Alice was in Wonderland. Was maths with her?

Lewis Carroll's absurd universe may hold traces of his beliefs as a mathematics professor at Oxford. Marrying logic with imagination, he was also a prolific creator of puzzles.

Lewis Carroll's vivid puzzles come as no surprise to those who have read the fever dream that is 'Alice in Wonderland'.

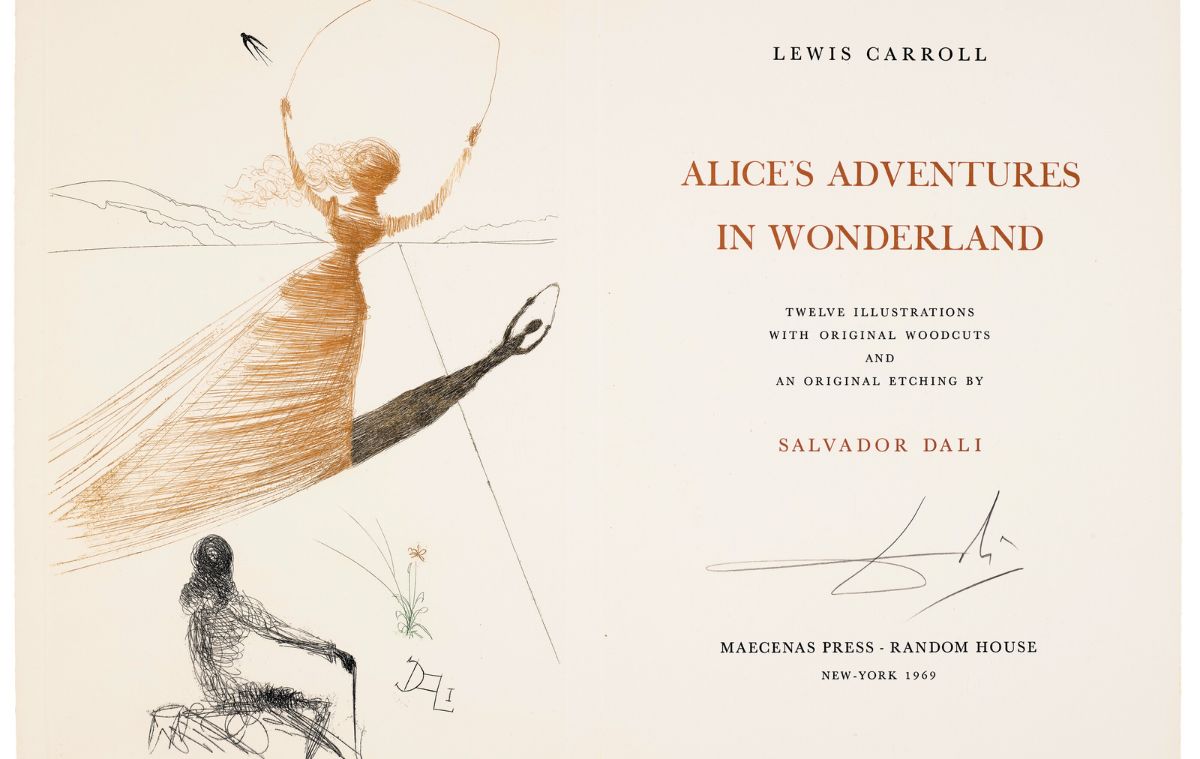

Lewis Carroll's vivid puzzles come as no surprise to those who have read the fever dream that is 'Alice in Wonderland'.In Salvador Dali’s illustrations for a book published by Maecenas Press-Random House, cool colours characteristically bleed into fiery red and yellow. Creatures melt into the paper, eyes pop out, and caterpillar skin glistens against a brown bridge. One sharper figure — that of a girl named Alice — is unassuming, armed only with a skipping rope and her shadow. She appears in different sizes, just like in the story of ‘Wonderland’, but in the art, it’s never a size big enough to steal your attention. Her hands always stay in the air, her legs permanently below.

On both cover and page, Alice is meant to be someone who tries to make sense of the absurdity around her. She and her creator, Lewis Carroll, had more in common than you think.

