The protest against the glorification of Gandhi in Ghana is hardly the first time that Satyagraha leader has been called out for his racist beliefs. In 2015 a protest had broken out against Gandhi in Johannesburg. In 2014 an agitation at Irving, Texas targeted the installation of a life-size statue of Gandhi. Protests against Gandhi’s image have also taken place in San Francisco and London in the past.

What is the evidence being cited against Gandhi?

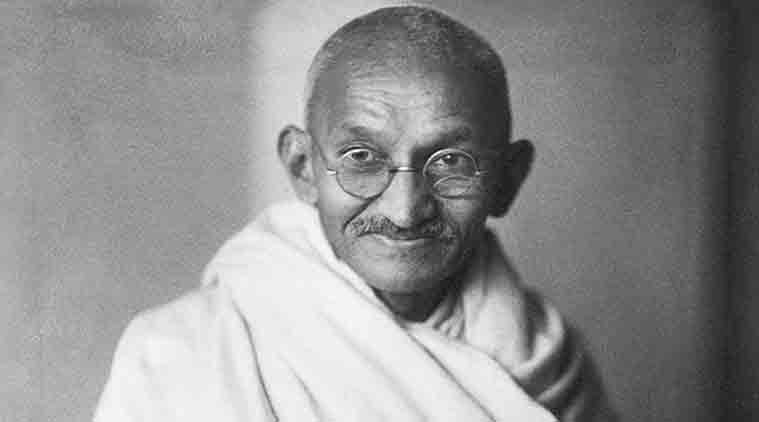

Gandhi landed in South Africa in 1893 and the two decades he spent among the Indian diaspora there played an instrumental role in shaping both his personality and his ideas of satyagraha or non-violent resistance. Yet it his writing during these years that are often cited by his critiques as demonstrating a racist ideologies.

For instance, in 1894, he is believed to have written that “a general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa. Even the children are taught to believe in that manner, with the result that the Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.” The term Kaffir is used in a derogatory sense in South Africa to refer to blacks.

Gandhi’s discomfort in Indians being treated the same way as black South Africans was evident yet again in September 1896 when he wrote, “Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

Gandhi landed in South Africa in 1893 and the two decades he spent among the Indian diaspora there played an instrumental role in shaping both his personality and his ideas of satyagraha or non violent resistance. (Wikimedia Commons)

Gandhi landed in South Africa in 1893 and the two decades he spent among the Indian diaspora there played an instrumental role in shaping both his personality and his ideas of satyagraha or non violent resistance. (Wikimedia Commons)

In his struggle seeking justice and equality for Indians in South Africa, he was put behind the bars on several occasions. In his book, ‘Gandhi: The Man, His People, and the Empire’, Gandhi’s biographer and grandson Rajmohan Gandhi writes that on one such occasion, Gandhi had written about his experience of sharing the cell with black people. “Many of the native prisoners are only one degree removed from the animal and often created rows and fought among themselves,” he wrote. However, Rajmohan Gandhi also goes on to write that by the time he left South Africa he did gain a greater understanding of African people and often recollected his interactions with leaders there.

How has Gandhi’s ‘racist attitude’ been represented in history?

Few would perhaps disagree with the fact that Gandhi’s image throughout the world is largely associated with peace and truth. Several African leaders have themselves held up the role that Gandhi has played in mobilising the African movement against the British. Nelson Mandela, for instance, is known to have been hugely inspired by Gandhi and his methodologies. “It was here that he taught that the destiny of the Indian community was inseparable from that of the oppressed African majority. That is why, amongst other things, Mahatma Gandhi risked his life by organising for the treatment of Chief Bhambatha’s injured warriors in 1906,” he said in 1998.

Story continues below this ad

[ie_backquote quote=”After all, Gandhi too was an imperfect human being” cite=”Rajmohan Gandhi” large=”true”]

Yet in recent times some historians have disagreed with the image of Gandhi as a mobiliser of African resistance. In 2015, South African academics Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed came out with a book that raked up quite a controversy. In ‘The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire’, they write about how Gandhi’s kept out Africans from the struggle for equality that he carved out for Indians there. At the same time, his attitude towards Africans was almost mirroring that of the British.

