The day was February 14, 1850. Major General Sir Henry Marion Durand, then serving as a political agent in Bhopal, welcomed a baby boy. The child, Henry Mortimer Durand, would later be remembered for several reasons, but primarily for his role in negotiating the 1893 boundary between British India and Afghanistan — the Durand Line — which would go down in history as one of South Asia’s most unstable borders.

More than a century later, the line still bleeds. Last week, Afghanistan and Pakistan reignited conflict along this frontier. Afghan authorities accused Pakistan of carrying out airstrikes on Kabul. On October 12, the Taliban launched a counterattack on Pakistan’s Frontier Corps positions along the Durand Line. The Taliban government’s Defense Ministry stated, “If the opposing side again violates Afghanistan’s territorial integrity, our armed forces are fully prepared to defend the nation’s borders and will deliver a strong response”.

The renewed clashes have revived the question: What exactly is the Durand Line? And why does it remain one of South Asia’s most complicated border conflicts?

Story continues below this ad

The Durand Line

The Durand Line is a 2,640-kilometer (1,640-mile) border dividing modern Afghanistan and Pakistan. While the exact location of the line is debated, the West and the United States recognise it as the official border between modern Afghanistan and Pakistan. The landscape of the area (present-day southeastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan) is mostly composed of arid and semi-arid highlands. “The mountains which at times attain a height of 7000 ft have in places basins and valleys where some settlements are to be found. Hardly any roads have been built here,” notes former diplomat Satinder Kumar Lambah in his 2011 policy paper The Durand Line, published by the Aspen Institute India.

This area, Lambah writes, includes the seven tribal agencies of the current Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA): Khyber, Bajaur, Mohmand, Orakzai, Kurram, North Waziristan, and South Waziristan. Also part of FATA are the six frontier regions and the districts of Bannu, Kohat, and Dera Ismail Khan.

The Durand Line was established during the tenure of Mortimer Durand, who served as the Foreign Secretary of the Government of India from 1884 to 1894. His time in office coincided with the peak of the rivalry between British India and Russia, also known as the Great Game, over imperial expansion into Central Asia.

Story continues below this ad

Abdur Rahman Khan, the grandson of Dost Mohammed, who was a Russian pensioner in Samarkand, in current-day Uzbekistan, crossed into Afghanistan in January 1880 as a claimant to the throne. His predecessor, Yakub Ali, son of Sher Ali (Emir of Afghanistan from 1863 to 1866 and again from 1868 to 1879), had fled after hearing news of the declaration of the Second Afghan War in 1878. Ali ruled briefly, from February 21 to October 1879, ultimately making his tenure an interim one, paving the way for Abdur Rehman’s return.

“On taking over as Amir with British assistance in July 1880 he was insistent on not having a British Resident in Kabul, while accepting the other conditions of the Treaty of Gundamak (1879),” writes Lambah. By this treaty, control of the Khyber Pass and the border districts of Kurram, Pishin, and Sibi was seized from the Afghans. However, Lambah points out that “to sweeten the blow, an annual subsidy of Rs 6,00,000 (then £ 60,000) was granted, which was to be later doubled in 1893 to sweeten another blow that was to be imposed by the Durand Agreement.”

By 1888, Abdur Rahman had managed to reclaim Kandhar and Herat with their surrounding areas. These regions had earlier been severed from Kabul as a part of Lord Lyotton’s plan to carve them into separate states to make it difficult for the Russians or any other potential aggressor to occupy Afghanistan. Alongside, he had to crush two major rebellions and kill hundreds of political opponents.

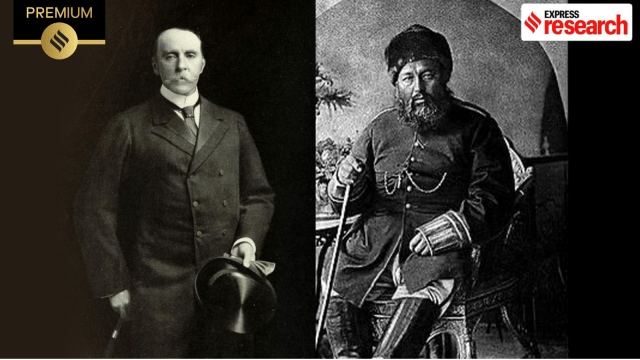

Abdur Rahman Khan in Rawalpindi, with the British viceroy of India, 1885 (Tarikh-i-Pakhtunkhwa)

Abdur Rahman Khan in Rawalpindi, with the British viceroy of India, 1885 (Tarikh-i-Pakhtunkhwa)

Meanwhile, the Panjdeh Crisis occurred in 1885, during which Russian forces attacked the Afghan town of Panjdeh near the disputed northern Afghan boundary. Although diplomatic efforts prevented the situation from escalating into war, the border between Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier of British India remained a persistent point of contention.

