On terrorism and Pakistan, hard lessons from the BRICS Summit

New Delhi has no real ability to project military power across its borders.

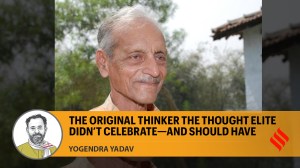

PM Narendra Modi with Presidents Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping in Goa. Both Russia and China see Pakistan as a potential ally in their anti-jihadist game. (Source: AP)

PM Narendra Modi with Presidents Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping in Goa. Both Russia and China see Pakistan as a potential ally in their anti-jihadist game. (Source: AP)

In his closing statement at the just-concluded BRICS Summit in Goa, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that BRICS member-states were “agreed that those who nurture, shelter, support and sponsor such forces of violence and terror are as much a threat to us as the terrorists themselves”.

The BRICS 109-paragraph Summit declaration, however, does not have a single sentence reflecting this purported consensus — not even the words “nurture”, “shelter” or “sponsor”.

Worse, from India’s optic, the Summit declaration calls for action against all United Nations-designated terrorist organisations which include the Lashkar-e-Toiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad, but names only the Islamic State and al-Qaeda’s proxy, Jabhat al-Nusra — both of which are threats to China and Russia, but not to India.

China’s President Xi Jinping said success against terrorism made it imperative to “address both symptoms and root causes” — a stock phrase Islamabad often uses to refer to the conflict over Kashmir. Russian President Vladimir Putin made no mention of terrorism emanating from Pakistan at all.

Add to this the United States’ studied refusal to be drawn into harsh action against Pakistan, and there’s a simple lesson to be drawn: less than a month after it began, India’s campaign to isolate Pakistan is not gaining its desired momentum.

No one seriously disputes New Delhi’s right to punish cross border-terrorism — even Pakistan’s best friend China offered no reproach when India struck across the Line of Control, and has been quietly counselling Pakistan to get its house-jihadists under control.

However, there’s a big difference between quiet counsel and public censure — Pakistan is far too useful to all the world’s big powers in a number of ways.

For one, both China and Russia, as well as Iran, see Pakistan as a potential ally in their anti-jihadist game. The Islamic State and al-Qaeda, now being slowly choked in Syria and Iraq, are likely to divert a significant portion of their resources to Afghanistan as the war against them proceeds. That means numbers of Uighur and Russian Muslim jihadists could be located close to their homelands’ borders. Beijing and Moscow will then need Islamabad’s cooperation.

Interestingly, both countries have already expanded their covert outreach to the Afghan Taliban, seeing them — rightly or wrongly — as a counterweight to the Islamic State.

Then, Moscow is increasingly sceptical about the US combating Islamists. Last year, when Putin travelled to New York, he called for “a genuinely broad international coalition” to fight the Islamic State. His efforts to bring one about on Syria, though, have fallen apart — leaving Moscow persuaded that the United States’ war on terror is insincere and opportunistic.

Finally, New Delhi has no chips to cash in because of its dogged refusal to be embroiled in its allies’ wars. Given New Delhi’s indecision on participation in the war against the Islamic State, it is not in any position to ask Russia for a return favour on Pakistan. Nor can New Delhi credibly ask the US to jettison Pakistan when India remains, at best, a marginal provider of security in Afghanistan.

New Delhi has no real ability to project military power across its borders. Its economic influence is limited, compared to that of China, or even Russia.

By contrast, Pakistan profits from being a nuisance. Its covert services have birthed toxic proxies, who can spawn savage small wars across the region. This doesn’t make Pakistan popular, but it does give it influence.

This is a good time for India to learn some — sometimes painful — lessons, and to take a clear-eyed, unsentimental look at the problems at hand.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05