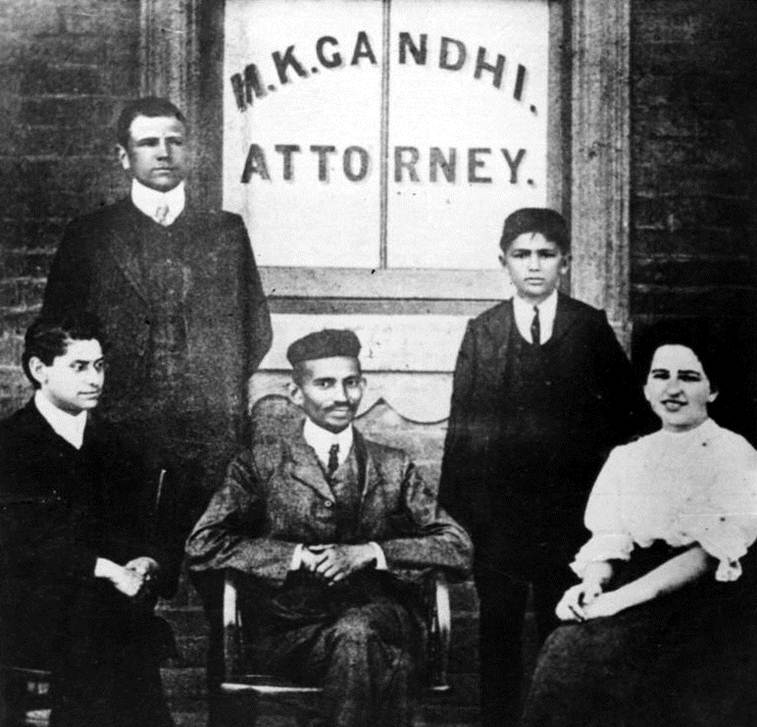

They also write about Gandhi’s role in the Boer war that was fought between the British and the local Boer group, wherein he provided all the support to the former. “Gandhi marshalled a group of mostly South African-born Indian stretcher-bearers and marched into the war zone to support fallen British troops. Gandhi saw the war as an opportunity to demonstrate his loyalty to Empire,” they write. They further note that in doing so Gandhi was hoping to give impetus to his pleas for an equal status for Indians.

Gandhi in the Boer war (Wikimedia Commons)

Gandhi in the Boer war (Wikimedia Commons)

Historian Ramachandra Guha, who has written two extensive biographies of Gandhi, has dealt extensively with his years in South Africa. In his book, ‘Gandhi before India’, Guha notes that Gandhi should be recognised as being among Apartheid’s first opponents since he was the one to have led the first protest against racial laws in South Africa. In the second and more recent volume of Gandhi’s biography, Guha notes that “the two decades that Gandhi spent in the diaspora were crucial to his intellectual and moral development”. “It was here that he first thought of and applied the technique of non-violent resistance known as satyagraha.”

Story continues below this ad

Responding to those who oppose Gandhi including several notable Indian ideologues, Guha writes that “their writings are vital to a fuller understanding of Gandhi’s thought and practice”. “What Gandhi said and did makes sense only when we know what he was responding to,” he adds.

In his response to the allegations made by Desai and Vahed, Rajmohan Gandhi had written in a column that indeed Gandhi during his youth did support the imperial cause and was on several occasions prejudiced and ignorant about South African blacks. However, he insists on analysing Gandhi as a human being. “After all, Gandhi too was an imperfect human being. However, on racial equality, he was greatly in advance of most if not all of his compatriots; and the struggle for Indian rights in South Africa paved the way for the struggle for black rights,” he writes.

Citing passages written by Gandhi to refer to Indians as ‘infinitely superior’ to Africans, the petitioners protested against glorifying Gandhi despite the racist attitude he is believed to have held during his stay in South Africa. (Archives)

Citing passages written by Gandhi to refer to Indians as ‘infinitely superior’ to Africans, the petitioners protested against glorifying Gandhi despite the racist attitude he is believed to have held during his stay in South Africa. (Archives)

Gandhi landed in South Africa in 1893 and the two decades he spent among the Indian diaspora there played an instrumental role in shaping both his personality and his ideas of satyagraha or non violent resistance. (Wikimedia Commons)

Gandhi landed in South Africa in 1893 and the two decades he spent among the Indian diaspora there played an instrumental role in shaping both his personality and his ideas of satyagraha or non violent resistance. (Wikimedia Commons) Gandhi in the Boer war (Wikimedia Commons)

Gandhi in the Boer war (Wikimedia Commons)