Delimitation debate: Amid populous North vs lean South, there are alternatives

Linking delimitation to fertility rates and revenue generation, to variations on proportional representation and reforming the Rajya Sabha, the suggestions over the years.

In the existing delimitation framework, each seat is meant to represent its total population, whether or not they are of voting age or registered as voters in a particular constituency. (Express archive photo/ Partha Paul)

In the existing delimitation framework, each seat is meant to represent its total population, whether or not they are of voting age or registered as voters in a particular constituency. (Express archive photo/ Partha Paul)The debate over delimitation, which is as of now due in 2026, is heating up, with almost all Opposition parties agreeing that population should not be the sole basis to reapportion Lok Sabha seats as it would penalise those states which have managed to bring down their population growth. Several alternatives have been pitched over the years – from linking delimitation to fertility rates, to reforming the Rajya Sabha.

A look at some:

Raising the cap on seats

The simplest solution is increasing the number of seats in the Lok Sabha above the constitutional cap of 550 to ensure there is parity across the country in terms of population per seat.

As per Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson, fellows at US-based think tank Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, projected population figures for 2026 show that the Lok Sabha would need 848 constituencies to ensure reapportioning does not reduce any state’s current seats. One benefit of raising the cap on Lok Sabha seats is that it would help keep the population per seat low, thereby improving representative democracy.

For instance, in 848-seat configuration, while Uttar Pradesh would get 143 seats (up from the current 80), Tamil Nadu would get 49 seats (currently 39).

MAP: Seats in an expanded Lok Sabha.

MAP: Seats in an expanded Lok Sabha.

Rangarajan R, a former IAS officer, argued in a report published by The India Forum, an online journal, that since India’s population will eventually hit a peak and begin declining in the 2060s, the cap on the number of Lok Sabha seats should remain in place. Instead, the number of seats in the state Assemblies should be raised since MLAs work far more closely with their constituents, he said. Rangarajan further called for empowering local bodies through improved devolution of powers and funds to strengthen democracy.

Pranay Kotasthane and Suman Joshi of the Takshashila Institution, an independent research centre, have suggested that UP – given that its size can have a disproportionate impact in Parliament, if the number of seats are increased as per population – be split into three states. Splitting the state would also improve governance and administration for such a large population, they said.

Variations on proportional representation

In the existing delimitation framework, each seat is meant to represent its total population, whether or not they are of voting age or registered as voters in a particular constituency. In many states, people may not be natives of the constituencies they reside in but still count towards the delimitation formula.

To address this discrepancy, an argument has been made to apportion seats based on the number of voters alone. A report published by the Vidhi Centre on Legal Policy, a Delhi-based think tank, said that such a system “may be more legitimate to determine constituency size on the basis of those who can or actually do act to hold representatives accountable in elections”.

However, the report also pitched a degressive proportionality method, under which “more populous states agree to be under-represented in order to allow the less populous states to be represented better”.

Canada, for instance, amended its constitution in 2011 to enact degressive proportionality to find a balance between larger, faster growing provinces and smaller, slower growing ones. “An ideal constituency size for the House of Commons is first determined, and if allocating seats to a province according to that constituency size results in a province having fewer seats than it does in the Senate or than it did in a particular previous apportionment, the shortfall is compensated with additional seats… This ensures a minimum level of representation for smaller provinces while allowing others representation as per their population,” the report states.

In a paper published in the Economic and Political Weekly, S Raja Sethu Durai and R Srinivasan, a professor at the University of Hyderabad and a member of the Tamil Nadu State Planning Commission respectively, found that applying the Canadian system to the Lok Sabha would raise its total strength to 552. For instance, while UP would get an additional nine seats taking it to 89, Tamil Nadu’s seats would remain unchanged at 39.

