Rewind & Replay | The Satanic Verses: Why it was never just about the book

How a Rajiv Gandhi government, cornered from all sides, brought in the ban; and how it played out for years later.

THE 37-year history of the ban in India of Salman Rushdie’s book The Satanic Verses has never been far from the politics of the day. So much so that, come 2022, despite how distant it claims to be from the ideology in power in 1988 — when The Satanic Verses was banned — the Modi government has found it prudent to keep silent on the grievous attack on the India-born writer.

The ban was announced by the Rajiv Gandhi government on October 5, 1988, less than a fortnight after the release of the book. Nobody had read it at the time, including by all accounts the leader who was at the forefront demanding the ban – Syed Shahabuddin of the Janata Dal.

However, the Indian Prime Minister, originally hailed as the youthful promising face who would lead the country into an era of modernity, was more than receptive to the call for a ban, for various reasons.

First, the country was still bruised from the violence of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. While Indira Gandhi’s assassination had propelled Rajiv to what remains the biggest parliamentary majority in India’s history, the taint of the violence that followed the killing marred its golden start.

This meant that the young, relatively immature PM found himself easily malleable to pressures, particularly on the religious front.

In its very first year, came a turning point for the Rajiv government. At the heart of it was an unlikely 67-year-old woman, Shah Bano, who back in 1978 had approached the Supreme Court demanding maintenance from her husband, a noted lawyer, after divorce. On April 23, 1985, the Court ordered that alimony be paid to her.

As Muslim groups held protests against what they called the intereference in their personal laws, a nervous government passed the Muslim Women (Protection on Divorce Act), 1986, circumventing the SC verdict by easing the liability on a Muslim husband to pay maintenance to his divorcing wife. Among those severely critical of the move was one of Rajiv’s own ministers, Arif Mohammed Khan, who quit in protest.

When the Hindu groups, particularly the BJP, protested at this blatant “Muslim appeasement”, the Rajiv government countered by rushing into another controversial decision months later.

On February 1, 1986, it got the Muslim side to acquiesce to the removal of locks from a structure in the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri mosque site in Ayodhya, where idols had been played surreptitiously in 1949.

Arif Mohammed Khan claimed in an interview that there was a quid pro quo with the All India Muslim Personal Law Board on the matter. “In the second week of January 1986, the then Prime Minister announced the decision to accept the demand of the AIMPLB (All India Muslim Personal Law Board) to reverse the judgment of the Supreme Court in the Shah Bano case, and the blowback was so severe that the government felt the need to do some balancing act and the unlocking was done on February 1, 1986,” he said.

Until 1985, a priest was allowed to perform puja at the disputed site once a year. After the removal of the locks, all Hindus got access to the site.

By 1987, the Congress government was further weakened, in the wake of the Bofors scandal, with allegations of payoffs going right up to Rajiv. His Defence Minister, V P Singh, resigned over the scandal, further putting pressure on the regime.

A leader from Uttar Pradesh, Singh went on to project himself as the protector of Muslims as he mounted a challenge to the Congress as a Janata Dal leader. The Congress was also under pressure from a resurgent BJP, which had latched onto the Ram temple dispute to whip up popular support.

In July 1988, hemmed in from all sides, the Rajiv government introduced an anti-defamation Bill, which was widely criticised for trying to censor the media for criticism. In one of his most embarrassing moments, Rajiv had to withdraw the Bill, after it had already been passed by the Lok Sabha, in September 1988.

The Satanic Verses dropped in at this moment, in the middle of September 1988. The provocation to seek the ban were excerpts from the book carried by a magazine in India, along with an interview of Rushdie.

Janata Dal MP Syed Shahabuddin and others chanced upon the excerpts and a furore ensued. Calling it “a deliberate insult to Islam”, Shahabuddin held that it was “not an act of literary creativity”. Congress MP Khurshid Alam Khan also sought a ban, saying while he agreed with freedom of expression, “that does not mean that you hurt somebody’s feelings”.

By late September, a variety of Muslim leaders, across parties, had come together to seek a ban. Home Minister Buta Singh, who was trying to persuade some of them to call off a threatened march to Ayodhya over the Babri dispute, was desperate for a way out.

On October 5, 1988, the government banned the book, via a Customs order by the Finance Ministry. Later, that would provide a flimsy fig-leaf that it was not the book that was banned, but just its import.

