Long before the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) became a reality, they were the nowhere people of Partition who became the celebrated new citizens of India.

Nine years later, living up to 25 people in two-bedroom apartments, with property papers still not transferred to them, awaiting promised cash doles, and lacking job options, they say they want to return across the border.

Children at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district. The residents of this area used to stay at Darsiar Chora enclave.

Children at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district. The residents of this area used to stay at Darsiar Chora enclave.

On April 19, as Cooch Behar votes in the first phase of the Lok Sabha elections, on the electoral rolls will be the 15,421 people who became Indians over a period after Delhi and Dhaka signed a historic land boundary agreement in 2015 covering their respective enclaves lying in each other’s territories.

Story continues below this ad

It will be their second tryst with general elections. In 2019, the BJP had won an overwhelming victory from here. However, their numbers, at 15,421, mean these ‘new residents’ remain on the margins of the poll campaign – amidst all the CAA talk.

Villagers at Madhya Masaldanga.

Villagers at Madhya Masaldanga.

As part of the India-Bangladesh agreement, 111 ‘Indian’ enclaves spread over 17,160 acres inside Bangladesh went to Bangladesh, while 51 ‘Bangladeshi’ enclaves occupying 7,110 acres in India became the property of India. The residents of these enclaves were given the option of accepting citizenship of either country.

Eventually, while 921 crossed over to this side with much fanfare, 14,500 residents of formerly Bangladeshi enclaves were identified as Indians.

Both say their plight is no better – if not worse – though the residents of former Bangladeshi enclaves concede they “at least have roads now”.

Story continues below this ad

The 921 who lived in ‘Indian’ enclaves in Bangladesh who came to India in phases were initially kept in makeshift tin-roof camps on open grounds in Dinhata 1 Block of Cooch Behar district.

After five years of tortuous summers and monsoons spent in these accommodations, in 2020, the state government moved them into three apartment clusters with funds provided by the Centre. While one of these clusters is located in Dinhata Block, the other two are in Haldibari and Mekhliganj blocks of Jalpaiguri Lok Sabha seat, which also votes on April 19.

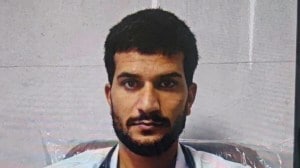

Kashem Ali at his room at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district.

Kashem Ali at his room at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district.

Kashem Ali, 65, has now been sharing his two-room apartment in Dinhata with his family of 22 for three years. There are 58 families, same as his, living in this cluster, all of whom came from Kurigram district in Bangladesh.

All of Kashem’s five sons are migrant labourers, earning daily wages in places like Delhi, Haryana, Gujarat, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Story continues below this ad

Says Kashem: “When we came, we were assured we would be rehabilitated, given the same amount of land as we had in Bangladesh and get employment, apart from Rs 5 lakh per family. None of that has happened.”

The Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress government provides 21 kg of rice and 14 kg of wheat per family per month under the rehabilitation scheme.

The Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress government provides 21 kg of rice and 14 kg of wheat per family per month under the rehabilitation scheme.

All they got are the apartments, Kashem says, which accommodate on an average 12 people in two rooms. “We were also given voter identity cards, ration cards and job cards (NREGS). But we don’t need apartments, we need land… We want cow sheds to keep cows, area to plant trees… And while we have job cards, we haven’t got any (MNREGS) work since 2017. All we get is some free rations,” says Kashem.

The Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress government provides 21 kg of rice and 14 kg of wheat per family per month under the rehabilitation scheme.

Kashem’s neighbour Anukul Burman says he left behind 10 bighas of land in Bangladesh. Now, he too ekes out a living as a daily wager. “We thought we will have a new life in India, good jobs, land to till and a proper house. But, now we think we made a mistake and want to return to Bangladesh. At least we will try to get back some of our land there. I could not sell my land when I came to India,” says Burman.

Story continues below this ad

Krishna Adhikari (36), who works as an e-rickshaw driver, says he too left land behind in Bangladesh, and got no compensation for the same. “We have approached the BDO (Block Development Officer), SDO (Sub-Divisional Officer) and DM (District Magistrate), but nothing has happened.”