Dali’s cover art for ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ (Courtesy Maecenas Press-Random House)

Dali’s cover art for ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ (Courtesy Maecenas Press-Random House)

This edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published in 1969, which followed long after the original book’s sequel Through the Looking Glass. These titles have globally resonated as the most popular example of “nonsense literature”, seemingly meaning to evoke childish joy, as readers follow Alice in increasingly befuddling worlds of obstinate creatures, topsy-turvy paths, frustrating riddles, and everyone being “all mad here.”

But Carroll, whose real name is Charles Dodgson, was a mathematician. Growing up in Cheshire village in Victorian England, he spent a lifetime studying logic. His obsession with maths-ridden puzzles began as a child in a village in Cheshire, trying to come up with riddles to amuse himself. He eventually even became a professor of mathematics at Oxford.

The stories of Alice had emerged as tales he would tell one Alice Liddell and her two sisters, the daughter of his college’s Dean. This real-life Alice is rumoured to have inspired his protagonist. At the time, neither the iconic Cheshire Cat nor the Mad Tea Party featured in them. Since then, the journey Alice went through until publication has led several scholars and critics to speculate on what subliminal themes might have emerged in his stories.

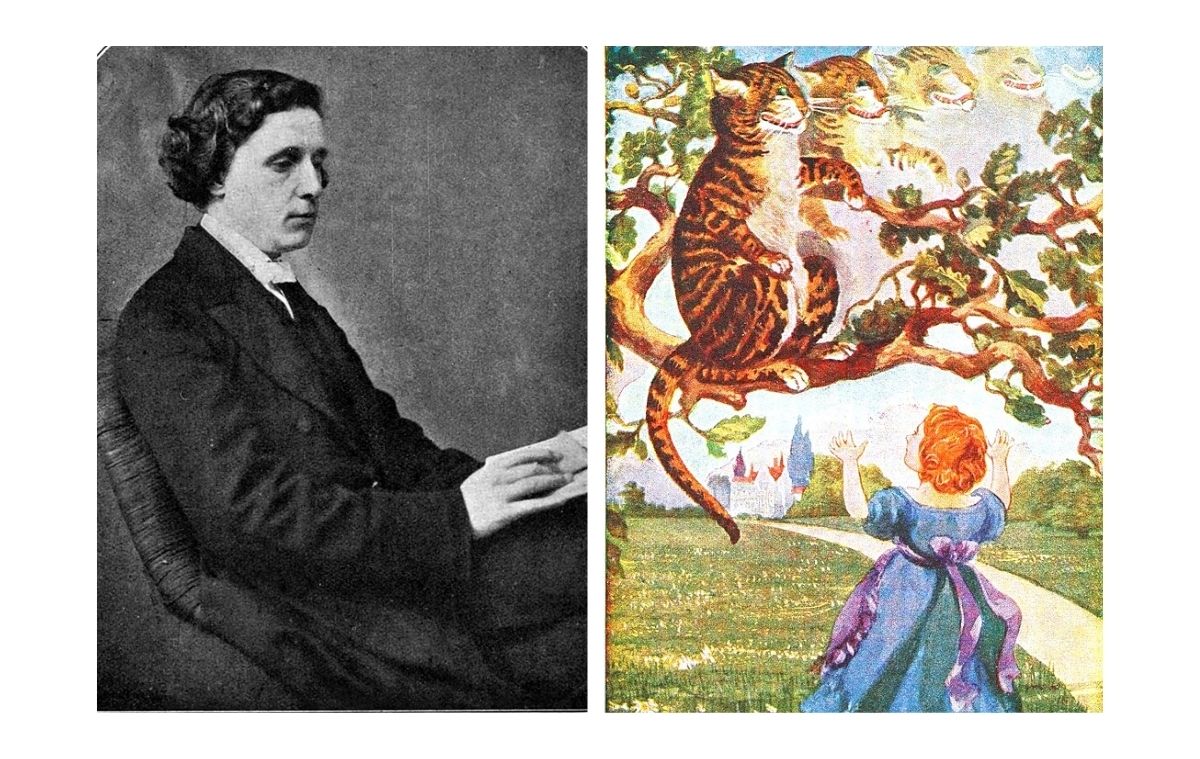

A young Lewis Carroll; and (right) the Cheshire Cat meets Alice in a 1917 retelling.

A young Lewis Carroll; and (right) the Cheshire Cat meets Alice in a 1917 retelling.

Could the ‘nonsense’ in Alice allude to strides in maths?

