What the FIFA World Cup draw does not reveal at first glance

FIFA World Cup 2026: Most teams will have to deal with drastic changes in weather and altitude while some will have to travel nearly 5,000 kilometres during the tournament co-hosted by USA, Canada and Mexico

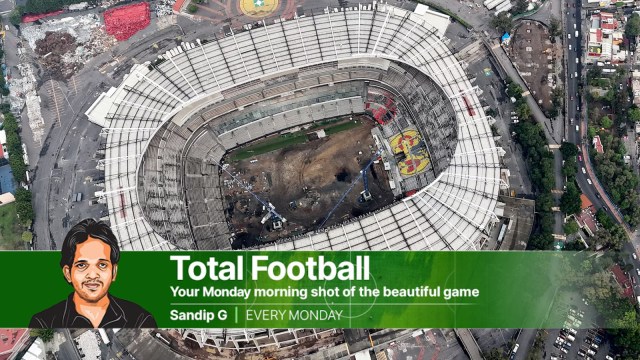

FIFA World Cup 2026: An aerial view of the renovation work at the iconic Azteca Stadium in Mexico City, perched 2,200m above sea level. (Reuters)

FIFA World Cup 2026: An aerial view of the renovation work at the iconic Azteca Stadium in Mexico City, perched 2,200m above sea level. (Reuters)The World Cup draw brought certainty; teams have learned about the adversaries, dates and venues. But now begins the hard part: the preparation bit, the last and hurried lap of assembling a group capable of winning the tournament. And then, the layered intricacies of the draw unravel, often ensuring that the fixtures do not mean what they seem to mean at first reading. A favourable group does not always mean so, and does not often unfold favourably.

For instance, Spain coach Luis de la Fuente was reasonably delighted when his fleet of European Champions’ group-stage rivals was revealed. Saudi Arabia (ranked 60), freshers Cape Verde (68), and Uruguay (16), the only stiff opponents. He was all smiles and chuckles during the ceremony, whenever the cameras zoomed in on him. He would smile less when he charts the travel plans. Two games are in Atlanta, in America’s Southeast, the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. The temperature should be on the higher side (33 to 35 degree Celsius), spells of rain are frequent, but the retractable roof would ensure friendly climes.

But after the week-long stay in Atlanta, Spain head to Guadalajara, 2,800 kilometre apart, at an altitude of 1700m above sea level, in a different time zone, with thinner air and a typical subtropical climate. The geographical vastness is a strong reason Fuente — on second reading of the fixtures — stresses that his team is not the group favourites. “What worries me most is the amount of travel or the long distances between matches. What concerns us most is having to travel so many kilometres every three or four days,” he told Spanish sports paper Diario AS.

From wrapping up the Saudi Arabia game to striding out into the imposing Estadio Guadalajara, Spain have a turnaround time of only three days if the travel time is considered. Disadvantaging them deeper is that they are countering a strong side, managed by Marcel Bielsa, in conditions they are more accustomed to than the Spaniards. Playing in the late evening might help Spain escape the sweltering heat of the afternoon, but it’s when the air gets thinner. Rains and storms could hit. Worse, the team that loses — or ends up second in a hypothetical situation that they are either Spain or Uruguay — would end up travelling to Miami for the round of 32 encounter against holders Argentina.

Distinct venues

The team that lifts the World Cup would also be the one that cracks the geographic immensity of the vast continent. The teams scheduled to play games in Mexico, the host nation aside, would already be cussing the misfortune. Agonisingly, South Korea would play all their games in Mexico, all three of its venues with distinct characters too.

The most imposing could be the iconic Azteca in Mexico City, the stadium of Diego Maradona’s Hand of Goal. Visitors gasp for breath, perched as it is 2,200 metres above sea level. Before renovation, Mexico used to schedule all their important home games to suffocate its opponents. In five decades, Mexico have lost only a pair of World Cup qualifying games here. The thinner air sometimes makes the ball move wickedly. The American goalkeeper Tim Howard once likened it to “playing saucer”. “It’s the most difficult place in the world to judge a shot for a goalkeeper.” The home crowd’s hostility intensifies the atmosphere, where the visiting side often feels like convicts on death row. “A dislocating place,” Bruce Arena, a former USMNT coach, once said.

US President Donald Trump and FIFA President Gianni Infantino during the 2026 FIFA World Cup draw at the Kennedy Center last Friday. (AP Photo)

US President Donald Trump and FIFA President Gianni Infantino during the 2026 FIFA World Cup draw at the Kennedy Center last Friday. (AP Photo)

It’s where South Africa and Mexico flag off the tournament on June 11, and one of Czechia/Denmark/North Macedonia/Republic of Ireland encounters Mexico. The third Mexican venue, Monterrey, is not at dizzying heights. But the city in Northeastern Mexico, closer to the US border and only 450m above sea level, is the hottest and stuffiest venue in the tournament, with barely any rain and an average temperature of 33 degrees Celsius and often nudging 40 degrees. Heatwaves are frequent, too. A peep of the majestic Sierra Madre Orienta mountain in the background is perhaps the only relief for the eyes. A World Cup in Mexico (1970) prompted one of the biggest rule changes in football, the use of substitutes.

The most pleasant would be the venues in Canada—Vancouver and Toronto. Both are cities in the low-altitude zone, and are immune to extremes of heat or rain. America’s cities are trickier; four of the eleven venues have a retractable roof, and hence the temperature could be regulated. For other venues, conditions could vary depending on the time of the match. Afternoon fixtures — catering to Europe’s audience — would be the unkindest of all. Both Miami and New Jersey could be stuffy, with their combination of heat and humidity. San Francisco, on the West Coast, would be hot but without the merciless humidity of the East. If the Club World Cup last June were a precursor, managers and players would be fretting over heat. England coach Thomas Tuchel is already planning to keep his substitutes indoors to not drain them. England, placed in a tough group that also features Ghana and Croatia, play in Dallas, supposedly the most pleasant venue in the US, Boston and New York. If the draw was unkind, the venues were less so. But for all the paranoia, the two World Cups in Mexico (1970 and 1986) and the one in the USA (1994) were high-quality events.

In the weather-venue draw, some teams are luckier than others. Cape Verde would end up travelling 4,700 kilometres, Uruguay 4,500 and Scotland 4,200. Erling Haaland-powered Norway is perhaps the luckiest, playing two games in Boston and one in New York, which is only a 350km trip one way. France, similarly, play their games in the Philadelphia-New York-Boston circuit. The fixtures, thus, do not mean what they seem to mean at first reading.