Accounting for fertility rates

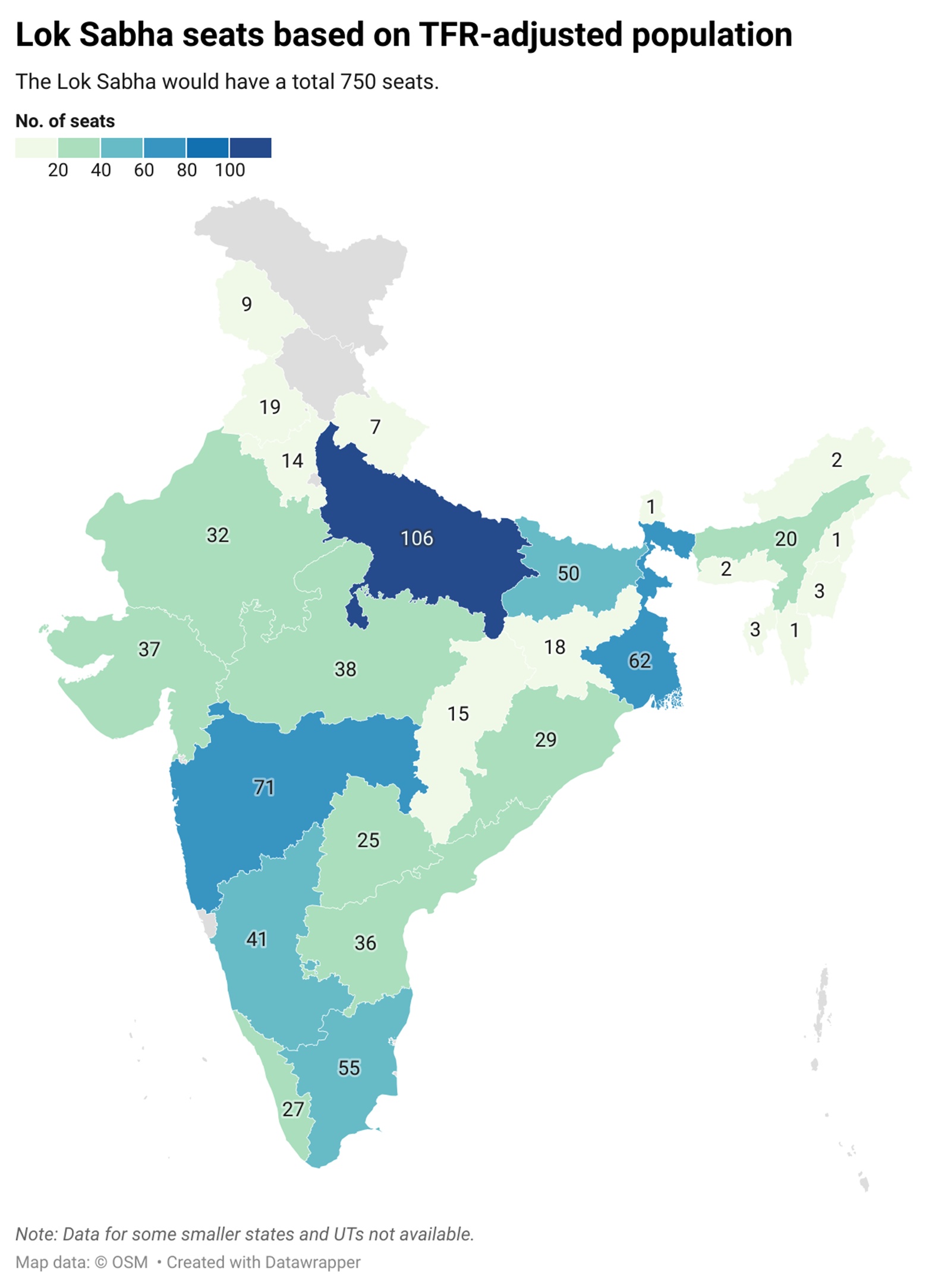

Durai and Srinivasan also argued that total fertility rate (TFR) should be factored into delimitation.

