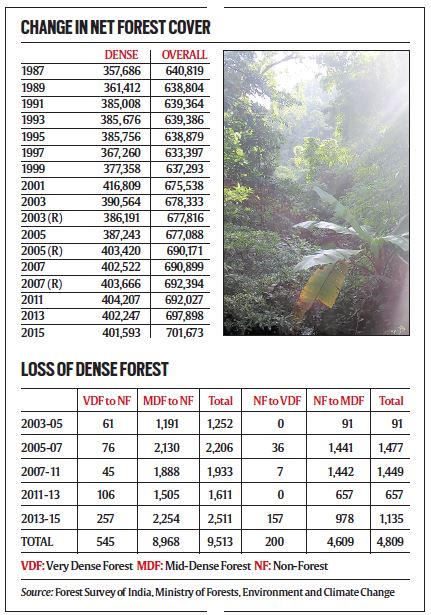

The first time the Forest Survey of India (FSI) measured the country’s forest cover was in 1987, using satellite data captured during 1981-83. Its latest biennial report released recently shows that India has gained 60,854 sq km of forests over the past three decades, 43,907 sq km having been added under the dense forest category.

In the last two years, while the gain in overall forest cover has been an impressive 3,775 sq km, our dense forests have shrunk by only 654 sq km. These figures were highlighted by the government to claim an overall stability in India’s forest cover.

Indeed, this is a remarkable feat considering the intense pressure on forest land for the agricultural, industrial and infrastructural needs of a rapidly growing population. But before celebrating the achievement, there is need to look behind the numbers.

Mid-Dense Forest in Palamu Tiger Reserve, Jharkhand. (Express Photo by: Jay Mazoomdaar)

Mid-Dense Forest in Palamu Tiger Reserve, Jharkhand. (Express Photo by: Jay Mazoomdaar)

The FSI uses satellite images to identify green cover, and does not discriminate between natural forests, plantations, thickets of weeds such as juliflora and lantana, and longstanding commercial crops such as palm, coconut, coffee or even sugarcane. In the 1980s, satellite imagery mapped forests at a 1:1 million scale, missing details of land units smaller than 4 sq km. Now, the refined 1:50,000 scale can scan patches as small as 1 hectare (100 metres x 100 metres), and any unit showing 10 per cent canopy density is considered forest. So millions of these tiny plots that earlier went unnoticed, now contribute to India’s official forest cover.

This can throw up very interesting results. Take Delhi, for example. The first FSI report recorded only 15 sq km of forests in the capital. The latest report found 189 sq km — an over 12-fold increase in three decades. Nearly a third of this is recorded under the ‘dense’ category. So how come oxygen-starved Delhiites do not have a guide map to take a breather in these ‘forests’?

Similarly, the highly agricultural Punjab and Haryana have managed to add more than 1,000 sq km each of forests since the 1980s. Arid Rajasthan has gained as much as 30%. A third of Tamil Nadu’s forests are on private land that also has a fifth of the state’s dense forests.

Similarly, the highly agricultural Punjab and Haryana have managed to add more than 1,000 sq km each of forests since the 1980s. Arid Rajasthan has gained as much as 30%. A third of Tamil Nadu’s forests are on private land that also has a fifth of the state’s dense forests.

Even as invasive weeds and commercial plantations masqueraded as ‘forests’ across the country, India kept losing its vital dense forest cover (canopy density of 40% or above). For example, dense forests have shrunk by 2,254 sq km in Gujarat, and by 1,887 sq km in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana since the first FSI report.

Story continues below this ad

What’s worse, the net loss, or gain, in dense forests does not show how much is actually being lost. A dense forest can deteriorate to open forest (10%-40% canopy density), or can be wiped out altogether to become non-forest. On the other hand, open forests can improve in density, and even non-forests can grow into open and, subsequently, dense forests over a length of time.

Since 2003 (see chart), 9,513 sq km of India’s dense forests have been wiped out, and have become non-forest areas. What offsets this loss in the forest reports is the conversion of non-forest areas to dense forest every two years. Since 2003, a total of 4,809 sq km of non-forest have become dense forest. In the last two years alone, this has added 1,135 sq km under the best forest category. The secret: these are all fast-growing plantations — not detected by satellites in the early stages, but considered dense forests when they ultimately show up.

Planting mixed native species is perhaps the best means to create new forests. But they cannot compensate, certainly not overnight, for the loss of old-growth natural forests. For three decades, our net dense forest cover has remained stable on paper. There is nothing in the FSI reports until 2005 to show how much of these prime forests were actually lost, and compensated for, by plantations. But the data in the last 10 years reveal that we are destroying around 1,000 sq km of dense forest every year, and compensating for nearly half of this with plantations.

Depending on where one stands, one can be smug that we are losing only this much and not more, or worry that so much is being lost. Either way, this realisation — and not the jugglery of marginal net gains or losses — is the real takeaway from our forest reports.

Open Forest in Ramnagar Forest Division, Uttarakhand. (Express Photo by: Jay Mazoomdaar)

Open Forest in Ramnagar Forest Division, Uttarakhand. (Express Photo by: Jay Mazoomdaar)

Mid-Dense Forest in Palamu Tiger Reserve, Jharkhand. (Express Photo by: Jay Mazoomdaar)

Mid-Dense Forest in Palamu Tiger Reserve, Jharkhand. (Express Photo by: Jay Mazoomdaar) Similarly, the highly agricultural Punjab and Haryana have managed to add more than 1,000 sq km each of forests since the 1980s. Arid Rajasthan has gained as much as 30%. A third of

Similarly, the highly agricultural Punjab and Haryana have managed to add more than 1,000 sq km each of forests since the 1980s. Arid Rajasthan has gained as much as 30%. A third of