While some thought that the nonsensical rules of Alice’s worlds might have been commentary on Victorian social rules for prim and proper children, others infer that they tell a coming-of-age tale for young people across the world. Still more critics rubbished both these theories, saying that after all, the stories are “nonsense”.

Not Melanie Bayley.

A scholar of literature, Bayley noted in 2009 that the century in question saw the emergence of imaginary numbers, such as for algebra, in mathematics. This was one of many “controversial” topics that were turbulent for the field at the time, she wrote.

Lewis Carroll, a conservative academic, bitterly opposed the idea of imaginary numbers, calling them “illogical” and even “bizarre”. Midway through the century, several theories around mathematics would prop up across the world, many of which prove reliable today. But Carroll would laugh at and satirise these in his books — as per Bayley’s argument.

Bayley’s theories have been contested by other mathematicians. However, in his academic work, Lewis Carroll’s near-worship of Euclid meant that he often used the Greek scholar’s principle of reductio ad absurdum — taking logical premises to their extreme — to criticise more abstract topics in vogue, such as the principle of continuity.

The Mad Hatter would ask questions like ‘why is a raven like a writing desk?’. Were his riddles meant to be Carroll, a conservative thinker, mocking more abstract forms of maths?

The Mad Hatter would ask questions like ‘why is a raven like a writing desk?’. Were his riddles meant to be Carroll, a conservative thinker, mocking more abstract forms of maths?

Midway through the 19th century in France, continuity emerged to suggest that a shape can be “stretched” into another shape, as long as it retains its most basic properties. For example, a circle “can” be a parabola. Bayley argues that in Chapter 6 of Alice — Pigs and Pepper — the Cheshire Cat’s nonchalance to a baby turning into a pig leaves Alice wildly confused for a reason. Here, she supposedly represents a logician’s view — Carroll’s — to the “absurdity” of imaginary mathematics. All other things being equal, the pig did resemble the baby, but could they truly be treated as equals?

Carroll’s outrage at such ‘loose’ new forms of logic, which he found ‘unteachable’ to undergrads, continues in the Mad Hatter’s tea party. The scene satirises the work of Irish mathematician William Hamilton, whose discovery of a mechanics concept called ‘quaternions’ felt like silly conjecture to Carroll. Quaternions normally relied on three terms, the concept existing on a flat plane, but Hamilton would add a fourth term, Time, to allow it to operate in 3D space. Carroll’s rejection of this theory appears in the form of the White Rabbit, who is always stressed about a lack of time. His persona contrasts with the March Hare, the laid-back host of the tea party, which — take note — only has room for three.

In the story, the White Rabbit’s panic is because the Red Queen may take his head for being tardy.

In the story, the White Rabbit’s panic is because the Red Queen may take his head for being tardy.

Kashmiri mathematics professor Firdous Ahmad Mala expanded on Bayley’s arguments. “Four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is — oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate!” exclaims Alice at one point in the novel. Mala traces this line back to Carroll’s dislike of the use of arithmetic when “switching over to base representations other than that of the decimal one”.

Largely, Carroll’s rebellion was against mathematics that was disconnected from nature. The irony is not lost on readers, though, that as a guardian of Classical thought, he would ultimately create a wildly imaginative, hallucinatory and rule-breaking world of his own. British mathematician Keith Devlin tells NPR that the core message in Alice is to “get rid of all of this complexity in the first place, and let’s just go back to the familiar old geometry that we’ve had since Euclid for 2,000 years.”

Many mathematicians have opposed this line of analysis. Luckily, Carroll tried his best to leave behind universal riddles for the world to solve outside of his children’s books. In fact, towards the end of his life, he attempted to write a book that entirely comprised the same, but he died before he could finish it. In 1992, an incomplete draft was published by Dover Publications as ‘Lewis Carroll’s Games and Puzzles’. And some of the riddles are curiously named — such as Alice’s Multiplication Tables and Looking-Glass Time. You can explore these games via the PDF at the end of this article.