For instance, the Fifteenth Finance Commission, which made recommendations on the devolution of funds to the states for 2021-26, used TFR as a weight to balance against population, ensuring that states that controlled TFR aren’t punished. Using this principle, Durai and Srinivasan devised a formula to calculate TFR-adjusted populations from the 2011 Census.

Their calculations show that while the strength of the Lok Sabha would have to be raised to 750, seats could be reapportioned in a way that does not punish states with slower growing populations. For instance, while Uttar Pradesh would get 106 seats and Bihar would get 50 seats (currently 40), a less populous state like Tamil Nadu would get 55 seats.

MAP: Lok Sabha seats based on TFR-adjusted population.

MAP: Lok Sabha seats based on TFR-adjusted population.

Reforming Rajya Sabha

An argument has also been made for reforms in the Rajya Sabha to help balance out the negative effects of delimitation of Lok Sabha seats.

Under the existing constitutional provisions, noted the Vidhi Centre’s report, seats are allotted in the Rajya Sabha based on a form of degressive proportionality that does not devalue smaller states. “This formula granted states a seat each for every million persons until the first five million and then one additional seat for every additional two million. The scheme ensures the seats-to-population ratio decreases with the size of the state,” the report said.

However, this formula has not been rationalised over time. Currently, the 10 most populous states have 156 of the Rajya Sabha’s 250 seats, and the nine least populous states have one seat each. Using the European Parliament as an example, the Vidhi Centre suggested setting a minimum and maximum number of seats per state and allocating the seats in a way that does not disenfranchise smaller states. “If the minimum is set at five seats and the maximum at twenty, four of the states with the smallest size would still have the same heft as one of the largest states,” the report said.

However, the Rajya Sabha has limited powers and often fails to adequately represent the states. Not only are Rajya Sabha MPs not required to be domiciled residents of the states from where they are elected by the Assemblies, but the Upper House also does not have a say on Money Bills, which focus on financial legislation like the Budget.

To get around this, it has been suggested that the Rajya Sabha be an elected body, similar to the US Senate that has two members from every state, to balance out the population-proportioned seats in the Lok Sabha. However, an elected Rajya Sabha, whether the seats are allotted based on population or each state gets the same number of seats, would not be effective until the Upper House can amend Money Bills and the domicile requirement is reinstated.

