For Chetan Kumar, homecoming had a new meaning when he returned to Bihar in 2010 after college. As he trod on the dusty bylanes of Maner village, some 40 km from Patna, he was struck by an assortment of visuals — a resident spraying cold water in front of his muddy yard, villagers wading through a clean stretch of Ganga on the eve of Ganga snaan, schoolchildren walking by a diesel train, or a group of women offering prayers on Chhat puja. “I knew I would come back again, and again,” says the 31-year-old photographer. After making a 20-minute documentary on child labour and education in the district, he turned his gaze and his camera towards the landscape before him. And when he downloaded the Instagram application on his smartphone, on a rusty internet connection, it “became the only outlet through which I could show the world my pictures”.

He had a lot of stories to tell, of course, and they came alive in fragments, one by one — bolted doors, a cycle laden with stainless steel utensils, boats drifted ashore, eerie silhouettes of trees and people, mostly people. And yet, he wasn’t isolated in his endeavours. “Suddenly I wasn’t restricted to Bihar or even India. The whole world could see where I come from,” he says.

Instagram, that ubiquitous digital platform where multitudes of visual narratives stream in every second from different parts of the world, may seem like a place you could get lost in easily. It is an assault of images, both personal and public, meant for that immediate impact that plays down emotions and goes straight for the easy win: a like. Yet, somewhere in the middle of this traffic, there is the “right audience” and photographers such as Kumar have benefited immensely from being connected. He got his first assignment from Time magazine to cover the Bihar elections after being “discovered” on the app.

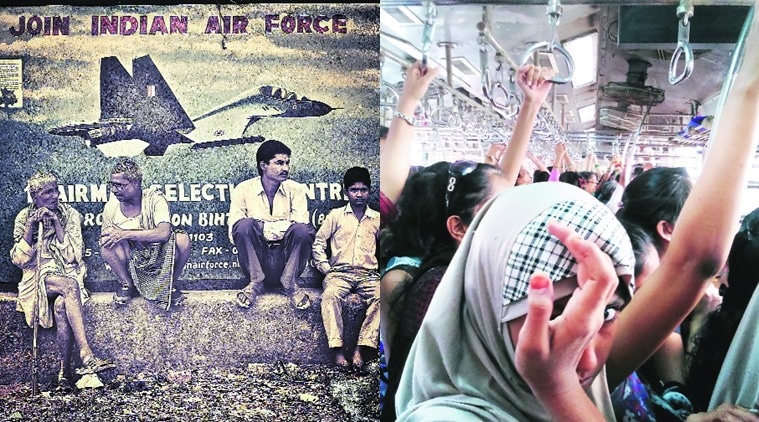

From L to R: An image from Chetan Kumar’s Instagram feed and Anushree Fadnavis’s #traindiaries.

From L to R: An image from Chetan Kumar’s Instagram feed and Anushree Fadnavis’s #traindiaries.

He has held exhibitions in the state and gathered 42,000-odd followers, who he calls his community. “It (my Instagram page) is like daily poetry,” says Kumar, who was also selected to be featured on the Instagram blog.

From photojournalists and photo-bloggers to artists and curators, the platform promotes a lively conversation, often between users who meet through the app for the first time. Anushree Fadnavis, a Mumbai-based photographer who works with a news agency, joined the platform two years ago, “when it was just picking up”. “Now it is exploding. Not only have I ended up meeting people from this country, gotten assignments and commissioned work, I have also gotten in touch with Pakistani photojournalists, among other nationalities,” she says. Mumbai-based filmmaker and photographer Sunhil Sippy, who mostly posts black-and-white images of the streets of Mumbai, discovered a larger community in his city in just a year, one which he could barely tap into in the last 21 years he has lived here. “I didn’t have a sense of people shooting Mumbai. What tends to happen during a shoot is that you’re quite isolated, and it is quite meditative,” says the 44-year-old photographer. “One day, I posted a couple of images, and suddenly, I started to get a sense of connection with all those photographers who were shooting in the city,” he says.

Many users prefer smartphones to high-end cameras, as they are easier to manouevre and allows them to react to their surroundings quickly. Tezpur-based photographer Rahul Singh, 21, whose Instagram page opens up the world of Northeast to the rest of India and has over 34,000 followers, started off with Nokia (Java), and now uses a Yureka. Anurag Banerjee, a 24-year-old photographer based out of Mumbai, uses his iPhone5s to shoot portraits in public spaces, categorising them with the hashtag #loveinbombay. “When you live in a city for so long, you pick up certain nuances to tell a story,” says the freelance photographer. Instagram galleries often evoke a personalised view of the world around them or explores the blink-and-you-miss moments that are otherwise lost in the daily rush.

Sunil Sippy’s black-and-white images of Mumbai.

Sunil Sippy’s black-and-white images of Mumbai.

Fadnavis and her #traindiaries offer an intimate window to a variety of everyday scenes in local trains —scratches on the train walls, found objects, silhouettes and portraits. “Sometimes it is difficult to shoot in a train with a DSLR. There are all these settings and modes to worry about. There are moments where you don’t want to be intrusive. Taking photos from the phone solves that,” says the 27-year-old.

Not all stick to their smartphones though. Sippy uses a Leica and a Hasselblad to shoot images, after which he scans the negatives and processes them, before fitting them into the necessary dimensions and uploading on Instagram. “I don’t use Instagram the way quite a few people use. I just use it as a medium to share and it’s not limited by its own technology,” he says.

Many photographers have learnt to relax their sense of proprietorship over their images. “In the beginning, there was a photographer who wondered if sharing our work on Instagram would reduce their artistic value. You can argue that, but I just don’t take it that seriously. It doesn’t mean that I don’t take my photography seriously. I just don’t take fame seriously,” says Sippy. In return, they get the kind of feedback a physical exhibition would take years to achieve. “Before Facebook and Instagram, photographers could be exclusive with their work. But you don’t feel like you are devaluing your work. In fact, you’re getting a new and bigger audience and not just because somebody knows you. It’s a democratic set-up,” says Kumar.

Tezpur-based Rahul Singh’s feed offers glimpses of the Northeast.

Tezpur-based Rahul Singh’s feed offers glimpses of the Northeast.

In his column for The New York Times, titled ‘Serious Play’, photographer and author Teju Cole puts forth significant queries about Instagram and the way creative artists use it to further their artistic endeavours. “Instagram, like any other wildly successful social-media platform, is by turns creative, tedious, fun and ridiculous. If you follow the wrong people, it can easily become a millstone around your neck. (There can be mild, but real, social costs to following and then unfollowing.) But the activity of individual photographers is an area in which it can be revelatory — not for the stunning individual image but for the new seams of insight it reveals,” he writes.

As more and more photographers subscribe to the format, we wonder if the longevity of a photograph suffers from the transient nature of the internet. “I do see a paradox,” says Kumar, “But this attention is also very important. The way television uses attention, or any other medium like cinema or theatre, in the same manner, photography also has to fight for it.”