© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

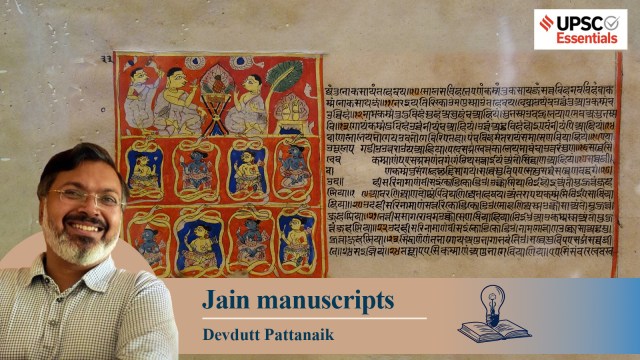

The Nature of Karma, from an Uttaradhyayana Sutra manuscript, Cambay, Gujarat, about 1460 AD. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Nature of Karma, from an Uttaradhyayana Sutra manuscript, Cambay, Gujarat, about 1460 AD. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)In Jain thought, every action creates a transaction in the cosmic account. Consumption incurs debt. Fasting reduces debt. Charity generates credit. Liberation is achieved when there is no debit or credit left. Those who teach this path are the Tirthankaras, the spiritual fordsmen who help others cross the river of existence.

The Jain community itself is organised into four categories: the layman, the laywoman, the monk, and the nun. Monks and nuns renounce worldly life and discipline their bodies to free the soul, while lay followers provide for the needs of the monastic order, and transmit Jain teachings by building Jain temples and funding the creation of manuscripts.

In ancient times, temples were repositories of stories and symbols. Their walls and pillars carried images of Tirthankaras, inscriptions of Jain cosmology, and episodes from the lives of enlightened beings. Although manuscript creation began in 500 AD, it was not yet a major activity.

Many artworks were created on cloth, showing sacred symbols or pilgrim maps. Those who could not travel to sacred sites would worship these maps. Those who could not afford to build temples, would paint stories of the sages on cloth. There were stories like that of a Jain muni who remained calm when a hunter, frustrated at being unable to hunt any creature, sent his dogs to attack him.

When Islamic rule spread across India after 1200 AD, temple building became difficult. Many shrines were destroyed or repurposed. The Jain community shifted its energy to the written word, transforming the art of manuscript making into a central cultural expression. What had once been a minor practice became a major industry.

Though manuscripts were produced, literacy was poor in the community who preferred ritual practice revolving around the temple. Manuscript production was not about reading but about earning spiritual credits.

This shift gave rise to a vast ecosystem of artisans — paper makers, painters, calligraphers, carpenters, and metal workers. A scribe wrote with styluses designed by specialised craftsmen. Libraries called ‘bhandars’ were built to preserve the manuscripts, often inside temple complexes.

In the north, early manuscripts were inscribed on birch bark, while in the south, palm leaves were used. With the arrival of paper from Central Asia around the thirteenth century, introduced through Mongol networks, Jain scribes began using this new medium extensively. The paper was smooth, portable, and easier to paint upon, allowing for refined visual detail.

The manuscripts were placed in boxes and the boxes in libraries. When in use, they would be removed from boxes and wrapped in cloth. The major centres of patronage were Konkan, Gujarat, and Rajasthan – prosperous regions of the western coast that supported rich merchant guilds and monasteries.

The Jain manuscript became famous for its meticulous structure. Each page followed a precise layout — sometimes divided into one, three, or five panels — and measurements were guided using a template that produced a grid of dots on the paper. These dots ensured that text lines remained parallel and that the illustrations were symmetrically placed. Neatness, order, and discipline – values central to Jain philosophy – thus found artistic expression in the geometry of the page.

Colour was equally significant. The preferred palette included red derived from cinnabar, ochre, gold leaf for divine glow, and, above all, blue from lapis lazuli, a rare and costly pigment imported from Afghanistan. The deep blue became the signature tone of Jain miniature painting, symbolising serenity and infinity.

Figures were stylised: faces were often in profile, yet both eyes were shown, creating a distinct visual rhythm that separated Jain art from other Indian styles.

The subjects of the manuscripts were drawn from the Kalpa Sutra and other sacred texts. The Kalpa Sutra narrated the lives of the Tirthankaras, explaining the cycles of time, the geography of the Jain cosmos, and the unending flow of creation and dissolution. It also listed the cosmic heroes — the nine Vasudevs, their Baladev brothers, and the Prativasudevs who opposed them — alongside the twelve universal monarchs or Chakravartins and the twenty-four Tirthankaras.

Each Tirthankara’s life was mapped through the five sacred events, known as the Pancha-kalyanak: conception, birth, renunciation, enlightenment, and liberation. The manuscripts often repeated these stories, reflecting the timeless rhythm of Jain teaching rather than individual innovation.

Many also included appendices such as the Kalaka Acharya Katha, recounting how the sage Kalaka invited foreign kings to punish an arrogant ruler of Ujjain who had abducted his sister. Another popular story was on the rebirths of King Yasodhara and his mother – who discovered the adulterous behaviour of Yasodhara’s wife.

In the 19th century, as part of reform movements, many scholars wanted to preserve and translate old Jain manuscripts. This was resisted by the orthodox people. However, when the translations were done finally, it was clear to scholars like Herman Jacobi that Jainism was a separate religion not a Hindu sect. Jain as a category emerged only in the 1881 British census and was promoted to oppose Hindu reform movements like Arya Samaj that sought to deny Jains their separate identity.

The Jain manuscript became both scripture and art object — a sacred ledger recording humanity’s debits and credits before eternity. Through calligraphy, geometry, and disciplined colour, the Jain mind expressed its vision of order in a universe governed not by chaos or emotion but by the quiet logic of karma.

What is the concept of karma in Jain philosophy? How did Jain minds express their vision of order in a universe governed not by chaos or emotion but by the quiet logic of karma?

When and why did the Jain community shift its energy to the written word, and how did this transform the art of manuscript making into a central cultural expression?

The Jain community itself is organised into four categories: the layman, the laywoman, the monk, and the nun. How do they work together to sustain both the spiritual discipline and the preservation of Jain teachings?

The Jain manuscript became both scripture and art object — a sacred ledger recording humanity’s debits and credits before eternity. Explain.

(Devdutt Pattanaik is a renowned mythologist who writes on art, culture and heritage.)

Share your thoughts and ideas on UPSC Special articles with ashiya.parveen@indianexpress.com.

Click Here to read the UPSC Essentials magazine for November 2025. Subscribe to our UPSC newsletter and stay updated with the news cues from the past week.

Stay updated with the latest UPSC articles by joining our Telegram channel – IndianExpress UPSC Hub, and follow us on Instagram and X.

Read UPSC Magazine