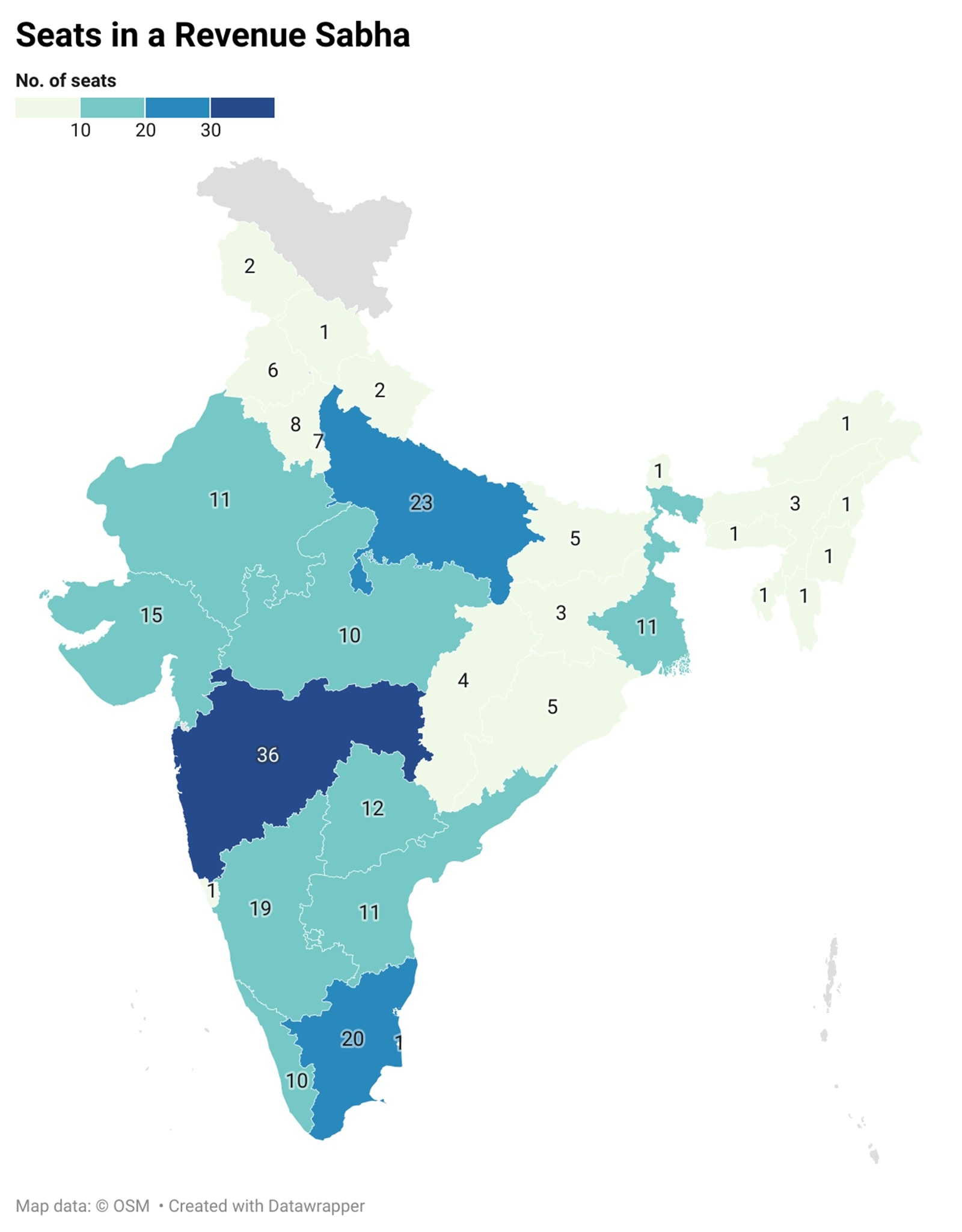

One suggestion is to convert the Rajya Sabha into a “Revenue Sabha”, as per Shruti Rajagopalan, a research fellow at George Mason University in the US.

MAP: Seats in a Revenue Sabha.

MAP: Seats in a Revenue Sabha.

Rajagopalan argued that fiscal federalism should be at the centre of delimitation. Given varying capacities across states to raise revenues and fund expenditures, the Union government devolves funds on a needs basis. Wealthier southern states with smaller populations contribute more to the national revenue pool than poorer states with larger populations, but richer states end up with smaller shares of central funding.

Since the Lok Sabha alone can pass Money Bills, “fiscally centralised system only punishes wealthier southern states through a reduction of proportional seats in the Lok Sabha”, Rajagopalan argued.

In Rajagopalan’s Revenue Sabha model, the Upper House would be completely redesigned based on states’ Own Revenue Per Capita (ORPC) to complement the population-based Lok Sabha. ORPC measures a state’s revenue raising capacity.

In a Revenue Sabha, each state would be allotted seats based on its ORPC compared to the national average, in addition to its population. For instance, UP currently has 31 Rajya Sabha seats, which would go up to 40 seats if allocated based on the current population. However, UP’s ORPC is Rs 5,050, compared to the national average of Rs 8,771. Using the ratio of UP’s ORPC to the national average, Bihar would be allotted 23 seats in a Revenue Sabha.

Similarly, Tamil Nadu’s ORPC of Rs 13,565 is more than 1.5 times greater than the national average. While the state has 18 Rajya Sabha seats, which would fall to 13 if allotted based on population, in a Revenue Sabha it would have 20 seats.

In effect, a Revenue Sabha would favour states capable of raising their own funds while incentivising economically weaker states to improve their revenue raising capacities, thus “aligning political incentives with economic growth”.

However, just as with an elected Rajya Sabha, a Revenue Sabha will also need to have a say on Money Bills.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05