Love stories do not die

We have to find ways to show up for each other in ways that make us stronger and make our connection with the people who have passed on stronger too

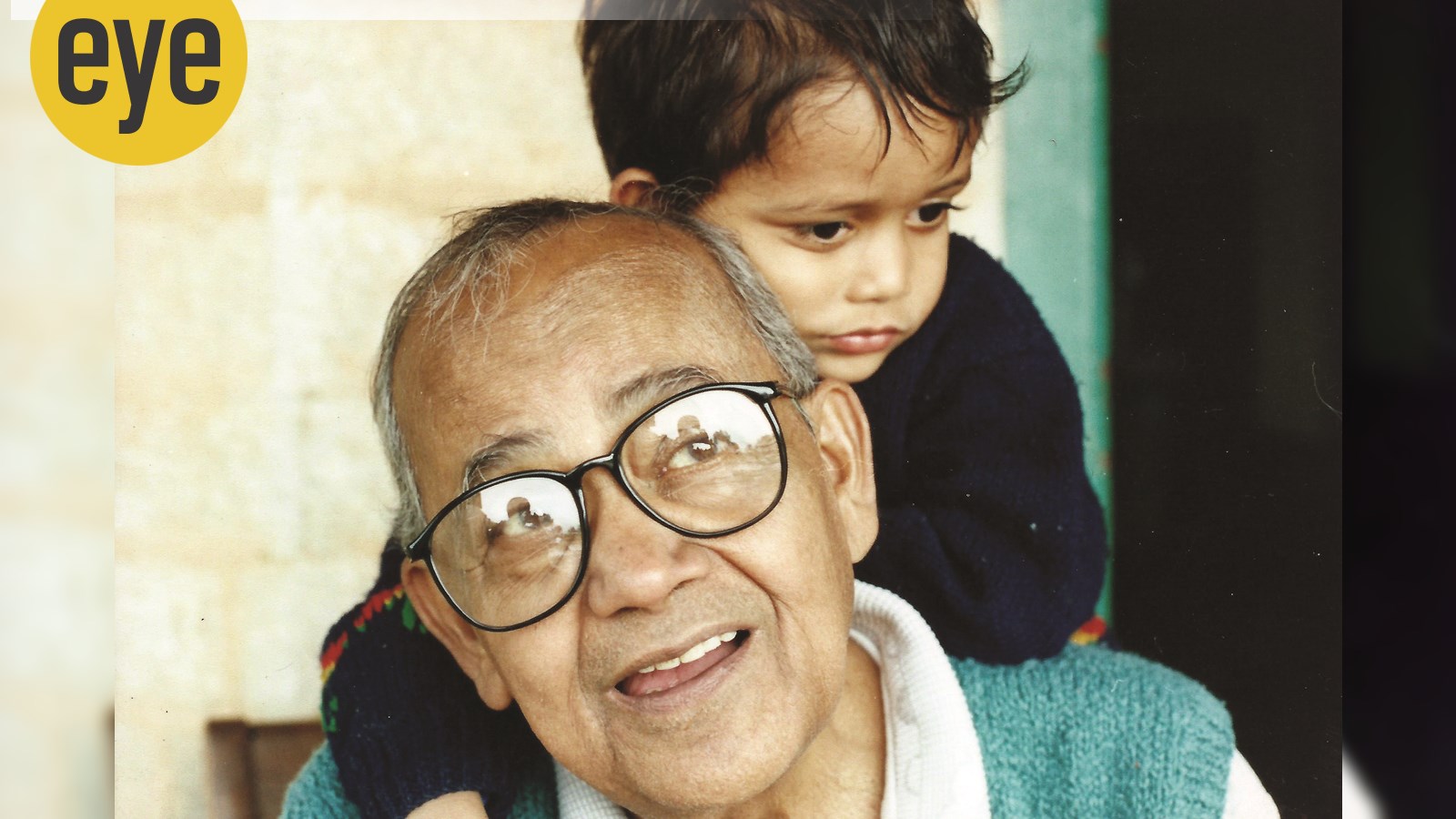

We heal in kinships, not in silos. (Photo credit: Mimi

Chakrabarti)