Dive into Lewis Carroll’s riddles

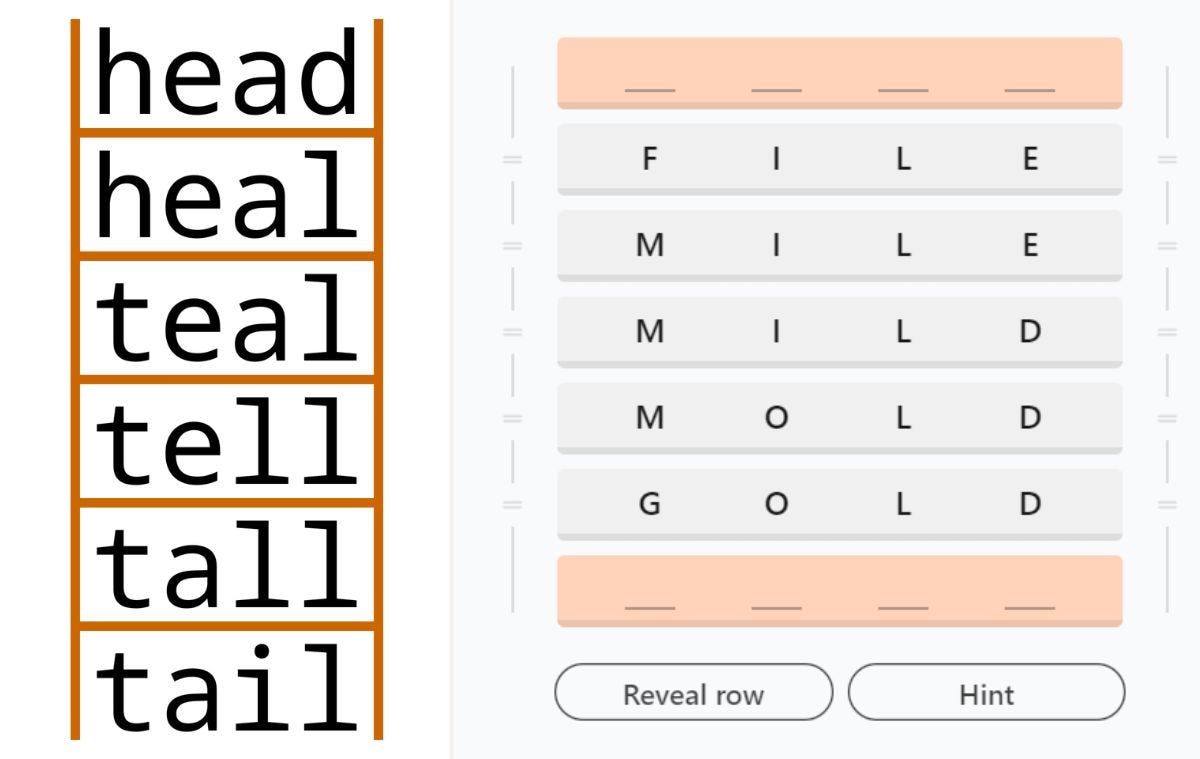

Lewis Carroll’s brainteasers are well-documented, having been recirculated for decades in periodicals, newspaper columns and game societies. He is largely agreed as the mind behind ‘word ladders’ (published as ‘doublets’ by Vanity Fair) where the goal is to transform words by changing one letter at a time. A modern version of this is Crossclimb, found on LinkedIn Games.

Lewis Carroll’s original word ladder puzzle; and (right) Crossclimb as seen on LinkedIn.

Lewis Carroll’s original word ladder puzzle; and (right) Crossclimb as seen on LinkedIn.

Lewis Carroll also penned countless ‘logic challenges’, i.e. word problems similar to what you might find in a reasoning exam. He would note these challenges in his diary over a lifetime, as and when they would occur to him. The subject matter, of course, is kept light, sourcing elements from literature, nature and everyday life. Professor GN Hile of the University of Hawaii explains how to approach these puzzles:

“In each puzzle you are to write the assertions symbolically as implications, along with their contrapositives, and then string together with arrows all the assertions to arrive at a final conclusion. Your answer will be an ultimate implication, which you must then cleverly translate back into ordinary language.”

In short, make judgments using the data available to find an undeniable statement. Here are three of Lewis Carroll’s problems, in increasing difficulty:

Puzzle 1

No ducks waltz.

No officers ever decline to waltz.

All my poultry are ducks.

Puzzle 2

Things sold in the street are of no great value.

Nothing but rubbish can be had for a song.

Eggs of the Great Auk are very valuable.

It is only what is sold in the street that is really rubbish.

Puzzle 3

All writers, who understand human nature, are clever.