Story continues below this ad

In 1893, Abdur Rahman finally proposed to the Marquess of Lansdowne, Viceroy of India, that a conference be held in Kabul to agree on a formal delineation of the Afghan-India border. At this point, “Durand was sent to Kabul to attend this conference and negotiate with Abdur Rahman, considered ‘a catankerous and suspicious old savage’ by Landsdowne,” notes Harold E Raugh Jr, retired senior US Army officer, in Afghanistan at War: From the 18th-century Durrani Dynasty to the 21st Century (2017).

An agreement was reached quickly, perhaps facilitated by Durand offering to increase the Emir’s annual subsidy by £300,000. On November 12, 1893, the Emir signed and sealed a treaty renouncing all claims to the territory extending from the Hindu Kush to the westernmost limits of Baluchistan. This large area contained the formerly contested lands of Bajaur, Dir, Swat, Buner, Tirah, the Kurram Valley, and Waziristan. As a result, the frontier tribesmen acquired a legal status, becoming ‘British protected persons.’

According to Lambah, the area in respect of which negotiations between the Amir and Mortimer Durand took place has long been inhabited by the Pakhtuns. “The ancient Greek historian, Herodotus,” he writes, “referred to the land they occupied (between the Oxus and Indus rivers) as Pakhtia… It has appeared in numerous writings, including those during the reign of Emperor Shahabuddin Ghauri, and more recently in poems composed by Akhund Darwazeh (d.1838) and Ahmad Shah Abdali.”

In an email interview, Vinay Kaura, Associate Professor at Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Rajasthan, states: “The Durand Line was a cartographic outcome of British India’s desire to create a buffer zone on its northwest frontier against perceived Russian threat and to demarcate the sphere of influence with the Afghan ruler, Amir Abdur Rahman”. However, this frontier is among the various other issues, such as the Pashtunistan issue, anti-Pakistan forces in Afghanistan, etc, that have caused the straining of relations between the two nations.

Story continues below this ad

The Pashtuns

The legality of the Durand Line, as cited by academic David Harms Holt in Afghanistan At War (2017), lies in Article 5 of the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1919, which formally accepted the Durand Line as the boundary between Afghanistan and British-ruled India. The line has since then been criticised as illogical because it splits a nation in two and divides a tribal community.

The community affected is that of Pashtuns, who live on either side of the border and who led a movement for an independent state of Pashtunistan in the mid-20th century. According to Kaura, “The Durand Line has split the Pashtun heartlands, undermining kinship, mobility, and trade connections. With divided loyalties and new governing structures, identity politics has also become more complicated. Cross-border tribal grievances and cultural dislocation have aggravated insurgencies”.

Sher Ali Khan (center) and his delegation in 1869 (Wikipedia)

Sher Ali Khan (center) and his delegation in 1869 (Wikipedia)

Tribes on both sides of the frontier inter-marry, engage in trade, and share traditions and rituals. While there have never been accurate population statistics of the Pashtun areas, Lambah cites a 2010 research paper, The Durand Line, from the House of Commons Library in his work, which mentions that “there are at least 35 million Pashtuns living in the two countries. Pashtuns have been said to comprise an estimated 42% of the population of Afghanistan, which, at around 11.8 million, makes them the largest single ethnic group in the country. In Pakistan, Pashtuns have been said to comprise an esti- mated 15% of the population, which, at around 26.2 million, makes them the second largest ethnic group in the country”.

On the uniqueness of the Durand Line, Kaura says: “Unlike other South Asian boundaries, this border was a unique colonial era demarcation that bisected Pashtun and Baloch lands, while disregarding tribal coherence. The Agreement, while creating a buffer zone between British and Russian interests, directly carved up existing socio-political landscapes.”

