Calling it the “project of the century,” Beijing has announced the construction of the world’s biggest hydropower dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibetan territory. The project was introduced in 2020 as part of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan. According to reports, it is to consist of five cascade hydropower stations, producing an estimated 300 million megawatt hours of electricity annually at a cost of approximately 1.2 trillion yuan (US$ 167 billion).

The dam has drawn criticism from the lower riparian states of India and Bangladesh as well as Tibetan groups and environmentalists. Let’s take a look at the river, its hydropower potential, and its future amid climate change.

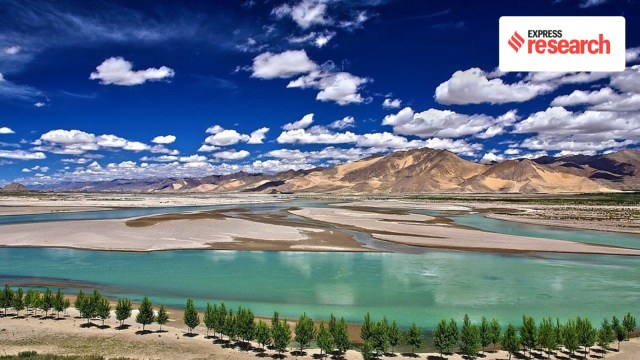

The many names of Yarlung Tsangpo

The Yarlung Tsangpo is the largest river on the Tibetan plateau, originating from a glacier near Mount Kailash. ‘Tsangpo’ means river in Tibetan. According to academic Costanza Rampini in the Political Economy of Hydropower in Southwest China and Beyond (2021), the basin spreads over more than 500,000 sq km of land in China, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh, “though 80% of it lies in China and India.” It runs 2,057 km in Tibet before flowing into India. One fascinating feature of the river is the sharp ‘U’ turn that it takes, known as the Great Bend, at the proximity of Mount Namcha Barwa near the Indian border.

In India, the Yarlung Tsangpo enters Arunachal Pradesh as Siang. The Siang then gathers more streams and flows down towards Assam where it is joined by the Lohit and Dibang rivers. Further downstream, it is known as the Brahmaputra, which in turn flows through Assam before entering Bangladesh.

“Upon entering that country it undergoes one more change in nomenclature, this time accompanied by a sex change – the ‘male’ Brahmaputra, for some reason, becomes the ‘female’ Jamuna,” remarks author Samrat Choudhury in The Braided River: A Journey Along The Brahmaputra (2021). The Brahmaputra, as Jamuna, makes its way towards an eventual confluence with the Ganga, known in Bangladesh as Padma. “This great river of many great rivers finally flows into the Bay of Bengal, after undergoing yet another change of name as the Meghna,” notes Choudhury.

“Like the Nile in Egypt,” says Tibetologist Claude Arpi in Water: Culture, Politics and Management (2009), “the Yarlung Tsangpo has fed the Tibetan civilisation that flourished along its valleys, particularly in Central Tibet.” Approximately 130 million people live within the Yarlung Tsangpo river basin, many of whom are the rural poor. Rampini adds, “Indeed, in North-east India, the YTB [Yarlung-Tsangpo-Brahmaputra] is often referred to as the ‘lifeline’ of the region.”

Hydropower ambitions along YTB

As the YTB descends from the Himalayan mountains to the plains of Assam, it crosses steep slopes and gathers strong energy, which gets scattered in the form of intense summer floods, especially in India and Bangladesh. “The energy that the YTB gains throughout its course also puts the river at the centre of China’s and India’s recent renewable energy development strategies,” says Rampini. For long, both countries have been mobilising their engineering capacities to dam their respective stretches of the river and harness optimal hydropower.

Story continues below this ad

China has constructed several dams along tributaries of the Yarlung Tsangpo, such as the Pangduo and Zhikong dams on the Lhasa River. In 2014, it completed the Zangmu Dam along the main stem of the Yarlung Tsangpo. The Indian government, too, has expedited the clearance of big dams along the YTB and its tributaries.

Although Beijing has assured India that dams along the Chinese stretch of YTB would have no downstream transboundary impacts, India remains vigilant and anxious. “Perhaps even more concerning to Indian officials than Chinese dams along the YTB,” argues Rampini, “is China’s controversial multi-billion-USD plan to divert water from its southern regions to its more arid regions, a project known as the South-North Water Transfer.”

Colonial roots

According to Rampini, the case is further complicated by the fact that the river crosses one of the disputed boundaries between India and China — the McMahon Line, which separates the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh from Tibet. The McMahon Line was negotiated in 1914 by representatives of the new Republic of China, the Tibetan government, and the British government.

India and the international community continue to recognise it as the legal border between North-east India and the current-day Tibet Autonomous Region of China. However, since gaining control over Tibet in the mid-20th century, China has contested the border, arguing that Tibet was not an independent state at the time of the treaty, making it invalid. This has led both China and India to establish a permanent military presence on their respective sides of the contested line and, in 1962, the border became the site of the last India-China war.

Story continues below this ad

Climate change necessitating cooperation

“The Brahmaputra, or Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet, is counted among the world’s ten major rivers,” asserts Arpi. Rampini adds that there is also no major international water treaty governing the YTB. Bangladesh, as the lowest riparian country in the basin, feels the most threatened, experts say.

Scholars argue that cooperation over the management of the Yarlung Tsangpo, or Brahmaputra, is vital now, given the impact of climate change. “The flows of the YTB and the ferocity of its floods are highly dependent on the melting of Himalayan snow and ice,” says Rampini. As human activities drive up surface temperatures, the Himalayas could experience between 15% and 78% glacier mass losses by 2100. Rampini explains, “As glaciers retreat, glacier-fed rivers such as the YTB will first experience an increase in runoff, as more glacial melt swells their flows.” While this may cause monsoon floods now, the long-term repercussions are worrisome.

“In the long term, as glaciers continue to shrink, the YTB could experience a near 20% decrease in mean upstream water supply between 2046 and 2065, threatening the livelihoods of communities that rely on the YTB flows,” writes Rampini. Additionally, lesser river water will weaken the Chinese and Indian dam-building efforts along the YTB, since hydroelectricity generation depends on river flow.

The YTB river system ties together the fates of China, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. Scholars warn that unchecked dam-building efforts along the Yarlung Tsangpo and the current mega project may eventually lead to a possible ‘water war’ between the two nations.