Opinion Sudhir Patwardhan writes: Vivan Sundaram was an institution builder, and was instrumental in opening up opportunities for younger artists

Collaboration was his default mode. Apart from his own creative work, he was constantly trying to facilitate the work of other artists

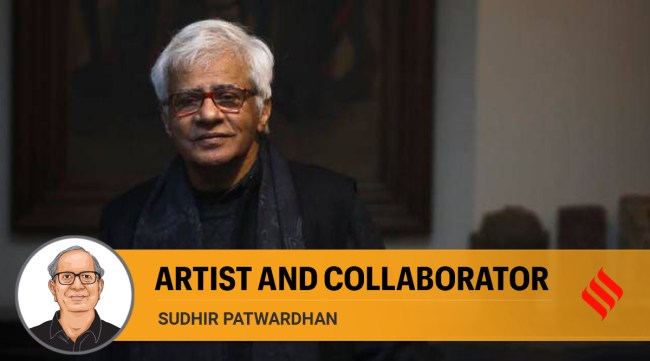

Aged 79, Vivan Sundaram was survived by his wife, art historian and curator Geeta Kapur. (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Aged 79, Vivan Sundaram was survived by his wife, art historian and curator Geeta Kapur. (Express photo by Abhinav Saha) Vivan Sundaram stood steadfast for a committed engagement with the complex mechanisms of society and at the same time the praxes of contemporary art. His passing is a great loss for the art world and more widely, for the cultural landscape of the country.

When I met Vivan for the first time around 1977, he was already a name to reckon with. I had admired his ‘Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie’ paintings, ‘Emergency drawings’ done in response to the 1975 Emergency and his Machu Picchu etchings illustrating Pablo Neruda’s poem, The Heights of Machu Picchu. Our shared commitment to Marxism connected us and we soon became good friends. In 1979, Nalini Malani, Vivan and I had a group show in Bhopal. In its small catalogue, he wrote about our subjects and our aim: “Only when we are to explore imaginatively the language of the medium, assert the physicality of the paint itself, will we be able to show what these people and persons stand for and to get their voice heard.” This exhibition and the discussions we had around it extended to Baroda and, joined by Bhupen Khakar, Gulam Momammed Sheikh, Jogen Choudhry, and Geeta Kapur as our intellectual beacon, became the seed from which the 1981 exhibition ‘Place for People’ grew. This exhibition, held in Bombay and Delhi with no institutional support, was an important watershed in the evolution of Indian art and its “social” turn. Without Vivan’s organisational skills and energy this exhibition could never have taken place.

Vivan’s drawings and paintings of the 1970s and 1980s remain a high point of this movement of a socially engaged figurative-narrative painting. Within his oeuvre of the time there also are many intimate and engaged group portraits of friends, indicating that Vivan took his friendships seriously. Vivan loved children and would eagerly be a guardian to a friend’s child. This personal warmth came to him naturally. He was at heart a family man. He could be headstrong and adamant too, of course, and not always easy to agree with. But that is a concession one makes to one on a mission.

Vivan had the advantage of coming from a sophisticated upper class background. He had early exposure to Indian and European culture of a high order. One can get an insight into this distinctive world in Vivan’s two-volume labour of love for his aunt Amrita Sher Gill. Through detailed annotation of her letters and writings a vibrant personal and cultural art history is revealed to us. Association with Vivan helped many of us to get a feel of that culture and way of life that otherwise would have only been dimly perceived. Being in Kasauli was actually a privilege, but never felt like a privilege due to Vivan’s comradely hospitality. (Vivan would spare no effort to make his guests in Kasauli comfortable, and would be acutely anxious if someone did not feel completely at home.)

Vivan was always deeply engaged with all the constituents of the art world. Apart from his own creative work, he was constantly trying to create situations to facilitate the work of other artists. He was instrumental in opening up opportunities for younger artists, many of whom matured through the international art camps that he organised. He transformed his family home in Kasauli into the Kasauli Art Centre and two or three generations of artists have benefited from the multi-disciplinary camps held there. In this sense, he was an institution builder. He was, however, conscious of the need to keep the institutional work open and inclusive so that it does not ossify and stifle creativity. Collaboration was his default mode. In the same vein he was at the forefront of demanding improvements and changes in government institutions that were not fulfilling their mandate to the artists.

By the late 1980s Vivan was experimenting with new modes of expression, and in the coming decade, his practice changed dramatically to include large scale installations, objects and boxes, videos, photographs and highly sophisticated digital photography. He was one of the first to experiment with these new media in India, and a forerunner of the 1990s generation of global artists. He resolutely maintained and calibrated his ideological bearings in these changed circumstances.

In the last few years, Vivan’s work returned to the human figure. But it was not the strong and attractive figure of the 1980s. This time it was the injured body, the operated body, his own body. These bold, almost gallant works show how he had approached disfigurement with a sense of fortitude and inquiry. The idea of “inquiry”, in fact, was always crucial in his work: Inquiry into the complex, multi-layered web of relationships that make up society; inquiry into the relationships between persons and between classes; inquiry into our relationship to objects, technology, media, thoughts and systems — systems that grow in complexity and then age and wither and finally pass into history.

The writer is an artist