Rushdie, in an open letter to Rajiv Gandhi, accused him of capitulating to a handful of Indian Muslim politicians and clerics who were “extremists”. “The right to freedom of expression is at the foundation of any democratic society, and at present, all over the world, Indian democracy is becoming something of a laughing-stock,” he wrote.

Criticising the ban, veteran Congress leader Badruddin Tyabji said: “It seems suspiciously like a coup de theatre in a comedy played by a group of deaf actors under the direction of a blind director. The blind have not read the script and the deaf only understand the sign language of the election-hustings.” He added that the consequences were likely to be “exactly the contrary of what they proclaim”, that pirated editions will flourish and many more will read the book than would normally have.

Speaking to the media recently, in the wake of the attack on Rushdie, Natwar Singh, who was the external affairs minister at the time of the ban on the book, justified it. He said when PM Rajiv Gandhi asked him what he thought about banning the book, he told him: “All my life I have been totally opposed to banning books, but when it comes to law and order, even a book of a great writer like Rushdie should be banned.”

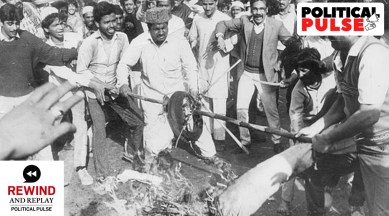

The violence followed later, though, after the ban by India prompted similar steps by other countries, leading up to the fatwa by Iran Supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini. In February 1989, some 10 days after the fatwa was announced, 12 people were killed in Bombay, as police opened fire to check a mob of around 10,000 Muslims protesting outside the British Consulate. In Kashmir, a person was killed and over 100 injured in anti-Rushdie riots in Srinagar.

In 1989, driven further into a corner by the BJP’s rising campaign and the approaching elections, the Rajiv government allowed shilanyas at the Babri disputed site, involving laying of the first stone for temple construction. By December 1992, the Babri mosque had been razed.

The Satanic Verses row would flare up again, in April 1992, when a violent agitation was launched at Jamia Millia University against Professor Mushirul Hasan, who had earlier that year been appointed as Pro-Vice Chancellor of the institution. In an interview to Louise Fernandes, a journalist and the wife of Congress leader and Union minister Salman Khurshid, Hasan said that though he agreed that The Satanic Verses had greatly hurt Muslim sentiments, he was in principle opposed to the banning of books. Khurshid is the son of Khurshid Alam Khan, one of the first Congress leaders to seek a ban on The Satanic Verses.

For eight months, Hasan, one of India’s finest pro-Independence historians, was not able to step on campus. On December 4, 1992, when he returned on the specific instructions of the Vice Chancellor, after a Central Government-appointed committee “exonerated him of all charges”, Hasan was brutally assaulted by a section of students. The violence was suspected to have been engineered by politicians. By April 1993, Hasan told an interviewer, he could not even perform his functions as pro-V-C from his house.

The Narasimha Rao government at the Centre was accused of failing to ensure Hasan could carry out his duties, despite Jamia being a Central university.

In June 2004, after the UPA government came to power under Manmohan Singh, Hasan was appointed the Vice-Chancellor of Jamia Millia, his successful tenure earning him the moniker among students of ‘Shah Jehan of Jamia’.

In 1995, it was the turn of another Rushdie book to be caught up in politics – The Moor’s Last Sigh, chronicling, on the face of it, the history of an Indian family over several generations. The Shiv Sena, the ruling party in Maharashtra, banned the book in the state before it could begin selling there, for parodying its supremo Bal Thackeray, through a character clearly based on him.

“The Shiv Sena will not let the book exist,” said Pramod Navalkar, the Maharashtra Culture Minister at the time.

In 1989, the same Bal Thackeray had expressed outrage over the Congress government’s ban on The Satanic Verses, arguing that it was “a free country” and that Muslims should bear this in mind.

Not only did the Rao government let the Maharashtra ban on The Moor’s Last Sigh go ahead, it unofficially banned further imports of the Rushdie novel. Publishers Rupa & Co. finally approached the Supreme Court. In February 1996, the Court ruled the ‘ban’ on the book as unconstitutional.

In November 2015, senior Congress leader P Chidambaram, the Minister of State for Home at the time of the ban on The Satanic Verses, said it had been a wrong decision.

Two days later, then Congress spokesperson P L Punia again argued that the book was never banned, “only its import”. He also suggested that it were the publishers of the book, Penguin, who had decided not to print and sell it, and the government had no role to play.

In 2019, the Shah Bano case finally saw some addressal in the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Bill, brought in by the Modi government, banning instant triple talaq.