Story continues below this ad

The foundation of Pakistan

After the foundation of Pakistan in 1947, Afghanistan demanded that the Pashtuns living in the newly formed Pakistan be given the right to choose if they wanted to be part of Afghanistan. This, according to Holt, “would have functionally shifted the border into modern Pakistan. The request was refused by the United Kingdom and Pakistan.” Afghanistan began to disregard the Durand Line and claim Pashtun-occupied territory between the Durand Line and the Indus River, resulting in instability between the two nations in the 1950s and 1960s.

Further, in the 1950s, the United States and Pakistan entered into an arms deal, weakening Afghanistan’s position. Afghanistan also approached the United States, but the latter insisted that it improve its relations with Pakistan and join the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), founded to contain the Soviet Union. Afghanistan, instead, turned to the Soviet Union for arms in 1953. “The result was an Afghanistan supported by the USSR and Pakistan supported by the United States,” writes Holt.

Modern tensions still exist between Pashtuns who either want a Pashtunistan or want to reclaim lands lost to Pakistan by their ancestors, who agreed to the Durand Line. More significantly, the current government of Afghanistan does not officially recognise the Durand Line as the international border with Pakistan. Kaura says, “Unresolved issues between Islamabad and Kabul have been worsened by broader regional instability, militant movements (also claims of militant sanctuaries), and international interventions. Because of the contested nature of the border, economic, diplomatic, and security cooperation remains thwarted, entrenching cycles of mistrust.”

Story continues below this ad

Fencing the Durand Line

Beginning in March 2017, Pakistan started constructing the frontier fence to prevent, as it stated, terrorism, smuggling, and illegal immigration. According to reports, 98% of the fencing was completed by April 2023.

Borki, a village at the border (Wikipedia)

Borki, a village at the border (Wikipedia)

This move, Kaura says, is aimed at curbing cross-border insurgency, controlling irregular migration flows, and consolidating state authority. “It clearly shows Pakistan’s intent to make the border more permanent. But this assertion by Islamabad is regarded by the Afghan state and local Pashtun populations as unnecessary and provocative. This leads to periodic escalation of diplomatic and political tensions.” The fence, like many others across South Asian borders, has disrupted daily life, livelihood, and family/community ties of border communities.

India, the neighbour

On the legitimacy of the Durand Line, India has not taken a clear stance. “This ambiguity,” Kaura notes, “is a reflection of India’s cautious and calculated diplomatic posture. New Delhi has prioritised stable engagement with successive regimes/governments in Afghanistan, vigilantly monitoring Pakistan’s territorial assertions. Since India’s strategic interests in Afghanistan revolve around security, regional connectivity, and counter-terrorism, any instability along the Durand Line has direct implications for these priorities. This makes India’s policy one of pragmatic engagement as well as support for Afghan sovereignty, particularly in instances where Pakistan’s actions are seen as undermining regional equilibrium. This explains India’s consistent support for an Afghan-led, Afghan-owned and Afghan-controlled peace process.”

A negotiated settlement, however, appears unlikely in the near future, says Kaura, citing entrenched political, cultural, and strategic interests. “Regardless of the government/regime in Kabul, Afghanistan’s popular rejection of the Durand Line persists, which is made worse by Pakistan’s unrelenting efforts to entrench the status quo. Regional instability, shifting geopolitical alliances, and the complexity of tribal politics further undermine diplomatic efforts…”

Story continues below this ad

As per Lambah, the transformation of the British description of the Durand Line — from ‘frontier line’ (1893-96), to ‘frontier’ (1919-21), and eventually to ‘International frontier’ (1950) — and Pakistan’s sudden claim after its creation, first describing it as an ‘International border’ (1947) and later leaving it vague, shows a definite lack of consistency.

Kaura argues that while most South Asian borders emerged from the process of decolonisation, “the Durand Line remains exceptional for its enduring lack of consensus between the parties involved because its primary intent was to divide tribes, not states”.

Abdur Rahman Khan in Rawalpindi, with the British viceroy of India, 1885 (Tarikh-i-Pakhtunkhwa)

Abdur Rahman Khan in Rawalpindi, with the British viceroy of India, 1885 (Tarikh-i-Pakhtunkhwa) Sher Ali Khan (center) and his delegation in 1869 (Wikipedia)

Sher Ali Khan (center) and his delegation in 1869 (Wikipedia) Borki, a village at the border (Wikipedia)

Borki, a village at the border (Wikipedia)