Opinion Why India went nuclear 25 years ago

At a time when nuclear sabre-rattling is becoming more pronounced globally, India's commitment to pristine deterrence and nuclear restraint should remain resolute

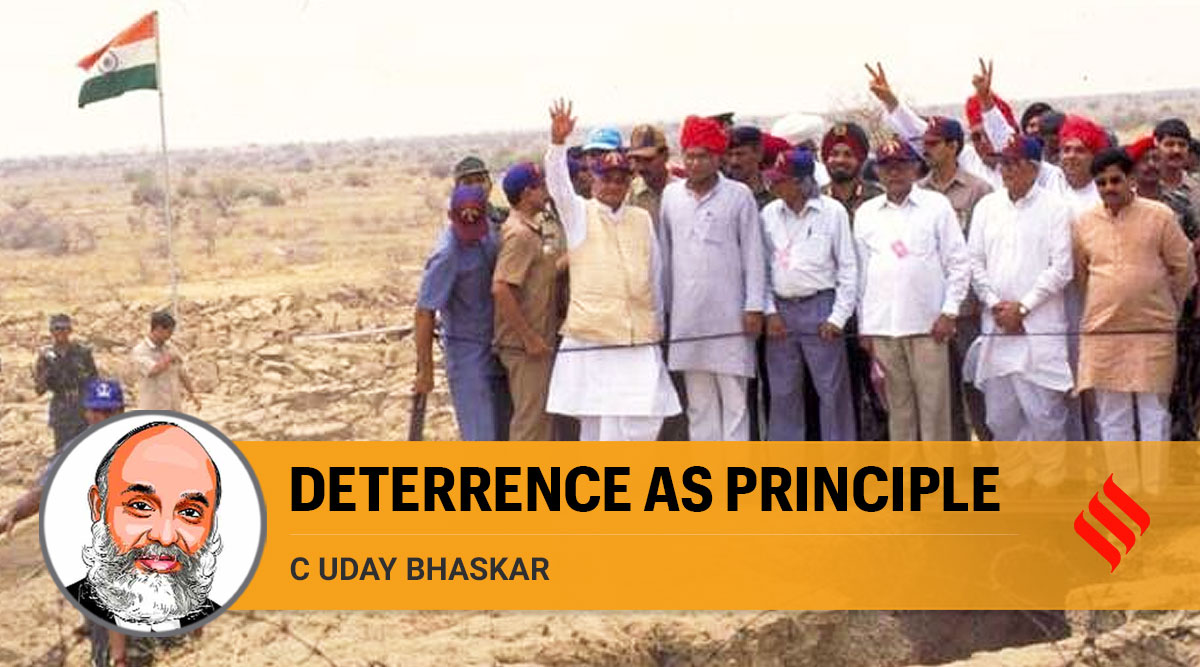

PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the nuclear test site in Pokhran in 1998. (Express Archives)

PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the nuclear test site in Pokhran in 1998. (Express Archives)

India, with then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the helm, declared itself a nuclear weapon state on May 11, 1998, by carrying out a series of three nuclear detonations. These included a 45 KT (kiloton) thermonuclear device, a 15 KT fission device and a 0.2 sub KT device.

A second test followed two days later and having attained the requisite degree of techno-strategic capability, India announced a self-imposed moratorium on further testing. The 25th anniversary of the Shakti tests is an opportune moment to review the complex and contentious nuclear issue at multiple levels: For India, the southern Asian region and the larger global strategic framework.

The Indian nuclear tests took the world by surprise. The US, robustly supported by China, led the charge in denouncing Delhi for refusing to be tethered as a non-nuclear weapon state under the strictures of the NPT (Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty), to which protocol India remains a non-signatory.

The US and most of its allies imposed sanctions on India. There was disparaging conjecture and dire conclusions were arrived at. The trigger for the Vajpayee government to close the nuclear option (that had been kept in suspended animation since the peaceful nuclear explosion of May 1974) in favour of acquiring the weapon was deemed to be “prestige” and a desperate need to be part of the cloistered five-member nuclear club. South Asia was described as the “most dangerous” place in the world and opprobrium was heaped on India.