No one is a true poet unless he can stir the hearts of men.

Shakespeare wrote “Hamlet”.

No writer, who does not understand human nature, can stir the hearts of men.

None but a true poet could have written “Hamlet”.

More of these puzzles, known as polysyllogisms, can be found in ‘Lewis Carroll’s Symbolic Logic’ (1896). The free e-book is hosted by Project Gutenberg.

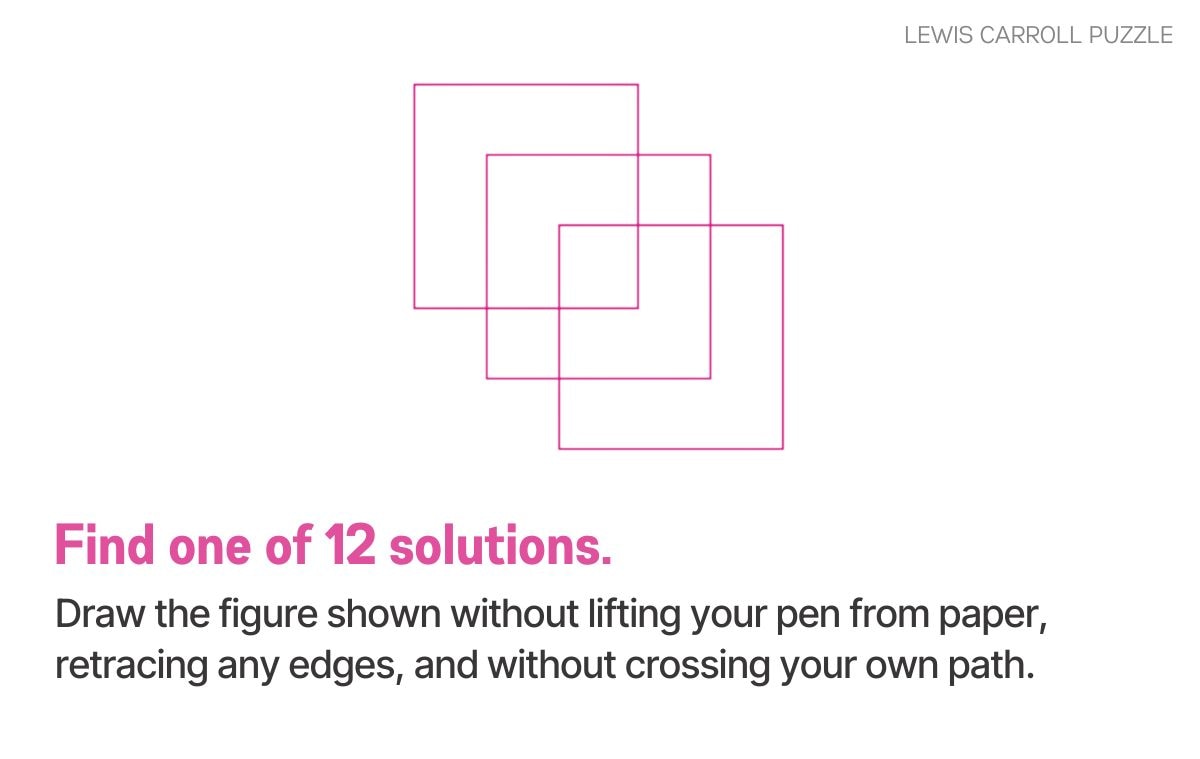

Carroll also devised visual puzzles, as well as activities meant to entertain night owls as they searched for the “elusive rabbit-hole of a good night’s sleep”. Conjuring ghosts and ‘calming calculations’ are some options you might mull from his ‘Guide for Insomniacs’ (2024; a 1979 reissue), but for something more straightforward, try this rectangle puzzle:

Rectangle logic puzzle by Lewis Carroll. Can you uncover all 12 possibilities?

Rectangle logic puzzle by Lewis Carroll. Can you uncover all 12 possibilities?

From Dover’s ‘Lewis Carroll’s Games & Puzzles’ (1992), you can enjoy Wonderland-themed ‘verse riddles’ as well as the author’s take on some universal brainteasers. Enjoy a limited preview of this book below, courtesy Google Books:

For more brainteasers, quizzes and general nerdy goodness, we invite you to visit Express Puzzles & Games. Follow @iepuzzles for contest alerts!

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05