We heal in kinships, not in silos. (Photo credit: Mimi

Chakrabarti)I got a call in the middle of the night that my father was no more. My husband and I left for my mountain town in the dark and reached home thronging with known and unknown faces. Teary, tender embraces soothed me a little, but it seemed to me as if I was stuck in a swamp. I was back home where I was born, and my father’s body was being prepared for the antim yatra with rituals at the very spot where my marriage rituals were held decades ago. The muddled voices of the priests did not make any sense to me until I heard them instruct someone to get my mother to make the parikrama of her beloved husband’s body and break her bangles on the arthi. Shaken out of my stupor, I spoke up and told the priest, “Nahi, aisa bilkul nahi hoga” (No, this will not happen at all). The priest, not used to being disregarded, and definitely not by a woman, told me that it was a parampara and only symbolised that their relationship was now over. I stood my ground and the rituals were completed but his words have kept painfully ricocheting in my head.

If personal is political then death is political, too. Patriarchy hurts and in times of pain, it adds to the anguish. A few years ago, a friend had shared with me about how after her father’s death she had felt more invisible than ever. It was her brothers, with the priests, who made the decisions and carried out the rituals where women were just expected to follow them without any questions. Any protest would be seen as degrading the parampara. “It was very confusing as I was dealing with the loss of my father and my position in the family at the same time.” What is it about death that silences us and robs us of values that we uphold so high otherwise?

Let me clarify that this is not to say that parampara does hold importance for me. We are who we are because of the cultural context we grow up in. It is our traditions, our heritage and our rituals that give us a sense of belonging, connection and continuity from one generation to another. After my father’s death, that is what sustained us. We heal in kinships and not in silos. Our family has been there for generations and our roots spread to many towns and villages near and far. People kept pouring in day after day. Subdued conversations would inevitably lead to laughter, tears, endless cups of tea and even more endless stories. Stories of my father that I had never heard before, made me get to know him in ways that I had never known before. It reminded me of Tagore’s song “Tomay notun kore pabo bole” – I lose you to find you again and again. As stories of past, present and possible future were being weaved, back and forth until what the Stoics called the chronos (sequential) time melted into aeon time – fluent looping back and forth gave way to a fascinating sense of timelessness and eternity.

We make stories and stories make us. We make sense of this world through stories; they give our life meaning, and they give meaning to our death. Stories transcend death, love stories transcend generations and become legacies. And through stories of legacies, people live with us forever.

So yes, parampara is important but not sacred. It cannot be at the cost of the human spirit and connections; where it becomes a weapon for power play, oppression and alienating people because of their gender, caste, religion, class or sexuality. Then we need to stand up to it, in solidarity, and call it by its name. And no, my father’s death does not mean that my mother’s or my brother’s or my relationship with him has ended – it will transcend time and live with us and beyond us. Death robs us of a lot, but it can never take away our memories and our stories.

Because love does not die, relationships do not die, and love stories do not die

For that, we have to move away from prescriptive and normative ideas of grieving that promote discourses of “saying goodbye,” “ending relationships” and “moving on”. These are very dangerous ideas for people navigating their way in the face of death and loss. We have to find ways to craft our stories and show up for each other in ways that make us stronger and make our connection with the people who have passed on stronger too.

If you are comfortable with it, I would like you to think of one significant being (human or animal) in your life who has died and who meant a lot to you:

- What words or stories would you use to introduce them?

- What favourite memories would you share that bring a smile to your face or warm your heart?

- What did they appreciate about you that the others might have missed?

- If you saw yourself through their loving eyes, what do you think it meant for them to have you in their life?

- What stories about them would they want to be preserved and told to others?

- What are some of the dreams and hopes you have for yourself that were made possible by your connection to them?

- What sort of things did they teach you about life by their actions or just being who they were?

- What are the ways you have learned to honour their lives through your actions?

- What would it mean for them to know that you carry this legacy forward?

What memories we carry after a person’s death depends on the stories; we are going to craft together. My grandfather, my Dadu, died more than 20 years ago, but he is more alive to me than ever. He was a freedom fighter, a changemaker, a storyteller, and his stories nourished the soil that I stand on today and will continue to do so for generations. As Thich Nhat Hanh, Zen Buddhist teacher and peace activist put it, “All of us are interbeing: we are all connected. When I die, my body will turn to the soil, and that soil will nurture a sapling, and life will continue.”

Acknowledgement to the late Michael White for helping me find a new meaning and language for grief.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05