Villagers at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district

Villagers at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district

After clarifying that he has been here only a few months, DM Arvind Kumar Meena says: “The files I have seen indicate that the funds provided for rehabilitation have been utilised. Secondly, the demands they are making, all were not officially promised. However, in case of any specific complaints, they are welcome to approach us and we will do the needful.”

In the absence of jobs, most of the youths have migrated to other states for menial work.

“You can check for yourself, you will find only one or two youngsters here,” says Lovely Bibi, 35, a mother of three, whose husband has been travelling for work to other states.

Story continues below this ad

What has added to their uncertainty, the residents say, is that they have not got documents for even the apartments they moved into.

“Initially, government teams would come and offer facilities such as health check-ups. But gradually all this stopped,” says Muhammed Khondkar, 63.

Helena Begum holding her Job card at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district.

Helena Begum holding her Job card at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district.

The case of Saddam, 30, is a little different, as he is a resident of Madhya Masaldanga, one of the former Bangladesh enclaves located in Dinhata 2 Block. “I can remember the day when our enclave was assimilated in India,” he says. “We realised for the first time what a country meant. We were neither Bangladeshi nor Indian before. We could not go to a government school or hospital in India, and had to adopt false names. Now we are Indians, we also have a voter card.”

However, they too are yet to get the final papers for the land they have been settled on for years. Says Jainal Abedin, 30: “There was a survey but the land papers handed out were incorrect. For example, I have 5 bighas, of which 1 bigha was registered under my neighbour’s name.”

Story continues below this ad

A district land official in Cooch Behar admits there are issues. “We are working on this, and expect a solution soon,” the official says.

A boy at Madhya Masaldanga.

A boy at Madhya Masaldanga.

But such promises hold little hope in the absence of any political heft. Bibi points out that no party has come to them seeking votes, or offering assurances to solve their issues. “Only in the panchayat polls last year did some politicians come. It does not matter whether we vote, or whom we vote for.”

The BJP has re-fielded sitting MP and Union Minister of State Nishith Pramanik from Cooch Behar, while the TMC has put up its 2021 Assembly poll candidate, Sitai Jagadish Chandra Burma Basunia. The Forward Bloc’s Nitish Chandra Roy is the Left Front candidate, but their electoral ally Congress also has a nominee here in Pia Roy Chowdhury.

In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP had won by around 1.5 lakh votes. In the 2021 Assembly elections as well, all seven Assembly seats of Cooch Behar were won by the BJP.

Story continues below this ad

The CAA, the residents know, is a BJP showcase initiative, particularly for Bengal. Even if it doesn’t apply to them, it has left them disconcerted. The CAA promises expeditious citizenship to “religious minorities” from neighbouring countries, including Bangladesh, who have crossed over before December 2014.

Residents of Madhya Masaldanga, one of the former Bangladesh enclaves located in Dinhata 2 Block.

Residents of Madhya Masaldanga, one of the former Bangladesh enclaves located in Dinhata 2 Block.

“We became Indian citizens in 2015… We are unsure of how we will be treated under the Act,” says Rahim Ali, 53, a resident of the Madhya Masaldanga enclave.

Hence, Kashem believes he has a solution, in another BJP promise he has heard about: a National Register of Citizens (NRC), to “weed out illegal immigrants”. “Amader NRC kore Bangladeshe pathiye dik (Use the NRC and send us back to Bangladesh),” he says. “We will be saved.”

Children at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district. The residents of this area used to stay at Darsiar Chora enclave.

Children at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district. The residents of this area used to stay at Darsiar Chora enclave. Villagers at Madhya Masaldanga.

Villagers at Madhya Masaldanga. Kashem Ali at his room at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district.

Kashem Ali at his room at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district. The

The  Villagers at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district

Villagers at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district Helena Begum holding her Job card at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district.

Helena Begum holding her Job card at Dinhata village 1 in Coochbehar district. A boy at Madhya Masaldanga.

A boy at Madhya Masaldanga. Residents of Madhya Masaldanga, one of the former Bangladesh enclaves located in Dinhata 2 Block.

Residents of Madhya Masaldanga, one of the former Bangladesh enclaves located in Dinhata 2 Block.