmest welcomes rolled out for him at Copenhagen, the first biting whip of cold deep in December would pierce through his bones. “It was very different,” he says, recalling the bitter shiver. “I came from a joint family, and from there to being alone with no cooking and the extreme weather. Even the training was different.” At minus 10 to minus 15 degrees, his plans to hit the training running went for a toss. “And there was nobody to talk to,” he says, a quiet soul feeling the sudden prick of silence. Unless there’s a rockshow underway, the Scandinavians are obsessive about silence and quiet — on the streets and indoors and post 6 pm, it’s the unspoken decision, to never din: the hotel reception can turn down a persistent bell that trills off on a busy day when the door would swing back and forth. Six weeks worth Danish classes eased the craving for communication, but there was nothing even remotely akin to the serene chatter of far-off Bangalore for Padukone.

Eventually, Padukone would learn to pull on two track suits — or three — at the same time, and take off on long distance runs in minus-20 degree celsius.

Eventually, Prakash Padukone was ready for the onset of Denmark’s coolest one — Morten Frost.

***

It’s an equation that evolved from shared competitive instinct and a pair of unsatiated ambitions. “Morten and me were similar in many ways though I was 5-6 years older to him. We had that same streak of intense hard work, dedication and that ability to not be satisfied with what we’d achieved. We’d practice 4-5 days together and just once a week with other players. There were other Danish players perhaps more talented than Morten Frost, but he had that hunger so he went further than the rest,” Padukone recalls.

Denmark was coming off an era of their local hero — Svend Pri whose tactical brilliance and dazzling power on court that led to a string of titles, tragically ended when he took his own life. There was the bombast of Indonesian Lien Swie King known for his scorching, abrasive play, and then the complete anti-thesis: Prakash Padukone and slowly mirroring him was Morten Frost, smooth and fluid footwork, and a series of clears (lobs) with the kill-shot of smashes. “Morten wanted to practice a lot, and Prakash helped his game. Frost looked different from Svend Pri and Flemming Delfs, and their style of play, and we knew it was Prakash’s influence,” Fladberg says. Padukone — ‘paarkash,’ they pronounce his name — would play a lot of deceptive clears and his game was branded “safe but at a high pace.”

It was common for Fladberg and fellow doubles players to collect wagers on how many shots in a rally Frost and Padukone would play. “We would sit and count rally shots — 37, 39, 49,” he recalls.

Of even more amusement to the Danes was how Padukone’s Danish manager Finn Jacobsen who put together the whole stay, guided the young Indian along. “We had great fun watching him go about what must’ve been a tough adjustment — coming from India to this strange country. He needed his manager for everything initially, he couldn’t even call for a taxi himself! We’d laugh a lot about it, but of course he was admired here for his game and his calm nature,” the 1983 world champ says.

Jacobsen was that earliest specimen of the 80s — a professional manager, paid for by a sportsman. “Like how the filmstars have now,” he describes. “He would take care of everything, including pick-up and drops to airports, visas, residence, taxes, PR, press and sponsors. I could focus only on my game,” he says, giving a glimpse of what led Padukone to eventually settle into his current role as a board-member of a non-profit that looks after the minutest aspect of a sportsman’s preps. “I couldn’t have played at the highest level had I been running around for my visas and tickets and everything else. In the 80s of Indian sport, all of this was a rarity,” he says. As was the idea of an Indian as a world-beater, consistently challenging the best.

There’s a little hint of mischief to the suggestion that Frost benefitted more from their sparring and eventually beat the Indian at his game. “It was a good rivalry and we learnt a lot from each other,” he says. There’s pride in his voice when Padukone says Morten Frost has said often in the past that he made a big contribution to the Dane’s game. “This exclusive focus on my game ensured that I could remain at the top of the game for a long time, playing semis and finals 8 to 10 years without distraction. It wouldn’t have happened if Denmark hadn’t happened,” he says.

***

How Prakash Padukone happened to Denmark is a more engaging tale, told gleefully by the man himself.

Unlike Asians who labour their way to building up a physique, the Danes had strong shoulders and were athletically blessed before they went about chiselling their games. Very graceful and technically gifted, instinctively attacking, they were starkly different from the Chinese who played the physical game with visible effortfullness. Like his country’s most famous pastry, Sven Pri had a game that was all airy, crispy, multi-layered in the viennoiserie make of a Danish, though his greatness (at its peak in mid-70s) was flaking out by the time Padukone fetched up on the international circuit. Yet, when called upon to strut badminton courts, he rose in stature like a dough rises to a puff.

In 1979, South Kensington’s concert hall Royal Albert morphed itself into a badminton venue hosting the reigning shuttle royalty of that time, 3000 pounds spent on the transformation. Padukone’s straight sets win was no music to Pri’s ears. “I beat him straight 8, 10 or something. He was so pissed off,” the Indian recalls.

The rant was gobbledygook blending into the irrational. “He said I had come from the forests of India and was used to playing outdoors. He just couldn’t digest the fact that he’d lost to an Indian,” Padukone laughs. In the January of 1980 at the Copenhagen Cup, Padukone would once again send another Dane fulminating. Former World Champion Flemming Delfs wasn’t expecting a wiry Indian to offer him much resistance on his home turf. “I wasn’t an established player, so the Danes were shocked. They just couldn’t stomach it,” he remembers.

The next he heard they had opened their doors and invited him home.

Some Danes genuinely believe — and jokingly and immodestly say — that you are unfortunate if you are not born in Denmark. They jokingly stake claim on Deepika Padukone’s success also. “I think his first child was born here. We know she’s famous. It’s not possible that you are born here and don’t rise to greatness,” Fladberg laughs. As the father-daughter duo cut an adorable figure on Indian television in one of their first tv endorsements together, Prakash Padukone says that three decades ago Denmark taught him that getting a lifesize cut-out and a print ad was the height of glamour.