In retrospect, the prestige argument with respect to India was invalid and devious, for it deliberately obfuscated the strategic and security imperatives that compelled Delhi to act in the manner it did — namely to assuage a deep-seated nuclear insecurity. The facts are irrefutable but in the late 1980s, the US security establishment and the vast ecosystem of American academics and think-tanks invested in a red-herring strategy (that India does not need nuclear weapons for its security) to retain the sanctity of the nuclear club.

China had acquired its nuclear weapon in October 1964 to address Beijing’s own insecurity in relation to the US and the former USSR. But a nuclear China only served to exacerbate India’s post 1962 trauma vis-a-vis its larger neighbour. Soon thereafter, in the mid 1960s, China and Pakistan entered into an opaque strategic partnership focused on nuclear weapons to advance their shared security interests that were inimical to India.

Then Pakistan Foreign Minister (later Prime Minister) Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto played a major role in this furtive operation, wherein Pakistani scientists who had unfettered access to Western nuclear technology shared their purloined designs and blueprints with their Chinese counterparts. Beijing benefited considerably from this transfer of nuclear know-how, for China had strained relations with both the US and USSR at the time. Disgraced Pakistani nuclear scientist A Q Khan and his secret network were the tip of the clandestine iceberg and the Bhutto dream of Pakistan acquiring nuclear weapons even if it “meant eating grass” was soon realised.

Experts maintain that Pakistan acquired the nuclear weapon in the late 1980s courtesy China, which enabled a secret test to validate the warhead design in Lop Nor in May 1990. This Sino-Pak cooperation was being monitored by the US but it chose to keep the matter under wraps and a May 1990 India-Pakistan nuclear crisis narrative was fabricated to add to the red herring strategy.

However, the Indian security establishment had to contend with a stark reality that both its neighbours had the nuclear weapon and that the asymmetry had to be redressed. This was the trapeze that was skillfully managed in the transition from PM Rajiv Gandhi to PM Vajpayee, which enabled May 11, 1998.

In the last 25 years, India has honed its WMD (weapons of mass destruction) capability with improved levels of credibility and has retained its commitment to the NFU (no first use) doctrine. This stems from the conviction that the nuclear weapon has a single purpose — the core mission — to deter the use of a similar capability. This is pristine deterrence and in keeping with its pacifist DNA and strategic culture, the Indian political leadership arrived at a level of sufficiency apropos the quality and quantity of the nuclear arsenal. In essence, the nuclear weapon was not envisioned as a military weapon (the counterforce strategy adopted by the US and USSR in the Cold War) but to caution the potential adversary not to embark on a Hiroshima — for the Indian retaliation would inflict catastrophic damage. Given the proximity of the three southern Asian nuclear powers, apocalypse would engulf the region.

Critics of the NFU advocate that India should go down the counterforce path and acquire tactical nuclear weapons but this is a slippery slope. Tactical in relation to the nuclear weapon is an oxymoron and a rational cost-benefit analysis would indicate that the current nuclear restraint posture is more prudent. Not only for India but for the extended southern Asian region and bringing China and Pakistan to the table will be a test of Indian perspicacity.

Effective deterrence is predicated on the credibility of the entire WMD infrastructure from the prime minister downwards to the strategic forces command and ensuring appropriate efficacy is an onerous task. Currently, some wrinkles such as the role of the Defence Minister in the Indian nuclear ladder need to be reviewed as part of the rewiring of the higher defence management pyramid. The introduction of the CDS (chief of defence staff) is a work in progress and this part of the civil-military command and control needs to be regularly reviewed and simulation exercises conducted.

At a time when nuclear sabre-rattling is becoming more pronounced globally, India’s commitment to pristine deterrence and nuclear restraint should remain resolute.

The writer is director, Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi