Opinion What Joseph Nye understood about American ‘soft power’ — and what President Trump doesn’t

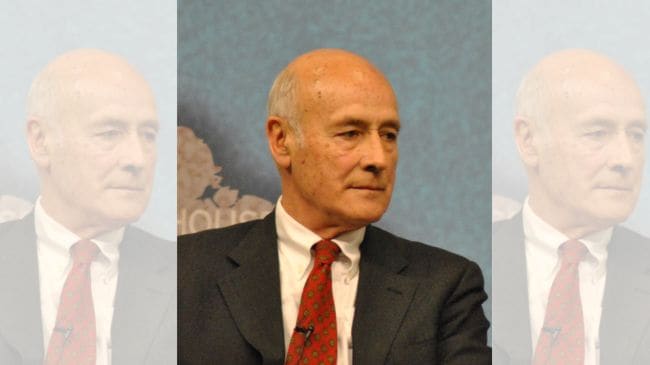

Nye, a former Harvard professor who also served in Carter and Clinton administrations, helped shape the contours of American foreign policy in general and the conception of power in international relations in particular

Joseph Nye's quest to understand the special features that allow governments to exercise influence beyond the size of their economy and the stealth of their militaries led to the birth of “soft power” (Wiki Commons)

Joseph Nye's quest to understand the special features that allow governments to exercise influence beyond the size of their economy and the stealth of their militaries led to the birth of “soft power” (Wiki Commons) Written by Khyati Singh

One of the most celebrated minds in the world of politics, Joseph Nye, died at the age of 88 on May 6. He left behind a legacy that shaped the contours of American foreign policy in general and the conception of power in international relations in particular. Nye developed the concepts of soft power, neoliberalism, complex interdependence, and smart power during his time as a professor at Harvard University. These ideas eroded the perpetual dominance of realist orthodoxy and offered an alternative from a liberal standpoint. His work was not merely theoretical in nature; he actively participated in security roles during the Carter and Clinton administrations.

His quest to understand the special features that allow governments to exercise influence beyond the size of their economy and the stealth of their militaries led to the birth of “soft power”, both as a category and a concept. The inception of this idea cleared space for new vocabulary in a field obsessed with hard-power elements. He argued that in a globalised world, where information is constantly available at the click of a button, depending on hard elements alone is insufficient. Therefore, the burden must be shouldered by nonconventional elements such as pop culture, technological advancements, societal values, and educational outreach to achieve objectives that had always been beyond the reach of military force.

Nye’s ideas garnered salience during the decline of the USSR as events were studied beyond the given literature. The fall of the Berlin Wall was understood in light of ideological victory and not hard-power achievement. American values were able to delegitimise the Soviet regime in numerous ways and offer an alternative.

However, Nye was never in opposition to hard power. For him, these aspects are complementary, and their best use in combination is deemed “smart power”, a term he coined later. Striking the best balance between soft power and hard power is important for realising crucial foreign policy objectives. Therefore, the US victory in the Cold War can be read as having resulted from both hard power and soft power. While the idea of soft power lived on for decades and became a yardstick for countries across the globe to evaluate their stature, it saw a defeat at home with the ascendance of Donald Trump — who has shown absolute disregard for the concept — as the President of the United States.

Nye opined that the Trump administration had set the ball rolling for the decline of American soft power, and he was not alone in this. The first big blow came with the first Trump administration and its emphasis on “America First”, which for many was read as “America alone”, despite the efforts of then National Security Advisor H R McMaster to convince people otherwise. During his second term, Trump has hit several nerves with his remarks on taking over Greenland and the Panama Canal, suspending USAID, and withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement and the WHO. These agencies had acted as bulwarks of American soft power, which thus suffered a blow.

The question that follows immediately is how large the gap left by the retreat of American soft power is and who has the potential and will to fill it. The most recent example is the minimal presence of USAID during the earthquake in Myanmar, which was instantly identified as an opportunity by its rival, China, while India also staked a claim. This directs us back to the understanding that soft power is an essential tool for states pursuing international dominance and great power status. Trump has failed to realise that soft power involves less cost but is a force multiplier.

In FY2024, USAID accounted for 0.3 per cent of a $6.8-trillion federal budget, a minuscule figure in comparison to defence expenditure. However, a close inspection reveals the gains that an insignificant amount of soft power expenditure provides to the US. It validates the US hegemonic position and upholds the liberal world order. It allows the US to market its values of democracy and economic freedom at a time when it faces fierce competition on these fronts from powers such as China and Russia. Furthermore, it clothes the use of US hard power in the garb of promoting democracy.

Similarly, an oft-unattended source of soft power is civil society. While the Trump administration has been accused of degrading American soft power, civil society and corporations are considered alternative vectors. Despite opposition to the US state, people around the globe still believe and invest in the idea of the “American dream”. That ethos can continue to spread and remain intact with the help of soft power commitments.

However, with the constant erosion of soft power under the Trump administration, it is unlikely that the US will return to its original position, especially in the current volatile global context, with nationalism and protectionism pushing back against globalisation. States are increasingly looking inwards, opting for indigenisation and self-reliance. Amidst these concerns, it is fatal for the “superpower” position of the US to let go of the soft power template.

Soft power, and in essence smart power, cemented America’s position as a benign hegemon for decades, with a decent level of acceptance among states in the international order. With Trump’s harsh tactics and blunt attack on this aspect, the legitimacy of American hegemony will slowly start to fade. It will then take another Nye to reconfigure America’s “soft” image, but there may not be many takers by that point. Its position may slowly fall into the laps of smart movers such as India and China.

The writer is a research analyst at the Centre for North America & Strategic Technologies, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses